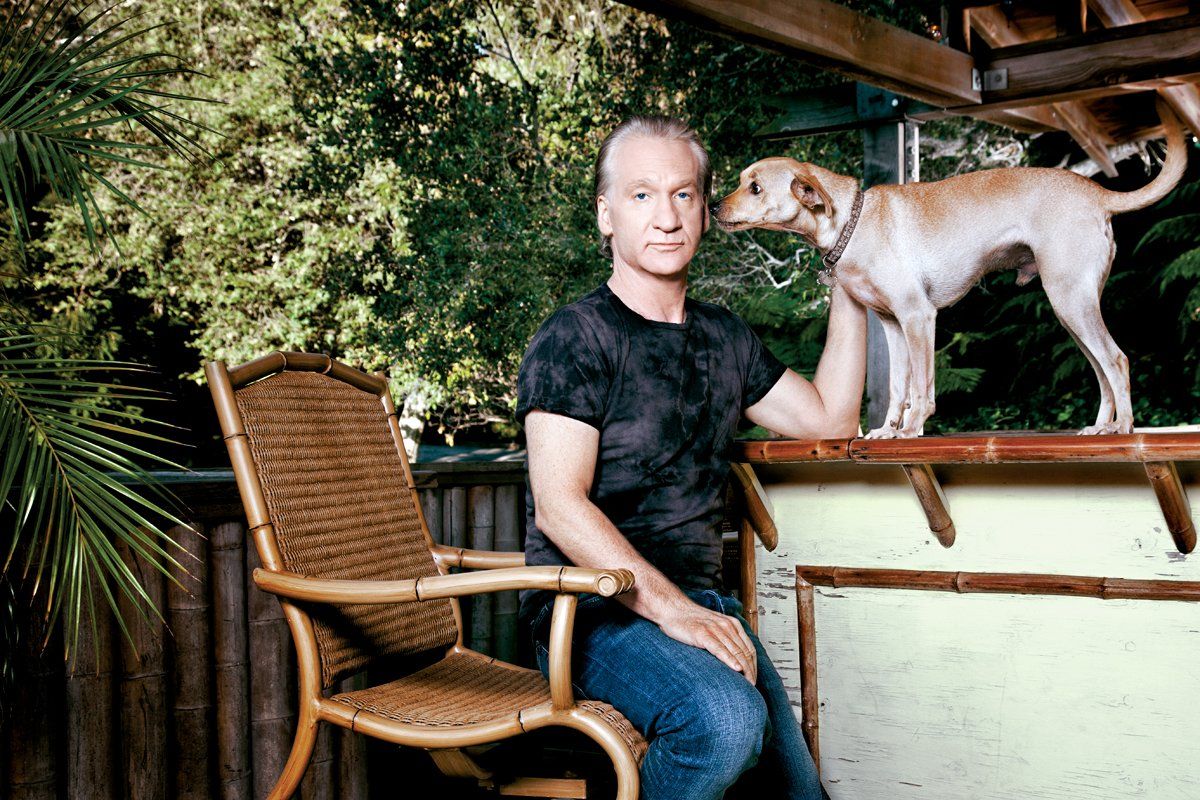

In many ways, Bill Maher is a testament to the enduring power of the American Dream. As a shy, precocious 10-year-old growing up in white-bread River Vale, N.J.—the son of a radio newsman and a nurse—he habitually stayed up late to watch The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. He vowed silently to himself ("I would never have had the balls to say it," he recalls) that one day he not only would be one of Johnny's guests, he'd have a television show of his own. "I didn't want to be on it, I wanted to own it," Maher tells Newsweek, noting that he ended up making 30 appearances on the late-night legend's show. "I wanted to be Johnny Carson."

