By the time the lights went down, a few minutes into the morning of Jan. 24, the Sundance Film Festival crowd was ready for a good scare. For weeks there'd been buzz about a grainy little horror movie called "The Blair Witch Project," by two unknown guys from central Florida who were looking for a distributor. Now, the film industry's elite gatekeepers would get their chance to see, and perhaps buy, for themselves. Executives from Miramax, Fox Searchlight and other distributors waited in the Park City, Utah, snow to get in. "Blair Witch" was in play.

Shot entirely on jumpy handheld cameras, for a budget that would barely buy a new car, the movie offered a grabby premise: three film students disappear while shooting a documentary about the legend of a local witch; a year later, here is their footage. The advance word called it raw; buyers called it annoying. Several key distributors walked out in the middle, unnerved by all that jitter. "We'd all been so excited going in," recalls one executive. "None of us, none of the studio people shopping for movies, liked it." When a company called Artisan Entertainment signed the film for $1 million, a joke went around Sundance. The only scary thing about "Blair Witch," one rival said, laughing, was how much the distributor paid for it.

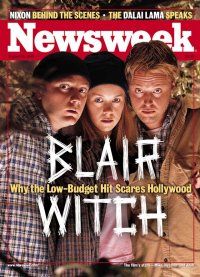

"The Blair Witch Project" is now getting the last laugh. Shot for a reported initial cost of $30,000, it earned $48 million in its first week of wide release--probably the most successful film ever, at least based on its production cost to revenue ratio. Studios delayed big-budget movies to stay out of its path. In a summer of brassy, oversold product like "The Phantom Menace" and "Wild Wild West," here was a stealth blockbuster, a low-key answer to what ails Hollywood. It had no stars, special effects or on-screen violence--not even decent lighting. In a typically rushed moment last week, Daniel Myrick, 35, who directed the movie with Eduardo Sanchez, 30, offered a simple explanation for its success. "It's like the Seattle music scene," he said. "Every now and then, art, whatever form it takes, gets back down to its roots. When you don't have money and resources, you're forced to get down to the essence of storytelling. Or at least have a good story." For a likably scruffy group of young actors and filmmakers, the success seemed a spontaneous victory of art over hype.

But is it? the saga of "the Blair Witch Tapes," as it was once titled, is more complicated than its legend-in-the-making. The story begins in 1992, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, where Myrick and classmate Eduardo Sanchez first pitched the idea to their film-school professor, Mary Johnson. "And I thought it was the lamest thing I'd ever heard," Johnson says. If nothing else, her reaction served as fitting preparation for the ordeal to come.

The original plan was to make a faux documentary in the style of the old "In Search Of" television series. Together with friend Gregg Hale, the directors concocted an intricate Blair Witch mythology, beginning in 1785, when a local woman, accused of witchcraft, was allegedly left to die in the woods. The story continued through a series of macabre murders and disappearances. The filmmakers invented historians, cops and townspeople to interview. To give the "mockumentary" some texture, they wanted to create a half hour of footage from the Blair woods. In June 1996, supporting themselves by making videos for Planet Hollywood, they placed an ad in Back Stage and began yearlong auditions for three actors to improvise and film all the action themselves.

Heather Donahue, 24, recalls her audition. "I sat down and Dan Myrick said, 'You've served seven years of a nine-year sentence, why do you think we should let you out on parole?' [There was] no 'Hi, I'm Dan.' [So] I just said, 'I don't think you should. I'm twice as angry as when I was put in here'." Donahue was living in Philadelphia, working in low-budget indie films; she was happy to note that this one actually paid. In October 1997, she joined Joshua Leonard, 24, and Michael Williams, 26, in the woods near Burkittsville, Md. They were told to expect the worst. "We told them upfront, 'You're going to be subject to intense psychological treatment'," says Myrick.

For six days and nights, the actors camped in the woods, getting dirtier and hungrier as they filmed each other on 16mm-film camera and Hi-8 camcorder. "Every time we crossed a log, we were carrying the whole production on our backs," says Donahue. In lieu of a script, each morning they received private messages in film canisters, and were told not to share them with the others. "Everything was on a need-to-know basis," says Leonard, who before the film was photographing rock bands for smallish magazines. "My notes were like, 'You don't trust Heather, take control'." At night, the directors would make noises and rustle the actors' tent to scare them. Production designer Ben Rock devised a creepy stick figure, obliquely menacing, and hung it in trees. Everything else they left to the cast's--and ultimately, the audience's--imagination. Though the actors would pass an occasional jogger, and sometimes cross a road, they began to feel cut off from the safety of the civilized world. "When you really felt secluded was when the [film crew] came in and adjusted a camera, then they'd leave, and you couldn't go with them," says Williams, who trained in theater. Edges started to fray. "Josh and Heather were at each other's throats from day one," says Myrick. "They really hated each other."

