Democrats were meant to take heart from a poll released earlier this year showing that Chris Christie, the Republican governor of New Jersey, could be beaten by the right opponent.

But the poll (conducted by Democratic firm Public Policy Polling) was not exactly a repudiation of Christie's policies. The one Democrat who could beat him: Cory Booker, the mayor of Newark, New Jersey's deeply distressed largest city, who happens to agree with much of the Christie program.

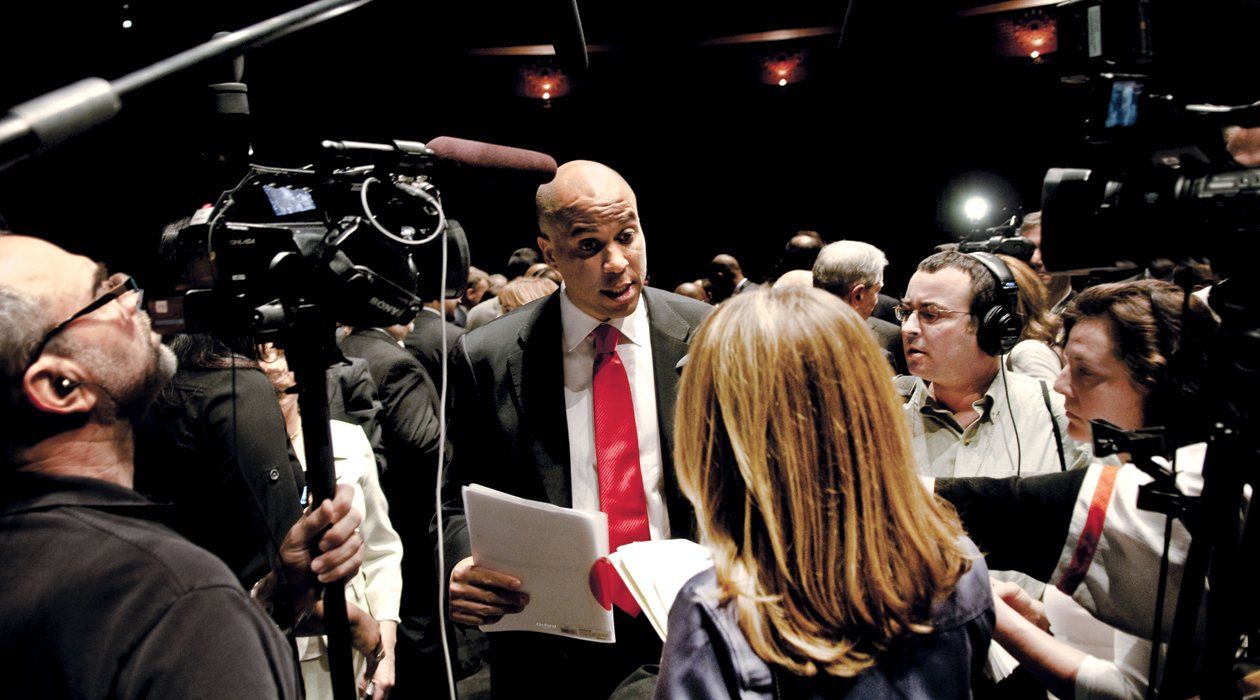

The Booker-Christie alliance—they communicate nearly daily by telephone or text—is one of the more intriguing friendships in politics and one that is not necessarily embraced by their respective fiefdoms. "There are people in his camp, and I know there are people in mine, who are not really happy about that," Booker says. "People would rather predict a 2013 political contest between us. But the one thing I have to say about the governor is that he is really interested in solving problems."

From his vantage point in gritty downtown Newark, Mayor Booker has watched Christie's rise with a mix of amusement and admiration, although the former prosecutor's approach occasionally strikes Booker, the conciliatory community organizer, as a bit too aggressive. "I try to stay away from critiquing the governor's style," he says, "but sometimes I'll cringe a little bit about the way he'll go about engaging certain people or certain factions."

Booker, who at 41 is seven years Christie's junior, grew up in the prosperous, mostly white New Jersey suburbs, played tight end at Stanford before studying at Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, and earned a degree from Yale Law School. Arriving in Newark in 1998 on a personal mission to rescue the city, which had become a national symbol of urban decay and corrupt bossism, he was an outsider who favored a politics of opportunity over that of grievance and entitlement.

Communion with Christie is practical as well as philosophical. His first priority when he entered office in 2007 was to curb Newark's violence, and he largely succeeded. His abiding goal, though, is to rescue Newark's wretched schools, which had so badly failed the community (the system was incompetent and corrupt, with principalships being bought and sold, and only one in four students passing proficiency tests) that the state had taken them over in 1995. Booker ached to try some of the school reforms that showed promise elsewhere, from charter schools to vouchers, but local interests opposed those ideas and Democrats in the state capital in Trenton were not inclined to intervene. Christie has proved a willing advocate, with nothing to lose by alienating Newark's reform resisters. "I often joke that he got six votes out of the city of Newark," Booker says cheerily. For Christie, meanwhile, it has been useful to have an ally in the state's largest, almost entirely Democratic, city. Booker goes as far as to suggest that his and Christie's mutual good will was instrumental in Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg's announcement last fall that he would contribute $100 million to Newark's school reform.

Booker sees in Scott Walker, the Republican governor of Wisconsin, an ideological opportunist; but he also worries that Democrats, in reflexively defending the status quo, are ceding the critical issue to Republicans. "The Democratic Party needs to be communicating this issue in a humane way that is about bringing our nation into a new era—an era that is affecting the policies of Spain and Greece, as well as California and New York."

Booker notes that some Democrats are now beginning to find their voice. When he listened to New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo's inaugural speech, "it sounded very like the inaugural speech of Chris Christie," he says. "I'm hopeful that people are beginning to recognize the gravity of the crisis we're in. But we're nowhere near a national awakening."

That outlook may influence Booker's choices about his own political future. He indicates that he is leaning toward running for a third mayoral term in 2014, partly so he can oversee the school-reform program galvanized by Zuckerberg. Popularity polls aside, the more he learns about the severity of the problems facing New Jersey, the less sure he is that he would want the state's top job. He recently ran into a top Democratic fundraiser, who urged him not to run. "I'm very familiar with our state's pension problem,'" the moneyman told Booker. "And what Governor Christie is doing is not enough."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.