Updated | In the thousands of hours Boye Brogeland has spent playing bridge, he had never before proffered such a bold declaration—not even an artificial two clubs bid. Seated at home in the picturesque harbor village of Flekkefjord, Norway, in late August, he gazed at his computer screen, at the words he had written and was about to post online: "If you have a cheating pair on your team.…"

But before doing so, Brogeland alerted the authorities. His accusation, he knew, would reverberate north and south, east and west across the global coordinates of high-stakes contract bridge. It could end the careers of the reigning European champions, Lotan Fisher and Ron Schwartz, the former known as "the wonder boy of Israeli bridge"; it would also likely mean a terminus to their six-figure income, their Bali-to-Biarritz jetsetting lifestyles.

Brogeland also knew that the men whose livelihoods he was about to kill had powerful and extremely wealthy friends, men whose very behavior at the square table betrayed malevolent intentions. "I phoned the Norwegian police," says Brogeland, a professional bridge player who is ranked 64th by the World Bridge Federation (WBF). "They told me, 'When you blow the whistle, do not be at your home address.'"

The Sheriff and the Anonymous Astronomer

On September 26, the Bermuda Bowl, a biennial international event that happens to be the most prestigious tournament in all of bridge, commenced in Chennai, India. Of the 22 nations that qualified to play in the fortnight-long championship, three have dropped out in the past month: Israel, which boasts the tandem of Fisher and Schwartz; Monaco, whose duo of Fulvio Fantoni and Claudio Nunes are the No. 1- and No. 2-ranked players in the world, respectively; and, most recently, Germany.

The absences of Fisher-Schwartz and Fantoni-Nunes at the Bermuda Bowl are due directly to the punctilious investigative efforts of Brogeland. In fact, all four men are facing lifetime bans from competitive bridge. He may only be the world's 64th-ranked player, but there is no more formidable opponent in bridge than Brogeland (Germany withdrew after its top pair, in the aftermath of the investigations, pre-emptively confessed to cheating).

"Boye is the sheriff who rode into town," marvels Bob Hamman, a Texan who has won 10 Bermuda Bowls and is to contract bridge what Doyle Brunson is to Texas Hold 'Em. "He's Judge Roy Bean. He's the man of the year."

Imagine, if you will, NFL fans, a crusader who took on the most successful teams in his chosen sport and who just happened to have facts on his side. Who conducted his investigation not by spending millions of dollars on private investigators, but rather via crowdsourcing YouTube videos and enlisting the help of willing volunteers from as far away as Australia, from legends of the game (such as Hamman) to an anonymous astronomer from the Netherlands.

Now imagine that none of this was undertaken for personal gain or image safeguarding—was in fact initiated at both fiscal and professional expense—and that the provocateur, Brogeland, demanded that any Master Points he had "won" (his quotations) as an erstwhile teammate of Fisher and Schwartz be vacated. And that he continued unbowed after one of the men he accused, Fisher, posted these words on Facebook: "Jealousy made you sick. Get ready for a meeting with the devil."

"My only motivation is to try to clean up the game and do the right thing," says Brogeland, whose grandparents taught him to play bridge when he was 8 years old. "Don't worry about the consequences. This is what my mother would do. This is what my father would do. I hope this is what my children would do."

"Boye [has] made it his personal campaign to clean up the game," says Jeff Meckstroth, an American who is ranked eighth in the world by the WBF and has won the Bermuda Bowl five times.

This is the story of a bridgegate that is altogether unlike the one involving a certain New Jersey governor and the town of Fort Lee (that is, except for the shared traits of skulduggery, whistleblowing and personal threats). This is the story of, as Brogeland puts it, "A rebellion staged by the bridge players themselves, via the Internet, to save the game."

