Some narratives grow so large and amass such power that they become bulletproof. Such is the case with the conventional wisdom regarding cable TV's big man on campus, HBO. The first is that the network hasn't had a real series hit since The Sopranos ended in 2007. That isn't exactly true—True Blood boasts boffo ratings and has won an evangelical following, but it certainly lacks the critical acclaim or prestige that The Sopranos brought with it. The other fish story is that HBO has been in a four-year shame spiral since allowing Emmy magnet Mad Men, the brainchild of former Sopranos writer Matthew Weiner, to slip into the welcome arms of AMC. Though network executives have graciously congratulated their scrappy competitor, HBO's anticipated new series Boardwalk Empire, which is set in Atlantic City during the Prohibition era, is bound to fuel notions of their historical-drama envy. Empire, created by Sopranos alum Terence Winter, seems almost self-conscious in the way it combines the criminal voyeurism of its former flagship with the persnickety period detail of the instant classic that got away. But it's good enough to make quibbling seem like too much trouble. Based on Nelson Johnson's obsessively researched book, Empire begins in early 1920 as Prohibition is just taking effect, at which point revelers spill into the streets, burying a bottle-shaped effigy of John Barleycorn, and, naturally, getting properly soused. Steve Buscemi stars as Enoch "Nucky" Thompson (drawn from the real-life racketeer Nucky Johnson), the czar of Atlantic City, a political boss as powerful as he is avaricious. As the townsfolk are playing dirges for their beloved sauce, Nucky is positioning himself and his cronies for a windfall when they control all the bootlegged liquor. It's the cusp of an age of unparalleled lawlessness and vice, and Nucky is three knee-deep steps ahead of it.

If the cultural relics of Mad Men seem shocking in retrospect—the consumption, the sexism, the unapologetic prejudice—Empire renders them quaint by comparison. The world of Boardwalk Empire is far more naughty, shocking, and decadent, and not just because of the latitude premium cable provides. Unlike the 1960s of Mad Men, when the advertising industry is an openly boozy bacchanalia, in Boardwalk Empire's roaring '20s, indulgence is forbidden—fermented fruit. Sexual exploration is in its infancy. A character sheepishly asks his wife for oral sex by reminiscing about his days abroad: "When we were outside Paris, fellas were talking about some gals they met…" Prohibition also led to the mainstreaming of jazz and integrated speakeasies, yet another social taboo being broken decades before the tension came to a head.

Where Mad Men is all about the packaging of desire, Empire is about the suppression of desire, how the more we try to deny ourselves pleasure, the more intense the hunger for it becomes. Johnson's book and its series adaptation aren't alone in wanting to explore the period; there was also last year's The Prohibition Hangover by Garrett Peck, and earlier this year, Daniel Okrent's Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, which documentarian Ken Burns is using as the basis of a film project to be released next year. In other words, Prohibition is so hot right now. In addition to providing history with some of its most delicious villains, the Prohibition experiment is a potent metaphor for our recessionary times: how do we react when the party is over and the sobering reality of our reduced circumstances is staring us in the eye?

Empire is far more sprawling than you'd expect by the title, which suggests a microscopic look at the inner workings of Atlantic City. Like The Wire as a silent film, the show tumbles all over the place, exploring the dynamics of the racket in New York and in Chicago, where a young, cherubic Al Capone is a bartending lackey. Its briskness demonstrates that period accuracy doesn't have to diminish the story. Empire teems with plot. By the end of the pilot (directed by Martin Scorsese, making his series-television debut), a tapestry of absorbing arcs has been sketched out. The pilot's density is almost intimidating, but it's mostly table setting. The pace of subsequent episodes slows—a little, anyway—and allows the story to blossom.

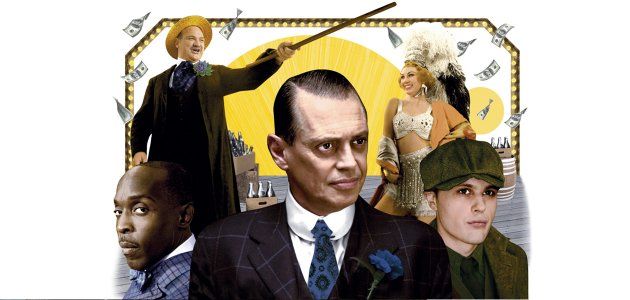

The detail of the era is on glorious display, from Nucky's impeccable wardrobe to the bustling boardwalk, which includes such attractions as a storefront incubator where customers can pay to gawk at premature babies. There is one major—and welcome—departure from historical accuracy. Where series such as The Tudors cast impossibly handsome actors to portray historically homely monarchs, Empire relies on a character actor even more, ahem, "characterlike" than his real-life counterpart. Unlike the hearty, real-life Nucky, Buscemi is slender and squirrelly, with wild eyes and a snaggletoothed smile. His slight frame works to his advantage (and not only because it puts some distance between Nucky and Tony Soprano). Nucky can be ferocious, but when he quells a brewing war between two factions with a brief, quiet negotiation as opposed to force, we get a sense of the power of his intelligence and cunning. The rest of the cast is just as formidable. Michael Pitt plays Jimmy Darmody, Nucky's driver and flunky, whose ambition to rise through the ranks of Nucky's organization quickly congeals into hubris. Pitt has always been reminiscent of an indie it-boy version of Leonardo DiCaprio, but never more than he does here—and under Scorsese's direction, no less. Michael Shannon provides his usual intensity as a Prohibition agent who sniffs out even larger misdeeds in Nucky's organization than a few barrels of basement whisky.

Boardwalk Empire has a good chance of becoming more than the series that restored HBO to its Sopranos-era halcyon days. It could very well be the beginning of a successful campaign to destroy the prestige lines between film and series television once and for all. Landing Scorsese as a director and executive producer on a series is a minor coup and was likely instrumental to attracting Buscemi, Pitt, and Shannon, none of whom has starred in a series. Meanwhile, Michael Mann will be directing Dustin Hoffman and Nick Nolte in Luck, a horse-racing drama from David Milch, while Kathryn Bigelow is directing The Miraculous Year, a behind-the-scenes drama about a Broadway play that will star Susan Sarandon, Frank Langella, and Patti LuPone. Last year the channel dropped the "It's not TV, it's HBO" slogan, and with good reason. After helping to redefine the connotations of television, and on the cusp of doing it again, there's no reason to hide from that word anymore. Empire is further proof that we're living in a golden age of television, and that's reason to party like it's 1919.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.