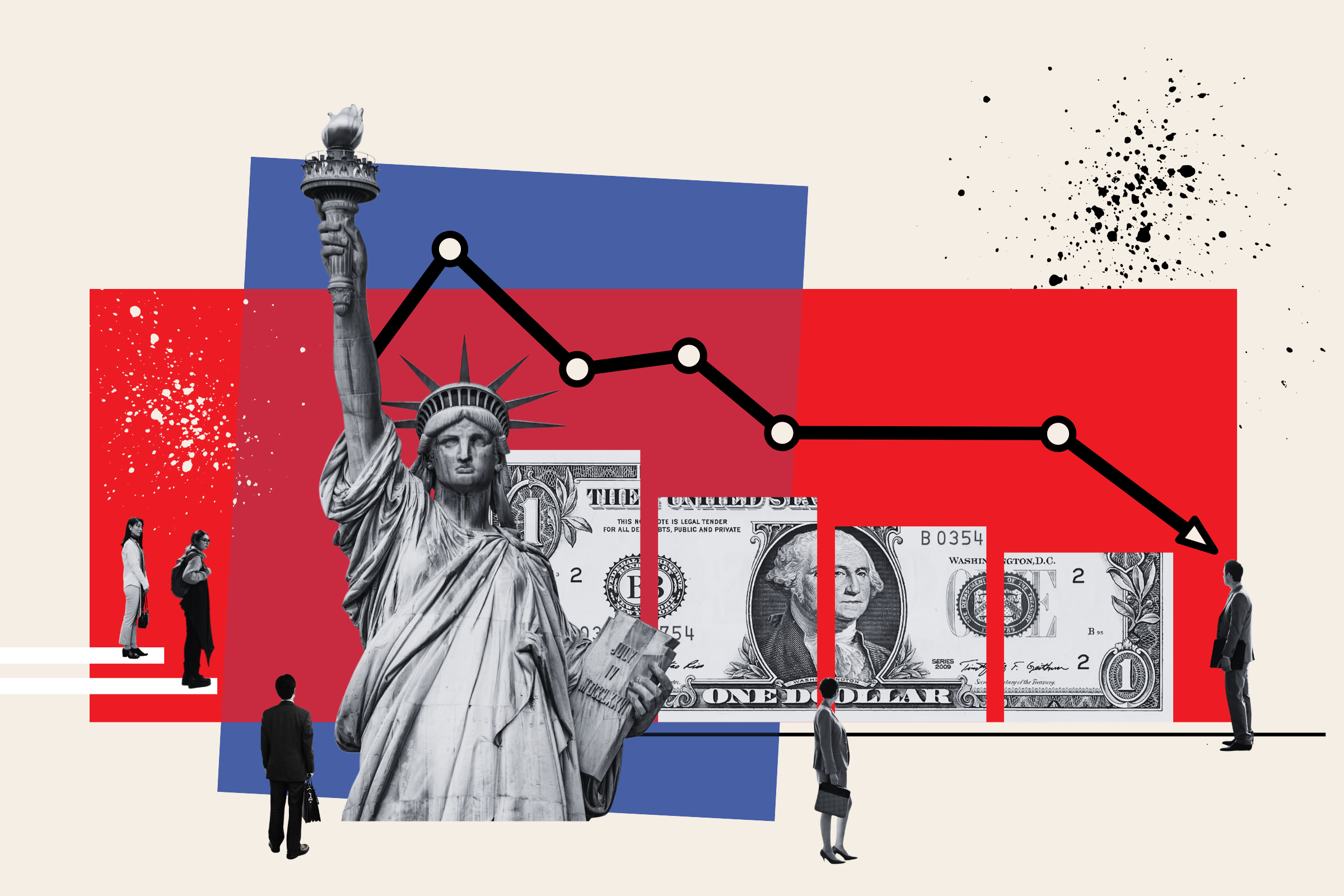

As he reminisces about his race to the top—a life of wealth and fame, flashy women, and critical acclaim, only briefly punctuated in those struggling early years by a stint as a dope dealer in Spanish Harlem—Maher, 55, steers his all-electric Tesla Roadster (price tag: $120,000) toward downtown Los Angeles. His destination: the bedraggled encampment of tents, Porta Potties, and angry souls ringing City Hall known as Occupy L.A. It's the local chapter of Occupy Wall Street, which has quickly become a national protest movement against social injustice, income inequality, and a hodgepodge of grievances amounting to a raging rebuke of the American Dream.

