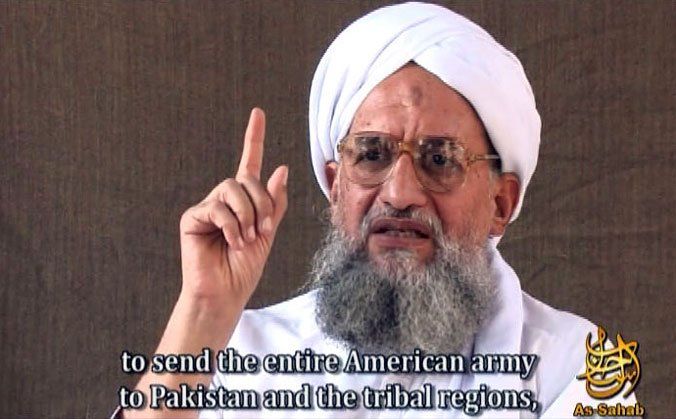

A year after the death of Osama bin Laden, American special operators are training their sights on his successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, the former Egyptian Army surgeon widely regarded as the mastermind of major attacks against Americans and other targets. And forces loyal to Zawahiri, who affectionately call him "Glasses" because of his trademark oversize spectacles, are determined to guard their leader.

Zawahiri's safety was the main subject of conversation when several senior al Qaeda operatives and a handful of other militants sat down for a dinner meeting in North Waziristan six months ago, according to a well-placed Taliban source. The host of the dinner, from a prominent Taliban family, had a sheep slaughtered in honor of his Arab guests. Over a meal of mutton kebabs and pilau, the men expressed concerns about Zawahiri's security in light of bin Laden's bloody end. They said Zawahiri's handlers and tribal hosts had strongly advised him "to move to a new place," to stop using electronic devices, to limit his exposure by issuing fewer audio and video propaganda tapes, and to exercise extreme caution in dealing with couriers.

"We are hoping he can avoid being captured by the U.S. for at least 10 more years," the source says. One of the al Qaeda operatives at the dinner, which took place outside the town of Miran Shah, asked if the Afghan Taliban would consider harboring Zawahiri if he decided to hide in Afghanistan. According to the Taliban source, the Afghan was noncommittal.

Taliban and al Qaeda operatives who have met Zawahiri say he is highly respected in militant circles, both as a thinker and a doer. He's not nearly as charismatic as bin Laden, but in some ways, he's more important. Bin Laden was the face of terror, but Zawahiri is the mind: an important ideologue as well as an operational commander.

He's under increasing pressure now to carry out a fresh act of headline-grabbing mayhem. "Zawahiri needs to terrorize in order to really cement his position as bin Laden's long-term successor," says Bruce Riedel, a former CIA official who has advised the Obama administration on counterterror policy. Yet the new al Qaeda chief faces a dilemma: the more involved he gets in planning and propaganda, the more exposed he becomes. And he can't conduct terror operations if he's dead, much less serve as a symbol of al Qaeda resilience.

American intelligence on him is sketchy; the last time U.S. agents are known to have had actionable intelligence on his whereabouts was in January 2006, when they learned that he had been invited to an Islamic holiday dinner in a mud-walled compound on Pakistan's border with Afghanistan. A Predator drone fired a salvo of Hellfire missiles at the compound, killing some 18 people, including several al Qaeda militants. But Zawahiri was not among them.

"There are indicators that some elements of the Pakistani government may be protecting Zawahiri," says a U.S. intel official who did not want to be named discussing sensitive information. "We have reports that he's been hanging out in Karachi for brief periods, and we just don't think he's going to be doing that without a lot of people knowing about it."

At the moment, it would be politically fraught, however, for American special operators and CIA agents to carry out an attack even in the remote tribal areas, much less in a city. Pakistan's political and military leaders, humiliated and furious that Washington kept them in the dark about the bin Laden raid and other missions, have forbidden the United States from conducting drone strikes in their territory. American forces are respecting Pakistani wishes—for now—in an effort to "lower the temperature," says one senior administration official. But that forbearance won't last long. Eventually, American officials tell Newsweek, offensive drone operations will restart, with or without Pakistan's approval.

The militants who gathered for dinner near Miran Shah were still mourning bin Laden's death at the time. They recalled the care he had taken to protect himself. Bin Laden's trusted aide and courier, Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, had devised ingenious ways to move his leader from one safe house to another in Pakistan. He had hidden bin Laden inside a large box that was fitted at the bottom of Pakistan's brightly colored transport trucks. The box would be stuffed under cargoes of cement, wheat flour and rice sacks, or even under a noisy collection of goats, sheep, or chickens.

The men blamed the courier, a Pakistani Pashtun from the tribal areas who had lived in Kuwait for a time, for bin Laden's death. "A Qaeda investigation showed that al-Kuwaiti's carelessness provided the clues for our enemies to discover the sheik's house," says the Taliban operative. "He was not a traitor, but his mistakes led to the great sheik's death." The blunders included driving the same car every time he went to the compound inside the Pakistani garrison town of Abbottabad and using a cellphone that could be monitored.

The militants at the dinner didn't want Zawahiri to make similar mistakes. They lamented the heavy casualties that armed drones had inflicted on al Qaeda's hierarchy. All of them had heard that bin Laden had become increasingly depressed and detached as the death toll of his lieutenants mounted. "The sheik's last days were painful, as he was hearing bad news all the time about the loss of the remaining Qaeda leaders," the source says. "The sheik's last year was not a good one."

