If President Joe Biden wants to heal the divisions in U.S. politics, he needs to stop all this talk about "unity" and instead focus the attention of all Americans on a common foe: toxic polarization.

That's the advice the Biden administration has gotten from psychologist Peter Coleman. In a series of memos, Coleman, a mediator with experience in conflicts as far-flung as the Middle East, Haiti and Africa, has advised the new administration that the best way to repair and reverse the extremism in U.S. politics is to focus Americans on the virulence of the nation's divisions and mobilize them to attack the problem.

Coleman has come to this conclusion after traveling the world consulting with peacemakers and policymakers and studying the societal conditions that often precede war, as well as those that often lead to peace. The current tensions in the U.S., Coleman argues, have their roots in the cultural and political shocks of the 1960s, which upset the existing order, and set the stage for a new era of political partisanship that began in the early 1980s and has been growing ever since.

Today, the nation is once again experiencing disruptive cultural and political shocks. "Our Capitol building was overrun and five people were killed," Coleman says. "That is a historic event in America. The evidence suggests more is to come. Unless we do something to change course, extreme forces are going to make things worse."

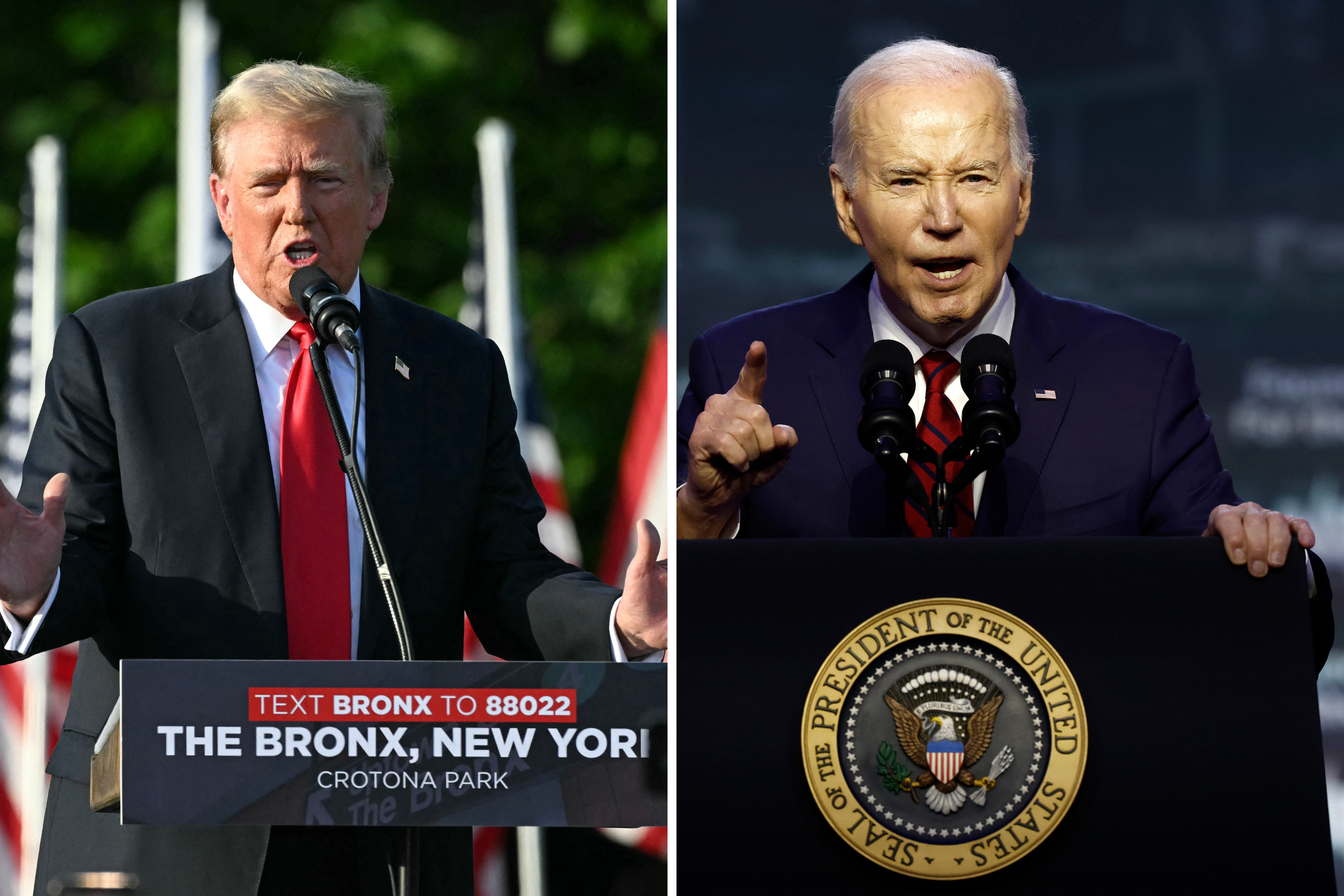

Although the current state of affairs is dangerous, Coleman believes that the nation may be ripe for a new approach—86 percent of Americans are fed up with the "dysfunctional divisiveness" in our nation and are eager to overcome them, according to one poll. We may have reached a tipping point, he says. "Trump, COVID, racial injustice and storming the Capitol is a pretty powerful wake up call for America. I'm optimistic that enough people will say 'enough,' and that will start to move us in a different direction. But we have got to take advantage of this opportunity to do the work that's necessary to shepherd that process."

Although Washington can support this effort, ultimately it has to come from communities. Coleman, director of the Morton Deutsch International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution at Columbia University and author of the forthcoming book The Way Out, How to Overcome Toxic Polarization, spoke with Newsweek about how the nation can heal.

Newsweek: What do you mean by "toxic polarization"?

Peter Coleman: Political polarization can be a healthy phenomenon and a necessary phenomenon, particularly in a two-party system like ours, because you need to have tension and different points of view that come together to move us forward. Toxic polarization is when you get into these almost psychotic camps that can't even imagine the other side's perspective. In the 50s and 60s, there was actually a call for more polarization in politics because we were sort of too homogenous, the parties overlapping so much. But then in the 70s, we started to see this movement away, with a big turning point coming in 1980s.

How do you measure it?