"They Poison Our Air, Water, Land, Bodies, Minds, and Dreams," says a handpainted cardboard sign resting in the mud on the periphery of the tent city and crudely capturing the spirit of the gathering. There's little doubt who "they" are: the Upper 1 Percenters—a malevolent elite of grasping corporations, greed-head bankers, and corrupt politicians who have managed to ruin the economy for the other 99 percent, betray the public trust, and bring millions of hard-working citizens to their knees.

Carefully stowing his Tesla in a parking structure—until today, Maher confides, he'd never risked driving it on a freeway for fear of hitting a pothole and blowing a tire—he enters Occupy L.A. on the down low, dressed in celebrity incognito, a black leather jacket covering his wiry 5-foot-8 frame and a New York Giants cap shoved down over his face. He is, of course, recognized immediately.

In due course, Maher is surrounded by a crowd of ragtag admirers, many of them looking the worse for wear, having braved the elements for five or six weeks. Over the throbbing of nearby bongo drums, Maher suddenly finds himself conducting an impromptu teach-in on the state of the American body politic.

"The most important thing is what you're doing—so keep doing it," Maher tells the crowd. "It sends a real message that people are in the streets because it's the only other way to get your voice heard if you don't play the game the way it's been played, with lobbyists and congressmen who are too influenced by corporate money."

To whoops and applause, he adds: "Don't let them convince you to come inside and put on a suit and hire a lobbyist. That's how you lose. This is how you win."

At which point a young man with stringy blond hair strolls by and coos campily: "He's sooo handsome!"—prompting Maher to start laughing.

"Hemp will save the world!" shouts a jeans-clad woman with graying hair.

"If I had some hemp, I might agree with that," retorts Maher, a publicly enthusiastic marijuana smoker.

"You should run for office," an aging Latino man urges. "We need senators like you." More whoops and applause. "You gonna run for president?"

"No, no, I can't," Maher replies. "First of all, I'd lose. We can't even get an atheist in Congress, let alone for president." Later, he elaborates: "I think religion is bad and drugs are good. How can you get elected, just starting with that?"

He would certainly get the support of some voters, however. For the past two decades, and especially since 2002 as host of the HBO hit Real Time With Bill Maher, he has been channeling their dyspepsia and discontent—and his own—into a sharply amusing version of righteous indignation. His Friday-night rants have assailed such evils as the general stupidity of the citizenry, the hypocrisy of our leaders, the incompetence of public education, the timidity of Barack Obama, and, of course, his favorite target: the toxic effects of religion. Bad times, it seems, have been good times for Maher.

His latest book, The New New Rules: A Funny Look at How Everybody but Me Has Their Head Up Their Ass, carries on Maher's sacred mission to, as he writes in the foreword, "put a voice to life's gripes, everything from the petty annoyance of that little sticker on your supermarket plum to the brazen injustice of a Supreme Court that sides almost solely with corporations over individuals." (He's dedicated the book to his girlfriend, Jasmine Boussem, a French-born entrepreneur he's dated off and on for the past five years and who's taking graduate courses in social psychology at Harvard. It's a serious relationship, but Maher—a sometime visitor to the Playboy Mansion—is still on the fence about giving up his bachelorhood.)

Maher might be going for laughs, but he is genuinely, and perpetually, outraged.

"What Bill does is funny, but also dead-on serious," says HBO's president of programming, Michael Lombardo, who describes Maher as "infuriated by the world around him." He adds: "I think his viewers are people who have been outraged by the absurdity of modern politics, and his audience has recognized the brokenness of what's been going on."