Old Dogs With Nasty Habits

"Now how do you wanna play? Honest?"—Chico Marx, preparing to deal a hand of bridge in Animal Crackers (1935)

In 1925, the railroad tycoon and Gatsby-esque sportsman Harold Stirling Vanderbilt was sailing aboard his yacht from Los Angeles to New York via the Panama Canal. During the voyage, Vanderbilt decided to spruce up the game of auction bridge, which itself had evolved from the English game of whist. "Vanderbilt came up with a system in which a duo could earn extra points based on how ambitious their bid was," says Dave Anderson, a retired newspaperman and avid bridge player who lives in Florida. "He invented contract bridge."

It took only 10 years, an interim during which bridge tournaments blossomed into international events that were often front-page news in The New York Times, before the Marx Brothers lampooned the game's primary flaw. "Bridge is the easiest game in the world at which to cheat," says Kit Woolsey, a highly accomplished bridge and backgammon player who has written extensively on both games, "because you've got a partner and you can signal."

If you are not already familiar with the basic concepts of bridge, fear not: You are not about to learn them here (although, here is a brief Bridge for Dummies primer). "It takes at least 12 hours of study before you should even sit down at a table," says Chris Willenken, a New York–based pro who is currently providing beginner's lessons at a hedge fund in 10 two-hour increments. "There are quadrillions of possible hands that you can hold."

The American Contract Bridge League (ACBL), the governing body of North American bridge, counts 168,000 members, and yes, an overwhelming majority of them are either your grandmother or have AOL email accounts. "Our typical new enrollee is a 65-year-old woman, and the average age of our members is 71," sighs ACBL spokeswoman Darbi Padbury. (Ironically, not a single woman ranks in the Top 100.)

And yet the game continues to attract some of the world's most innovative (and wealthy) men. Warren Buffett and Bill Gates not only play but regularly compete as partners. No Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting is complete without a daily 1 p.m. bridge game that includes an appearance by Hamman, which is akin to Dan Marino showing up at your touch football game. Just last month, Facebook, a company whose founder's parents are avid players, applied with the ACBL to have a registered bridge game on its Menlo Park, California, campus.

Jimmy Cayne, the former chief executive of Bear Stearns, is obsessed with bridge. As the investment bank was sliding into insolvency in 2007 and 2008, Cayne, now 81, was incommunicado as staffers attempted to reach him on more than one occasion: sealed off from the rest of civilization at a bridge tournament. Bear Stearns, in part due to Cayne's bridge-addled negligence, went under. "I've known Jimmy Cayne since woolly mammoths roamed the plains," says Hamman. "He's an old dog, and old dogs can acquire some bad habits."

And even worse players, but more on that later.

The Dreaded German Doctors

To oversimplify the game of bridge: Two partners sit directly across a table from each other (north and south) and attempt to win more tricks (i.e., hands) than their opponents (east and west). The difficulty lies in not knowing what cards your partner is holding or even what his or her long suit (the most cards of one suit among the 13 cards he or she has been dealt) might be. If, on the other hand (pun intended), a partner were to be armed with that knowledge...

"That would be akin to knowing what the opposing team's third base coach was signaling," says Willenken, an irrepressibly logical creature who gives out his age as "39 and seven-eighths."

It was Mae West who famously compared good bridge to good sex: "You better have a good partner, or you better have a good hand." Or you can cheat.

At the 1965 Bermuda Bowl in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the British duo of Terence Reese and Boris Schapiro were disqualified after a two-time former champion, B. Jay Becker, observed that they held their cards with a certain number of fingers resting on the back during bidding to indicate the length of their heart suit. Within 10 years, to discourage this and other visual signaling, tables at major tournaments were fitted with a screen that ran diagonally across so that partners could no longer see each other.

Hence, at the 1975 Bermuda Bowl a pair of Italians, Gianfranco Facchini and Sergio Zucchelli, communicated by playing footsie under the table. In the aftermath of their mischief, boards now run beneath the table.

Thus, a pattern emerges: Each transgression obliges a new means of deterrent, which in turn inspires a more creative manner of cheating. The result, at the elite levels of bridge, is the difference between an ordinary conversation and Clarice Starling interviewing Hannibal Lecter. "I truly believe most bridge players are good guys, full of integrity," says Meckstroth, who has played with the same bridge partner, Eric Rodwell, for 41 years. "But there is a minute percentage at the highest levels that compel us to be vigilant."