Myrick and Sanchez then began editing the 20 hours of footage into something more manageable. As they blended in some faked interview scenes, they found the canned stuff felt too cheesy. "We weren't digging it," says Sanchez. Besides, the woods footage was beginning to cohere into a story. They trimmed it to two-and-a-half hours and screened it for an audience in central Florida. There were some problems. "People coming out said they would have killed Heather themselves," says Sanchez. The two chopped Heather's shrill scenes, then chopped some more.

In need of money and distribution, they launched a rudimentary but clever Web site in June 1998. Though most movies had sites by then, offering cast photos and the like, Myrick, Sanchez and Hale stuffed theirs with lore about the Blair Witch, including fake newspaper clippings and Heather's "diary." Throughout, they never let on that the story might be bogus. On limited resources, they twisted the usual Hollywood marketing scheme: instead of broadcasting to the passive masses, they targeted the small, rabid and influential clique that might seek out a witchy Internet site. The compatibly cultish Independent Film Channel's "Split Screen" program aired a short documentary spot about the fake documentary feature. A small core audience was forming, and it was beyond presold; it was happy to be the sales force. "I thought [the story] was real and that's what first drew me in," says Jeff Johnsen, 33, who launched the first fan site last December. "When I found it was fictional, I just thought they were geniuses. And I wanted everyone else in the world to get sucked into this." Fans set up hypertext links between the various sites, as well as to other film or occult sites, funneling thousands of people a day through the Blair Witch experience.

After Sundance, Artisan Entertainment dramatically upped the ante, eventually committing up to $15 million for marketing and distribution. And it kept its focus close to the silicon roots. "We wanted the [Web] site to be like a weekly program, with new information each week," says John Hegeman, 36, the company's marketing head. They added outtakes from the "discovered" film reels; they posted fake historical texts. Another week, a taped interview with Heather's "mom" suggested a police cover-up. Hegeman marshaled a rigorous marketing plan, including tie-ins for books and TV specials, and blitzkrieg campaigns on college campuses--all done below the radar, so it wouldn't register as hype. As computer jocks added their own thoughts and conspiracy theories about the bad mojo in the Burkittsville woods, the movie--still months from release--became an ancillary product in a richer Blair phenomenon. Eventually Artisan would fill this realm with commercial merchandise, including a soundtrack CD--an oddity in a film with no music. The line between marketing and entertainment vanished as completely as Josh, Heather and Mike.

There was just one problem. At a New Jersey screening this spring, the audience again panned the movie--"some of the most dismal scores in recent history," says an insider close to the project. The directors cut five minutes and replaced some video footage with 16mm film, which was less shaky; Artisan pumped $341,000 into a better sound mix. Hegeman's 11-person marketing team redoubled its efforts.

Trailers for the film followed a savvy strategy. Instead of shilling for "Blair Witch," they offered only a blurry shot, a scream, a creepy stick figure--hype posing as insouciant anti-hype. The company leaked the first trailer to the gadfly Web site Ain't-It-Cool-News and the second to MTV news--hype posing as scoop. Marketing "street teams," like those pioneered by hip-hop music labels, papered 40 or so college campuses with cryptic "Missing Person" fliers just before school let out. "So in summer, when everyone's dispersed throughout the whole country, we had created a buzz throughout the whole college marketplace," says Hegeman. Artisan brokered a key deal with the Sci Fi Channel, which had been interested since Sundance: they jointly financed "Curse of the Blair Witch," a deft one-hour mock documentary about the Blair Witch legend, created by Sanchez and Myrick from the footage they'd shot for their original conception of the film. It premiered July 12, the Monday before opening day, becoming the channel's highest-rated special ever; for six subsequent airings, viewer numbers held steady. By the time the movie opened, the audience was primed.

The real key, though, remains the film. Unlike recent horror hits like "Scream," it avoids irony and self-reference, which distance viewers; instead, its porous surfaces draw them in. "You never see anything horrible," says New York fan Amina Runyan-Shefa, 24. "You just see kids your own age who are scared to death. It really works." Though the jumpy style has alienated some older viewers, it taps a generational linguistic trope, one more fundamental than the latest slang. To a Gen-X and -Y audience raised on handheld TV programs like "Cops" and MTV's "The Real World," deliberately low-fi recordings by groups like Pavement or the Wu-Tang Clan, and the funky misspellings of Internet newsgroups, grainy equals real, immediate. Wholly created by the production process, the jerk of a video camera or the crackle of a scratchy vinyl record has come to stand in for the truer reality behind the process. The rest, as they say, is just showbiz.

For the young cast and crew, the film's success is more than just a vindication. All along, says Michael Williams, "I thought, 'Is some studio going to buy this and reshoot it with Brad Pitt?' Because that was an option." Now all three actors are getting more auditions. Sanchez and Myrick are weighing thoughts on a "Blair" sequel or "prequel," possibly three or four, each done in a different style. And for the movie executives who laughed during Sundance, the movie's biggest scare is just arriving. The Blair Witch saga may be fictional, but it will haunt Hollywood for some time to come.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.