Chris Rock calls Maher simply "the best political satirist in the world." Rock credits Maher with reviving his moribund post–Saturday Night Live career by hiring him as a 1996 campaign correspondent for Politically Incorrect, the Comedy Central panel show that migrated to ABC until Maher made some politically incorrect comments about 9/11 (suggesting that the terrorists were brave and the U.S. military was "cowardly") and the network summarily canceled it. "I think he is the best when he is really angry," Rock tells Newsweek, "and he's actually angry. He actually cares what he's talking about. This was not a career decision to become 'this guy.'?"

Frequent Real Time guest Seth MacFarlane, the man behind Family Guy and American Dad!, says Maher is "great at peeling away the bullshit and exposing nonsense as nonsense. More than anything else, he is undeniably sensible. He never comes off as preachy—it's always about the comedy first. But he also has a conscience."

Another Real Time favorite, Salman Rushdie, ranks Maher with Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert as "the most astute political commentators in America." He adds: "This mounting sense of injustice in America, of which Occupy Wall Street is one manifestation, is something that Bill has managed to articulate brilliantly."

Maher modestly downplays the importance of his comedy, calling it "a distraction." He explains: "I love it to death, but it really is building a ship in a bottle for me. I really don't think I have any superiority to someone who builds a ship in a bottle. My ship in a bottle happens to be my standup act."

He says it's pure accident that he became wealthy by learning to tell jokes and is offended by the Republican truism—most passionately articulated by Herman Cain—that if you're poor, you have only yourself to blame. "It's so ridiculous, it's so arrogant, and it's so foolhardy because what makes someone rich is a fluke," he says. "Is the CEO who makes a thousand times more than the average worker really a thousand times smarter? Does he work a thousand times harder? No. Even if you're the CEO of Godfather's Pizza, that's a certain skill. But does it philosophically make you more worthy of riches than my sister [Kathy Maher], who's a teacher? Or the troops who we're constantly lauding as the greatest people in the world but who we pay practically lower than anybody else?"

Maher credits his sense of social justice to his late parents—his Irish-Catholic father, Bill Sr., who fought under Patton in World War II, and his Jewish mother, Julie, who served in Germany as a wartime nurse and, unlike her enlisted-man husband, was an Army first lieutenant. Both were funny people, both were impassioned supporters of the civil-rights movement, and his father especially bequeathed him a sometimes querulous temper.

Maher says he's a nicer person than he used to be. And Kathy Griffin—who, in her 2009 memoir, Official Book Club Selection, referred to him as "a prick"—agrees that he has evolved. "I wouldn't call him the most approachable person," she says, "but once you get to know him, he definitely warms up. And also, he's a tough customer, which I like."

Maher has mellowed with age and success. "Look, can I viscerally be as angry as people who literally don't have a pot to piss in? I don't think I can," he says. "But that's something I got from my father—an empathy for the common man. I certainly know what it's like to be poor. I was dirt-poor throughout my late teens and 20s. I lived in the slums of Spanish Harlem, in places that didn't even have a toilet in the apartment. And that's good for you, but not for your whole life."

In his comic sensibility, Maher is the natural successor to the hilariously transgressive George Carlin as well as Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, the truth-to-power speakers of the 1950s and 1960s. But he lives like a Reagan Republican in a shining city on a hill—actually a large estate in a rarefied aerie of Beverly Hills. He purchased part of it from his next-door neighbor, Ben Affleck, after the movie star's fiancée at the time, Jennifer Lopez, urged him to unload his bachelor pad so they could live together in more appropriate digs. "He sold that beautiful piece of land and I was lucky enough to buy it," Maher says, adding that the main house burned down when Drew Barrymore owned it, but it came with a small guest house and a basketball court. "It never went on the market, and it wasn't really all that expensive."

The irony of his situation is not lost on Maher, the professional ironist, as he mingles with the huddled masses at Occupy L.A. And when a disheveled protester asks him if he'd buy some socks for the tent dwellers, Maher immediately says yes.

"How about dry socks?" prompts the Latino man who wants him to run for office.

"Of course," Maher answers. "What—I'm gonna send you wet, moldy socks? What kind of schmuck do you think I am?"

The next day, Maher sends more than 100 pairs.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.