Two years ago, at the d'Orsi World Senior Bowl in Bali, Michael Elinescu and Entscho Wladow, both of Germany, were found guilty of using a system of coughs to communicate to each other their hands. Both men, who have been banned from playing together for life, are physicians. "Historically speaking, the phrase German doctors has implied far worse [deeds]," sniffed The Guardian, "but still, it was the world championship finals."

Hamman, who has won more major tournaments than any American and who has probably lost just as many to cheaters, is somehow able to remain sanguine. "It's human nature. It's the way we're engineered," he says. "I played against the famed Italian Blue team. They won 17 of 19 world championships at one point, and the fact is they cheated. Everyone knows that. There's problems in everything you do, and it's called life."

Cracking the Cheat Code

Mid-August. Chicago. The prestigious Spingold championships, which draws an international field of elite players, is being staged at the Hilton. During a quarterfinal match, Boye Brogeland and his partner, Espen Lindqvist, lose by one point to the Israeli duo of Fisher and Schwartz. "I was gutted," says Brogeland. "Bridge is such a logical game, and they were making such nonlogical actions. Nonlogical action after nonlogical action, and it was a success every time.

"Afterward, I met Jimmy Cayne at the bar," Brogeland says. "Jimmy had played really well. I told him, 'You need to get rid of these guys.'"

If something in that quote does not quite add up for you, here is the final reveal about elite-level bridge: While each game features two-player pairs, a registered team is composed of three pairs, or six players overall. At the world-class levels, that sextet is usually composed of five handsomely rewarded players and one sponsor, a very wealthy bridge aficionado who plays the minimum number of hands in order to be considered part of the team.

"It is the only way possible to have professional players is to have these sponsors playing," concedes Brogeland. "They don't want to watch, they want to play. And there wouldn't be enough interest in bridge otherwise to have professionals."

"Yes, bridge is played by affluent people," says Padbury. "And there's lots of money involved. But we're not giving it out [as prize money]."

Hamman, who was part of the very first sponsored American team, the legendary (relative to the world of bridge) Dallas Aces, says the top players earn anywhere from $200,000 to $500,000. "You have a sponsor who has accumulated quite a bit of money, and he's a pretty good bridge player," says Hamman. "He wants the team he wants, and he can afford to procure it."

To the outsider, it sounds like an NBA owner suiting up, playing one quarter with the Spurs, and then claiming he and Tim Duncan won the NBA title together. Bridge pros are not so, well, cynical. "They get to call themselves champions," says Woolsey, "and why shouldn't they?"

In theory, the dynamic is above reproach. In practice, however, it incentivizes players of a certain moral turpitude to cheat. "There is more of an incentive than you realize," says Padbury.

And so Brogeland, who had spent the previous two years as a teammate of Fisher's and Schwartz's, had seen them jump to a more lucrative offer to play for Cayne. And then he'd lost to them under what he considered bizarre circumstances.

In fact, Brogeland and Lindqvist had actually won their match by one point. But bridge has an appeals process, and after the appeal Fisher and Schwartz were awarded a one-point victory. "It was pathetic behavior," says Meckstroth, who observed it all. "Fisher was pumping his fists and yelling, 'Yes! Yes! Yes!' It was a dubious ruling."

When Brogeland had been teammates with Fisher and Schwartz back in 2014, he had once quizzed them about a dubious move that proved advantageous during a match. "Why did you lead a club?" he had asked Schwartz, who replied, "I have to lead my partner's suit."

There was no way, at that point in the hand, for Schwartz to have known what Fisher's long suit would have been. So how did he know he had to go with clubs?

Brogeland returned home to Flekkefjord, where he and his wife, Tonje, undertook the tedious yet engrossing task of watching Fisher and Schwartz win the previous year's European championships via YouTube. (The ACBL, which oversaw the Spingold tournament, does not post its videos online.) "My average hours of sleep for an entire week was three hours," he says. "My adrenaline was so pumped up."

