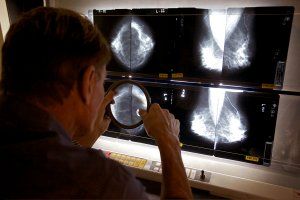

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), the precursor to breast cancer, is identified much more often today, thanks to advances in imaging technology. But getting this diagnosis exactly right remains difficult. It's not always easy for even expert pathologists to differentiate between normal cells and the tiny precancerous cells that may cluster in a woman's milk ducts. These noninvasive cells represent such an early warning of cancer that they are known as stage zero.

That's why, as an article on the front page of The New York Times reported yesterday, too often, women mistakenly diagnosed with DCIS have undergone disfiguring surgery and radiation to treat a cancer they never actually had.

So what's the take-away message for women who want to avoid similar mistakes?

Understand that it can be challenging, even for experts in breast pathology, to get a DCIS diagnosis precisely correct. Cancer develops along a continuum that stretches from normal cells to aggressively invasive cells. "It's not like you're crossing a railroad track and the bar is either down or it's not," says Dr. Charles Loprinzi, professor of breast-cancer research and a coauthor of the Mayo Clinic Guide to Women's Cancers. "There are shades of gray."

Even when doctors have correctly diagnosed DCIS, they often disagree about the kind it is because of very subtle differences in the patterns and structures the cells form. Pathologists like Dr. Ira Bleiweiss of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, who specializes in breast cancer and does hundreds of consultations a year, says that about 40 to 60 percent of the time, he doesn't agree entirely with the initial diagnosis. But, he adds, the difference of opinion is usually relatively minor and the treatment recommendation typically remains the same (such as removal of some more breast tissue). However, he says, in perhaps 10 percent of the cases, the difference is big enough to result in a different treatment strategy, and in less than 5 percent of cases, he sees a blatant error and changes a malignant diagnosis to a benign one (or vice versa).

To reduce the odds that you're misdiagnosed, start by asking about the credentials of the pathologist who first reviewed your results, and whether he or she is a breast specialist. The College of American Pathologists is preparing to certify pathologists who review at least 250 breast biopsy results a year.

Proceed slowly. While quick action is sometimes required for a breast-cancer diagnosis, women who are told they have DCIS usually have at least a few weeks to double-check that the diagnosis is accurate before they have to make further decisions. "There are a lot of women who hear this diagnosis and say 'I want you to take it out right away. I have a 2-year old who I want to see grow up,'" Loprinzi said. But there is usually no reason to rush toward surgery or radiation.

Get a second opinion on your initial biopsy results from the best-qualified expert you can find. There are a limited number of pathologists who specialize in giving second opinions on breast cancer. Find one. Many are at medical centers affiliated with major academic institutions or large diagnostic centers. National and local breast-cancer support groups can help you find good referrals.

If there is no such specialized pathologist in your area, pathology slides can be mailed. To help the pathologist make the most accurate diagnosis possible, it's a good idea to send a copy of the radiologist's report as well as the X-ray he or she took of the core specimen after the biopsy. Some pathologists also like to review the mammogram films. Looking at all the data is sometimes necessary to get the diagnosis precisely right, says Bleiweiss, who is a professor of both pathology and oncological sciences, as well as chief of surgical pathology.

While some women diagnosed with DCIS will never go on to develop invasive breast cancer, there is currently—and, unfortunately—no reliable way to determine who will and who won't, or how quickly it will progress. What doctors do know is that there are multiple types of DCIS, including low grade, intermediate, and high grade. If low-grade DCIS evolves into cancer, it will likely be low-grade invasive, and may never be deadly. But high-grade DCIS is likely to become the more dangerous high-grade invasive over time. Knowing what kind you have, and considering things like your age and other medical conditions, will help you make an informed decision about treatment.

Talk to several specialists before you decide on the type of surgery, the need for radiation, and follow-up care. While the standard way of proceeding is to remove the abnormal cells, radical surgery is rarely recommended in these cases.

In the meantime, research continues. There's hope that in the future, drugs may be able to suspend or stop further progression of these cells and surgery will become less common. But in the short run, it would be extremely helpful if more pathologists were trained to be specialists in this area—and funding such fellowships should be a priority for breast-cancer philanthropies.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.