If the Republican Party has a secret plan to alienate Hispanic voters, it is doing a bang-up job. These days it seems that the party has greeted the fastest-growing segment of the population by unfurling a massive "Not Welcome" banner. GOP leaders in Arizona and Alabama have passed sweeping crackdowns designed to give undocumented workers the boot. Herman Cain muses publicly about an electrified border fence that would kill trespassers. Michele Bachmann says she wouldn't lift a finger for the children of people in this country illegally because "we don't owe them anything."

And Republican contenders who dare to stray from the hard line tend to get hammered for it. When Rick Perry touted his Texas program offering in-state tuition benefits to some undocumented students, his conservative rivals tore him apart; he has yet to recover. In a debate last week, Newt Gingrich took a gamble in urging a "humane" policy of not kicking out immigrants "if you've been here 25 years and you got three kids and two grandkids, you've been paying taxes and obeying the law." Rival Mitt Romney (who insists he didn't know illegal workers were mowing his lawn) promptly accused Gingrich of peddling "amnesty." Dan Stein, president of the Federation for American Immigration Reform, says that he's offended by Gingrich's "repositioning" and that Òwe stridently disagree it's compassionate to allow people to jump the line and break the law."

All of which makes this a particularly tricky time for the party's leading Latino star—who just happens to be on most Republicans' shortlists for vice president.

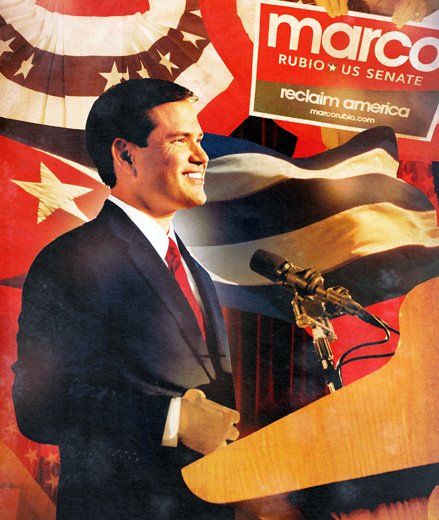

Marco Rubio, the freshman senator from Florida, talks about immigration in a far more sensitive way than many of those who would hire him as their No. 2 in the White House. He does not wander far from the party line. But he doesn't exactly embrace it, either.

"This is not just a theoretical argument," Rubio told me during a recent visit to his Capitol Hill office, emotion creeping into his voice. "You're talking about people's neighbors, people's moms, people's sisters, people's brothers, their loved ones, maybe their spouse or their children. You know kids that have grown up here their entire lives but are undocumented." His dark eyes flash as he imagines the plight of those who cross the border illegally: "If your kids are hungry and hurting and living in a dangerous environment, there's very little you won't do to help them."

Yet Rubio's passion hasn't caused him to break with the conservative GOP establishment. He straddles the border between living and limiting the American Dream.

One year after his upset victory, Rubio is constantly touted as a surefire asset for the 2012 ticket. He is, without question, a running mate out of central casting: young, fresh-faced, Hispanic, and aggressively conservative, with the potential to deliver a crucial swing state. "He's a future superstar—a dynamic, attractive candidate with a beautiful family who gives you potential inroads in the Hispanic community," says veteran GOP strategist Ed Rollins.

Rubio insists he's not interested in a VP bid, saying the party can't solve its Hispanic problem just by drafting "a person whose name ends in a vowel." His team welcomes the veep chatter because it gives him a larger megaphone, but wants to preserve his option of running for president in 2016—which Rubio would forfeit if his ticket beat President Obama this time around.

How badly does the GOP need him on the ticket? Obama, who captured two thirds of the Latino vote in 2008, has disappointed Hispanic leaders—giving the Republicans an opening to make gains. But today's GOP has drifted far from the immigrant-friendly platform of George W. Bush, who pushed for a path to citizenship for the nation's 12 million illegals. Since then, Arizona adopted the nation's most draconian law last year, giving police authority to detain anyone suspected of being in the country illegally. An Alabama law that took effect in November appears to require proof of citizenship or legal residency even for dog licenses and flu shots. Obama's Justice Department has sued both states, as well as South Carolina over a similar measure. And there are signs of a backlash, with Arizona voters in November recalling the law's chief Republican sponsor.