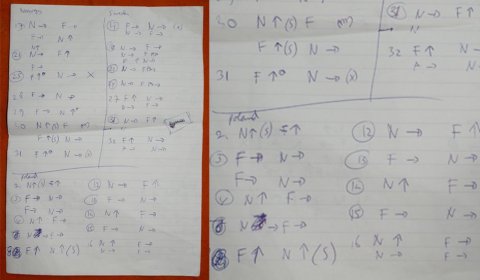

Thanks to a system called VuGraphs, bridge fans and watchdogs are able to see a chart of the complete hands all four players are holding during any one hand (after the match has been played). If an experienced student of the game matches those charts to the videos of the hands, he or she might eventually find a recurring signal being passed between partners, one that correlates to a specific play. "Bridge is a relentlessly logical game," says Willenken, one of a coterie of top-level players whom Brogeland enlisted to help him uncover Fisher's and Schwartz's chicanery. "There's a three-step process to cracking the code: Look at actions that are illogical; find a disproportionate amount of winning hands preceded by illogical actions; and analyze what is going on in those hands."

In the dying days of August, after he had publicly accused Fisher and Schwartz of cheating on a site called BridgeWinners.com without offering any explicit evidence, Brogeland received a threatening letter from their attorney. It accused him of defamation and read, in part, "my clients will agree to compensation in the sum of one million dollars…a small part of the damages and mental anguish that has been caused."

It was then that a Swedish player whose help Brogeland had enlisted, Per-Ola Cullin, cracked the code. Cullin, rated 67th by the WBF, noticed that the board on which players pass their bids—a trap door at the bottom of the diagonal screen opens enough for players to perform integral rites of play—was placed at certain spots on the table to indicate preferences for an opening lead (e.g., if Fisher or Schwartz wanted his partner to lead with diamonds, the board is placed on the middle of the table).

"Per-Ola is the one who cracked the code," says Brogeland. "This has been a rebellion staged by the bridge players themselves who wish to clean up the game, and we have used the Internet to wage our battle."

By September 5, Israel had withdrawn from the Bermuda Bowl, even though the WBF had yet to officially sanction the team of Fisher and Schwartz. (And still has not.)

On September 6, Maaijke Mevius, a 43-year-old married mother of two who lives in Groningen, Holland, decided to send an email to Brogeland. Mevius, a recreational bridge player, had been keeping track of the Fisher-Schwartz scandal, and had noted that in the 2014 European Championship finals, their opponents had been Fulvio Fantoni and Claudio Nunes.

The next day, Cayne, who has not been accused of any wrongdoing in this affaird, posted this on bridgewinner.com: "As captain of my 2015 Spingold team, I make this statement with heavy heart. In the last few weeks I have been made aware of charges leveled against Lotan Fisher and Ron Schwartz, a pair on my team. The most recent published hands lead me to conclude that Fisher-Schwartz may not continue to play on my team unless they are cleared of all charges which might be filed against them. I am completely on board forfeiting my title, masterpoints, and seeding points for the 2015 Spingold if the ACBL will allow me to do so."

Mevius wasn't done. If Fisher and Schwartz had communicated via signals, she wondered, why not peruse the same videos and see if Fantoni and Nunes had also done so? "I am a researcher by profession," says Mevius, a physicist whose field is astronomy. "I'm interested in how the world works. Also, I'm a problem-solver. Playing bridge is all about problem-solving."

After analyzing hours of videos and keeping meticulous notes, Mevius discovered a pattern. She told her husband, who advised her to send an email to Brogeland, whom she has never met. "I think this may be a code," Mevius wrote, "but I don't have the expertise to judge it. The vertical card is either an ace, a king, or a queen."

Within minutes, Brogeland replied, "Wow, you may have broken the code."