In Washington, you can ask, does Congress cross the aisle and support people on the other side, or do they just really sort of start to stonewall? That's one measure that they've been able to track since 1869, and that shows a clear upward trajectory, beginning about 1980. There's also evidence about attitudes on the ground, about citizens and their take on the other side. Trump was not the cause, he was in some ways the effect. He certainly exacerbated it. He'll go away in some capacity, at least as President, but the underlying dynamics will remain.

What are those dynamics?

If you have a race-baiting president, that definitely triggers a lot of trauma and a sense of injustice. [Senator] Ben Sasse says we're in an epidemic of loneliness and disenfranchisement because we don't believe in the church and communities and our families are fractured, so we look for tribal belonging in our political parties. It's a valid point. [The scholar] Jonathan Haidt [focuses on] differences in moral values—his research has found that there are a set of moral values, and liberals and conservatives differ on what they prioritize [conservatives favor loyalty and purity; liberals favor caring for communities and justice]. Others say the internet ecosystem and the entertainmentization of journalism and media have split us. We're addicted to the media, we're addicted to enmity.

I think they are all right. It's really how these things sort of align and start to create dynamics that become very change-resistant, because there are so many things that are feeding it. It's akin to a vicious cycle—a complicated set of problems that feed each other in unpredictable ways and are change-resistant. Just bringing people together to talk can only have a limited impact because so many other elements are ripping us apart.

What lessons can we draw from other places that have experienced toxic polarization?

Scholars who have looked at 200 years of data—on how states interact, trade and [fight] wars [etc]—find that something like 95 percent of the longer-term destructive relationships that states get into are preceded approximately 10 years by some major political or cultural shock that's dramatically destabilizing—an assassination attempt, or a coup attempt, or the end of the Cold War.

You've said that the current polarization in the U.S. started around 1980. What caused it?

I would suggest that you look to major cultural shocks in the late 60s and early 70s. You had a lot of tumult in America—several political assassinations, a culture war, an anti-Vietnam movement. And about 10 years later we settle into these divisive patterns.

Somewhere between 75 percent and 90 percent of these long-term problems, when they end, when they deescalate, when they change—they've also followed some kind of major political shock. The combination of COVID-19 and Trump constitute a major political shock to our system. It's a political shock on steroids. Sometimes these things destabilize us enough that they provide fertile ground for really changing directions, and for bringing the country together. That doesn't mean it will happen, but it does mean the time may be right for something like that to happen.

When a complex system is highly destabilized, you see changes that lead to other changes that lead to other changes, and across some threshold you see a major change. That's what we've seen in political polarization in this country. Right now, we have a unique opportunity to affect real change because our government and our population has been increasingly moving towards war since the mid-1970s.

What can the Biden Administration do to bring us together?

