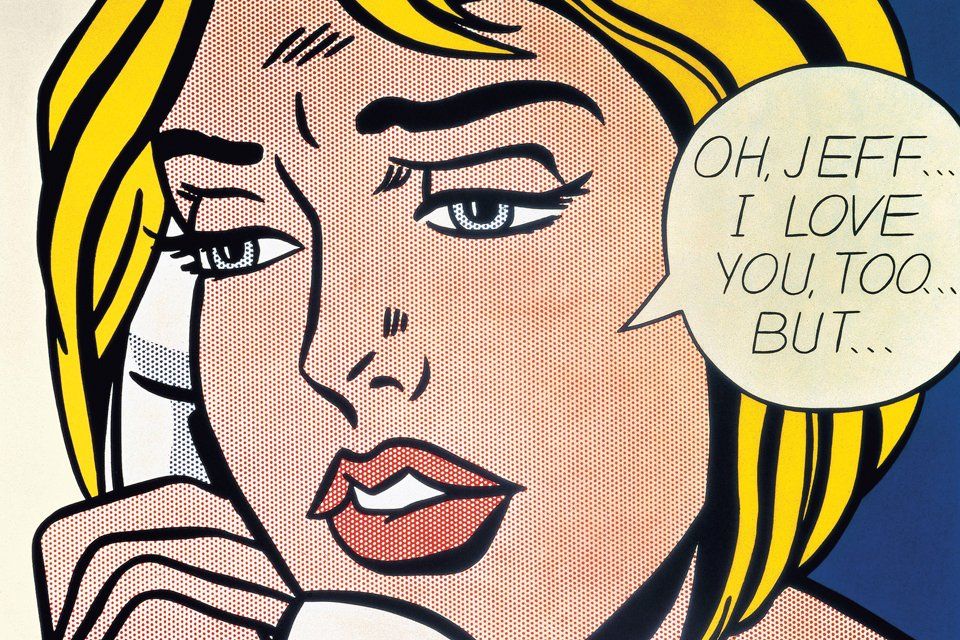

Last week on a New York subway, I glanced at an ad for a local pawn shop. Styled like an enlargement from a comic book, complete with a weepy blonde and speech bubbles and giant dots of color filling up the background, it was a testament to the staying power of Roy Lichtenstein, the great American artist who pioneered such comic-book borrowings more than five decades ago. In 1961, when he launched his series of Marvel-ous and DC-licious paintings, he became a founding figure in pop art. Within a few years, his images had been sucked into the culture at large, where they still re-main lodged—even under the streets of New York.

Lichtenstein died in 1997 at the age of 73. Now, 15 years later, the Art Institute of Chicago is about to open the largest-ever look at his art, taking in everything from his early romance and war imagery to his riffs on art history to his nudes, mirrors, brushstrokes, landscapes, and architectural details. The show is bound to be popular and fun, but its themes can also dig deep.

Lichtenstein, I think, is the first artist to give us a whiff of the Pinterest culture we live in today, where it can be a hot trend to build a Web page entirely from images you've clipped elsewhere on the net—no text need apply. Thanks to the Web, our culture has finally reached that moment, long predicted by scholars, where pre-packaged images yield our most important contact with reality, and the rest of experience then comes filtered through them. Lichtenstein saw it coming. Before him, artists had painted pictures of the world, as it impinged on their eyes and psyches. (The results could range from realism to distortion to expressive abstraction.) Lichtenstein's revolution was to paint only what came at him predigested in the images of others, as ready-mades there for his use. "That's what I meant," Marcel Duchamp is supposed to have said on first seeing Lichtenstein's work.

Some people are shocked at how closely Lichtenstein's comic-book appropriations follow their sources; whole Web pages are devoted to outing this "plagiarism." But Lichtenstein needs to stay close to those sources because he's a realist, out to convey the picture-world we all live in—the way Rembrandt captured Amsterdam's burghers and Hopper portrayed dawn in New York.

In a new book called The First Pop Age, Hal Foster describes Lichtenstein's art as speaking to Homo imago, a new species of "image man" whose touchstones come from mass media. He quotes Lichtenstein: "I don't care what, say, a cup of coffee looks like. I only care how it's drawn, and what, through the additions of various commercial artists, all through the years, it has come to be."

That's why, in so many Lichtensteins, huge swaths of the surface are covered in dots, as though we're looking at cheap printing through a magnifying glass. (Lichtenstein was a middle-class New Yorker who trained in fine art, but a stint as a technical draughtsman in Cleveland taught him the mechanical side of depiction.) Those exaggerated printer's dots appear in Lichtenstein's early comic-book borrowings, where they are at home, as well in his later landscapes and interiors, where they deliberately aren't. But wherever Lichtenstein scatters them, their job is to signal that his art depicts a world of printed images, not of things—because that's the only world that's left for us to live in.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.