Elite-level bridge has three top-tier tournaments, none of which are held annually: the Bermuda Bowl (odd-numbered years), the Olympiad (quadrennially in Olympic years) and the World Open Pairs (quadrennially in non-Olympic, even-numbered years). To win all three is to capture the "triple crown of bridge," and only 10 men have ever done so. Two of them are Hamman and Meckstroth, who completed the trifecta as teammates in 1988.

Only two men have captured the triple crown in the past 25 years: Fantoni and Nunes, a fact that rankles not a few veterans. "Fantoni was obviously a phony in my opinion," says Meckstroth. And Nunes? "I just thought he was a prick," says Meckstroth.

After Mevius sent her email to Brogeland, he forwarded the information to some of the top players he knew, such as Meckstroth, Willenken, Woolsey and others, for verification. Eventually, Ishmael Del'Monte, an Australian player, provided it.

"Ishmael wrote me back 12 hours later and verified it," beams Brogeland.

Meckstroth was driving from the ACBL headquarters in Horn Lake, Mississippi, to his home in Clearwater, Florida, on the morning of September 10 when he received a phone call from an excited Del'Monte. "Ish had been up 36 hours straight looking at video of Fantoni and Nunes," Meckstroth says. "I told him to get some sleep, that I would do the job of communicating it."

Meckstroth phoned Woolsey, who by the next morning posted a story on BridgeWinners.com, breaking the news to the world that the two most successful bridge players of the past quarter-century are cheats. Woolsey's story more closely resembled lab analysis, with exhaustive and meticulous details as to the precise moments in hands during the 2014 European Championships when Fantoni and Nunes had thrown down their cards in a certain manner that corresponded to particular hands. Within a day or so, the post had garnered 1,173 comments.

"The evidence that Fantoni and Nunes threw their cards down either vertically or horizontally corresponding to what types of cards they held is indisputable," says Willenken. "The only thing that's in question is an interpretation of what that means. But the odds of it not being a system of cheating are infinitesimal."

Fantoni and Nunes have said little publicly about their predicament. On what claims to be Fantoni's official website, this message was posted in mid-September: "We will not comment on allegations at this time, reserving our right to reply in a more appropriate setting."

Meanwhile, Brogeland received a veiled threat. A mutual acquaintance passed on a message, reportedly from Fantoni and Nunes: "Tell your friend Boye that we have a wheelchair that will fit him."

"This one's the biggest cheating scandal in the history of bridge," says Woolsey. "Fantoni and Nunes were the top players; they were winning the most championships."

Dror Arad-Ayalon, a Tel Aviv-based lawyer representing Fisher and Schwartz, dispatched a letter to Brogeland accusing him of "offensive defamation which is not supported by one iota of truth." On September 17, Arad-Ayalon told CNBC that once an Israel Bridge Federation's investigation into the charges against his clients was resolved, the players intend to sue Brogeland for defamation.

For Hamman, who owns a sports promotional company that recently won a $12 million appeal in a long-standing court battle with another famous cheater, cyclist Lance Armstrong, this is just another example of human nature. "Oh, it's a bumper crop of cheaters this year," he says with a grin. "The harvest is going to be good."

In the wake of Brogeland's challenge of Israel and Monaco's top teams, Germany's top pair, Alexander Smirnov and Josef Piekarek, have confessed to cheating. That makes three of Europe's six qualifying teams out of the Bermuda Bowl. "People have been telling me, 'If you can just take another nation or two down, then Norway can go,'" says Brogeland, who has accrued phone bills in the thousands of dollars the past month. "That's never been my motivation. I love bridge."

In all the lost hours of remaining in seclusion and of painstakingly poring over footage of past bridge matches, Brogeland did find the time to send a reply to Fisher's and Schwartz's attorneys. He wrote, "Please sue me."

This story has been updated to include posted statements from Jimmy Cayne and Fulvio Fantoni, as well as a letter sent by the laywer for Fisher and Ron Schwartz, and comments he made to CNBC.

About the writer

John Walters is a writer and author, primarily of sports. He worked at Sports Illustrated for 15 years, and also ... Read more