Here's my frank assessment. I don't think a presidential administration is going to be able to manage this, because they're in the middle of the conflict. They can certainly not exacerbate it and get out of the way. They can offer constructive solutions to real problems like COVID and joblessness and racial injustice that can start to reduce the resonance and grievances of many of the communities and take the heat out of a lot of the current tensions. But this really needs to be part of a social movement.

What kind of "constructive solutions" might Biden offer?

The principal thing I would recommend that Biden do is not talk about unity and healing yet. One of the things we've learned from peacebuilding is you don't go into a war zone and tell people to reconcile. Instead, you talk about toxic polarization as a pathology in our communities, our homes, and the impact it has on us personally, our children's health and our community's health.

The framing is critical. [The Biden administration] should back off healing and unity and say, 'we need to address this pathology of toxic polarization like we're going after COVID, because it's a first order problem. If we can't come together in our reality and our problem solving, we can't tackle these other problems.'

Biden needs to genuinely listen to communities. But what it really is going to take is a social movement, and the infrastructure for that social movement is already there.

What do you mean by existing infrastructure?

At Columbia, we've been gathering the names of bridge-building organizations that are in different spheres. In America, most are community-based. They're not like the professional organizations that work overseas. They mostly spring out of community tensions, maybe a local issue that divided a community in a church or local government and then if they're effective they last. There are thousands of those groups across the country. In addition, there are groups in journalism, and in politics, and in media, and elsewhere that are actively working to try to bridge divides. You have these instances of "positive deviance." These are people effectively staying in communication and building bridges in places where most people can't because we can't stand each other or tolerate each other.

Gabriela Blum at Harvard studied Kashmir and the Israel-Palestine conflict and other long-term protracted conflict zones. She finds that there are groups and individuals that are somehow effectively managing, even under the most difficult circumstances, to stay in communication with the other side and to build bridges. They're sometimes surprising groups. Like fishermen in Mozambique, who would fish and be able to go across enemy lines, because people needed their food. They were bringing nourishment to the combatants, but they were also a source of connection and information that helped people begin to understand each other. These are what I call the community immune systems.

Are there any examples of effective efforts of this sort in the United States?

In 1994, a man named John Salvi drove to Boston and opened fire in two women's health clinics and ended up killing three women and injuring many others. He was a pro-life zealot. This was a time in Boston when rhetoric and vitriol around abortion was at a fever pitch. Boston in particular has a long history of pro-life and pro-choice activism that dates back decades. Then this event happened where Salvi came in and shot these women and it was a rupture. It was a destabilizing rupture. The mayor and the governor called for talks, and the archdiocese called for de-escalation. But a group called The Public Conversations Project, which had worked in abortion, asked three pro-life and three pro-choice leaders in the community to come together for a short period of time in dialogue. They agreed to meet four times. It was difficult, but it was worthwhile. They extended it and ultimately engaged in secret dialogues for almost six years.

In 2001, these six women came out together and they co-authored an article in the Boston Globe called Talking With the Enemy. They all agreed to basically drop the rhetoric and the vitriol and speak as honestly as possible about what these issues meant to them. Slowly over time, they developed such respect for one another that they really developed these close emotional bonds, but they also became more polarized on the issue. The more they spoke personally and honestly about what it meant to the other, and the more their relationships across the divide became important to them, the more difficult it was. But they learned to work together to avoid violence in the community. They learned to find common ground for young mothers and funding work for young mothers. The dynamic between them change profoundly, even though their attitudes on the issue became more polarized.

And that's the key. These kinds of divisions don't have to be toxic. It's a profound metaphor about the power of these community-based structures. Bridge-building groups have networks within communities and the capacity to ultimately affect broader levels of change.

The Biden administration can help us—at the community level, at the state level and at the regional level—to understand where the resources are. I've been recommending a convening of groups to map the ecology in communities, in states and then in regions of the country, where we start to realize who's there.

Are Americans ready for this kind of change?

Research on ending protracted conflict tells us that people need to be sufficiently miserable with the status quo. The accumulation of emotional exhaustion that is everywhere, including my hometown of Dubuque, Iowa, [means that] people are ripe for something else. But they need to understand what that something else is. They have an alternative where they could save face and move forward.

A report by More in Common, an international group that studies polarization, hasfound that people are tired of the dysfunction. They see a growing middle majority of what we would call "exhausted Americans." In 2016, after Trump's victory, two-thirds of Americans were exhausted, fed up and wanted a way out. After the 2018 election that had grown to 86 percent.

A lot of people are miserable, and that's a good thing. They may be motivated to do something else.