To Rubio's frustration, he has been drawn into the cauldron of immigration politics. "Some people have ridiculously high expectations about his ability to help the party with Latino voters," an adviser says.

Still, that hasn't dimmed the party's enthusiasm for him. "He has the unique gift of communicating in both languages—he's better in Spanish than in English," says Carlos Lopez-Cantera, majority leader of the Florida House. ÒHe's able to put complex, confusing issues into a very digestible format. He's the real deal." And Miami radio host Ninoska Pérez-Castellón says it hasn't gone to his head: "He's still the same Marco, a very humble person."

That may be true, but it's unclear how effective Rubio would be at rallying Hispanics nationally; he is a minority within a minority. "Just because he's a Cuban-American from Miami doesn't mean Mexican-American hotel workers in Las Vegas are going to vote for him," says Roberto Suro, former head of the Pew Hispanic Center. People of Cuban origin represent just 4 percent of America's Hispanic population, compared with 63 percent for Mexicans.

Rubio is still growing accustomed to his newfound stardom. Days after he overcame a 30-point deficit and drove former governor Charlie Crist out of the GOP in winning the election, he phoned an adviser with excitement in his voice. "Guess who called me?" he said. "The president." It was a routine ritual of congratulation, but a touching one for the son of a bartender and a maid.

Arriving in Washington on a wave of Tea Party support, he immediately lowered his profile, not wanting to squander his sudden fame. But Rubio, whose signature campaign issue was runaway federal spending, tossed out the timetable to wade into the capital's debt-ceiling negotiations.

Rubio's halo was tarnished a bit when The Washington Post reported in October that his parents had legally emigrated from Cuba not when Fidel Castro seized power but in 1956, some two and a half years earlier—a less dramatic rendering than that in his Senate biography or his self-description as the "son of exiles." That was an inadvertent mistake, Rubio says now, but "I didn't benefit from getting the date wrong. My parents were still exiles ... The bottom line is they can't go back because of Castro." The left, he says, is trying to "turn it into Watergate."

At 40, Rubio is young enough to declare that he doesn't want to be "intoxicated" by Washington and savvy enough to sense it may be too soon for him to abandon the Senate. "This place is full of former rising stars that were once the next big thing," he says. "I think that stuff is fleeting."

Whatever Rubio's short-term future, the Hispanic community, which has surged by 43 percent in the past decade, will have a major impact on the White House race, especially in such up-for-grabs states as Arizona, Colorado, and Florida.

With Obama failing to aggressively pursue his campaign promise of immigration reform—and ramping up deportations instead—a recent Univision poll shows that only 1 in 3 Latinos strongly approves of the president. And there were doubts from the start of the 2008 contest, when Hillary Clinton trounced Obama among Hispanics. "It wasn't love at first sight," Suro says.

Despite the disaffection, three years of tough Republican talk has taken its toll. The same poll gives Obama a 2-to-1 lead over Romney, Perry, and Cain among Latinos.

Rubio, for his part, has pushed back against excessive rhetoric from conservatives in the past, calling former GOP congressman Tom Tancredo a "clown" for referring to Miami as a "Third World country." "It's important that the Republican Party be for something," says Rubio, and not just campaign as Òthe anti-illegal-immigration party."

But Rubio himself has made a sharp right turn in abandoning his earlier support for tuition breaks for children of illegal immigrants. "He changed his mind on that because he was so focused on pandering to the Tea Party that he abandoned some core principles," says Debbie Wasserman Schultz, the Florida congresswoman who chairs the Democratic National Committee. She calls Rubio "talented and smart" but "out of step with the Hispanic community. On immigration he's got views that are just offensive."

Rubio's response? A delicate high-wire act. "It's not my position that has changed. The country has changed," he says, adding that Americans are feeling less generous toward immigrants in tough economic times. After a recent visit to El Paso, he credits Obama with "a good start" on tightening border security. He leaves the door ajar to doing something to help "high-achieving" students brought to the U.S. through no fault of their own, but then pivots to argue that "people are taking advantage of America's generosity." For a Republican with a national profile, it's a very thin tightrope indeed.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.