Any time I'm offering my two cents on a subject, which is often, I typically end with "but that's just one black man's opinion." It's an expression I've had in my lexicon for years. I stole it from my father, who says it with such charming humility that it cracks me up every time I hear it. When I say it front of white people though, the reaction is usually an uncomfortable one. I'm open to the possibility that I lack my father's charm, but I believe the discomfort mostly comes from white people feeling that it's inappropriate for me to suggest that being a black man and being a white man are somehow different. It is a truth better left out of polite conversation.

Take just about any measure of social or economic success you want to single out, and chances are, black men are foundering in it at rates so alarming, you have to assume the alarm has a snooze button. The unemployment rate for black men—17.8 percent, according to the most recent job report—is double that of our white counterparts. A report issued last month found that the on-time high-school graduation rate for black males was a dismal 47 percent. It's no wonder that in another study, which found that levels of self-reported happiness has increased for blacks while remaining static for whites, the uptick is primarily due to black women. Black men, it seems, are still pretty miserable. Clearly, being a black man and being a white man are different roads.

This is what makes the conversation about the redefinition of manhood a tricky one, because it really only applies to white men. Black men, due to such dire disparities, have never been able to define their manhood through their utility or social primacy. The identity crisis white men are now muddling through has been basic existence for black men for as long as we've been in this country. While white men are figuring out how to carve out a new definition of manhood, black men have been trying to figure out how to catch up with the old one.

In some ways, trying to mimic a traditional model of masculinity has been part of the problem for us. If men define themselves through doing blue-collar work, and getting dirty and making things with their hands, they find themselves in a pinch when those sectors shrink, as construction and manufacturing have recently. That's an issue that affects white and black men in the same way. The difference seems to be in pursuit of education. When white, blue-collar men find themselves out of work, they're more likely to have at least a high- school diploma to fall back on.

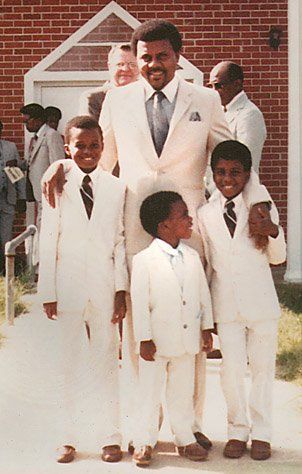

I'm fortunate that this narrow definition was never modeled for me. My father often told war stories of his days working in a steel mill, but they were mostly to illustrate how much hell he was willing to endure to pay his college tuition. He eventually became an attorney, and married my mother, an elementary educator, whom he met while attending Howard University. He's street smart and athletic, but a brain and a creative above all. There was an occasion when I was much younger, when my dad and I went to the mall, and an unoccupied, improperly parked car starting rolling through the parking lot. He jumped behind it and pushed, guiding it slowly back to a safe resting place. I thought he was Superman, and to this day I'm still not entirely convinced that he isn't. I don't consider him any less of a man's man because he writes poetry and drives a Prius.

I'm clearly biased, but I think my father is a good model for the brains-meets-brawn type of masculinity that men should be striving toward. Men of all races need to accept that their physicality or musculature is not what defines their worth, and that they need to develop different facets of themselves equally so they don't get left behind. I think it's all right for men to still judge their own value by their work—Rome wasn't built in a day—but at the very least, what defines that work needs to evolve.

But it's not yet time for black men to stop striving to eliminate the disparities that fuel so many sobering newspaper stories. The mild schadenfreude present in the stories heralding the end of men suggests that some people are missing the point that not all men ever reached the apex we're now allegedly plummeting from. The goal for black men should still be the educational and professional success and utility that some white men have seemed to take for granted. But using the same ways of getting there—by doggedly pursuing stereotypically "manly" careers and embodying goofy, outmoded, macho identities isn't the way to get there. That, I can say with confidence, is not just one black man's opinion.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.