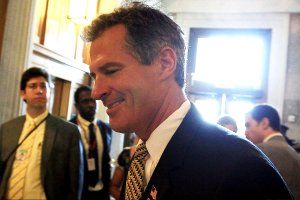

This is what anticlimax is all about. The final vote tally in the Senate on the historic financial-regulation bill Thursday was 60 to 39, but in its final weeks, this drama—a term one must use loosely—was almost entirely about political maneuvering behind closed doors. And in the strange Alice in Wonderland way that single senators can grow suddenly all-powerful on the Hill, the biggest winner in the end might well be the most junior member of the Senate, Scott Brown of Massachusetts. As one of the very few Republicans willing to cross lines and vote to end debate, Brown had enormous leverage that he used brilliantly. Brown ably represented his state's major financial firms, State Street and Fidelity, which in turn had the rest of Wall Street depending on their every move by the end. So perhaps the "Dodd-Frank" legislation ought to be known henceforth as "Dodd-Frank-Brown."

"I'm grateful that a few brave Republicans are doing the right thing for our country," Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid said just before the cloture vote, referring to Brown and Maine's Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins. But bravery seemed to have little to do with it, not when Brown came away with major victories for his wealthiest constituents. He managed to dramatically weaken the "Volcker rule" barring banks from speculative proprietary trading, proposing a 2 percent exemption (which conference chair Sen. Chris Dodd then generously raised to 3 percent), and he got the Democrats to quash a planned $19 billion rainy-day tax on banks as well. Thanks in large part to the former male model from Massachusetts, said Sen. Ted Kaufman of Delaware, "The overarching problem is that banks will continue to be able to offer and run—never mind partially own—risky investment funds." One would hope Brown's campaign coffers are even now overflowing from financial-sector donations.

The end result, which President Obama will sign into law shortly, does many good things: it brings trillions of dollars in "dark" trading in over-the-counter derivatives into the open; it creates new, tough watchdogs for credit-card and mortgage companies as well as banks; it gives the government new tools to liquidate failing firms; and it curtails the Section 13.3 Federal Reserve law that allowed the massive bailouts of the last two years. But as Senator Kaufman, one of the strongest holdouts, said "while holding his nose" and voting in favor of cloture, the vast 2,400-page bill still leaves most of the important decisions unresolved. Almost all of those decisions will be made by regulators over a period of years in closed rooms, out of the headlines.

"It is estimated that various federal agencies will be charged with writing over 200 rulemakings and dozens of studies," said Kaufman. "Many of the same regulators who failed in the runup to the last crisis will once again be given the solemn task of safeguarding our financial stability. Like many others, I am concerned whether they have the capacity and wherewithal to succeed in this endeavor."

The work of the banking industry—and legislators—is not yet done.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.