Zawahiri is more connected to day-to-day operations. He was involved, for instance, in the 2005 bombing of the London Underground and in the assassination of former Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto in 2007. It seems he also played a role in deploying a Jordanian double agent to bomb a CIA base in Khost, Afghanistan, in 2009. The CIA operatives who were killed believed they were about to receive key intelligence on Zawahiri's whereabouts. "That attack gave a big boost to Zawahiri's credentials as a terror planner," says Riedel.

Zawahiri can take heart from the fact that as pressure has grown on al Qaeda's central command, affiliated groups have sprung up around the globe: in Yemen, Somalia, and North Africa, among other places. But like bin Laden before him, Zawahiri is now an important symbol—of either the success or failure of the global jihad.

It'll be much easier to mount an effective operation against Zawahiri and his close circle of aides if the United States has the support—explicit or otherwise—of Pakistan. Though several top al Qaeda figures have been killed or captured in Pakistani cities, Zawahiri may still be living in the tribal areas along the Afghanistan border. Drones can learn a lot from the sky, but the region is large, and human intelligence is vital. The Pakistanis could help get that, but cooperation requires trust—on both sides.

There is none. "This time it's the lowest it has ever gone," says retired Maj. Gen. Mahmud Ali Durrani, a former ambassador to Washington. He blames both sides. "We have failed at convincing America that we are with you, that we want to get rid of these militants," says Durrani. Yet Pakistan believes the United States does not respect the country's sovereignty and treats it like a vassal state.

The distrust only got worse after the bin Laden raid. President Obama, fearing a leak, ordered that Pakistan be kept in the dark. The United States, in fact, expected that the Navy SEALs would bring back evidence that Pakistani intelligence was cooperating with al Qaeda. Newsweek has learned that shortly after the SEALs stormed bin Laden's hideout, federal prosecutors were laying the groundwork to issue sealed indictments against members of the Pakistani government or anyone else they believed had aided bin Laden. The charge, according to two law-enforcement sources, would have been "harboring a fugitive terrorist."

The SEALs carted away boxes of computers, hard drives, thumb drives, DVDs, and thousands of documents. It was the greatest intel haul on al Qaeda's operations and habits since 9/11: 3.4 terabytes of information, according to an intelligence source, including a personal journal by bin Laden, outlines for aspirational plots, cellphone numbers, and other contact information for al Qaeda allies. No smoking gun on Pakistani complicity was found, however, and no indictments were returned.

It's not just the bin Laden raid that exacerbated ties. In January 2011 CIA contractor Raymond Davis shot and killed two alleged Pakistani robbers on a Lahore street. Then in November, U.S. warplanes killed 24 Pakistani soldiers in an airstrike along the Afghan border. A U.S. investigation concluded that mistakes by both sides contributed to the deaths. The Pakistani military angrily rejected that conclusion, saying the attack was unprovoked and deliberate.

Pakistan retaliated by closing down the vital supply line for NATO cargo moving to Afghanistan. It also expelled American personnel and drone aircraft from a Pakistani airbase. Most Pakistanis see the drone operations as a violation of sovereignty, and they decry the civilian casualties that sometimes result. Not just ordinary Pakistanis but also intelligence and counterterror agents often view the United States as an enemy. "Even right now we are collecting data on each American and each Pakistani working with the U.S. embassy and everyone they are in touch with," says a Pakistani counterterror officer who declined to be quoted by name.

Last week talks began between the United States and Pakistan to try to "reset" the relationship. The drone issue is the toughest challenge. Even the U.S. government is divided over what the American position should be. Some would like to appease Pakistan by restricting the circle of possible targets for the drones and to give the Pakistanis a greater sense of involvement and control over what happens in their territory. Others say no way: too often in the past, Pakistan's ISI spy service had tipped off targets before any missiles were fired. During one period in 2007, there were seven consecutive drone attacks in which the targets managed to slip away, according to a former Obama administration official who was briefed on the matter by the CIA.

U.S. officials have repeatedly confronted their Pakistani counterparts with evidence of ISI double-dealing, but that has made little difference. On one occasion the U.S. provided surveillance imagery of Pakistani soldiers waving arms shipments for the Haqqani faction of the Taliban across the border into Afghanistan. In the weeks after the raid on bin Laden, the U.S. military twice provided Pakistan with intelligence on bomb-making factories in its territory. Both times, the militants escaped before the weapons facilities could be attacked. "The reality is that Pakistan remains a permissive environment for terrorism—even though al Qaeda has killed thousands of Pakistanis," says a U.S. official.

If the U.S. gets Zawahiri in its sights, it won't want to risk compromising an operation to take him out. The al Qaeda leader's safest bet might be to hide as deep inside Pakistani territory as he can get. Riedel believes he's probably already there. "I think the CIA would be looking for something that looks an awful lot like Abbottabad," he says. "A safe house in an urban area near a military base. That's been the signature of almost all of the senior Qaeda operatives who have been killed or captured."

The problem for Zawahiri, however, is that "the CIA has demonstrated that it can break the code," says Riedel. "Bin Laden actually practiced pretty good operational security, but Zawahiri has to take it up a notch. If I were him, I would be worried. I think we'll find him, and I don't think it will take 10 years." Once again, Pakistan may learn about it only after the fact.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.