Mark Twain is surely America's best-known author. It is tempting to say he is also the country's favorite writer, but that can't be true. Too many grandparents have given too many copies of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer or The Prince and the Pauper to too many grandchildren, who then went about for the rest of childhood under a cloud of undischarged obligation while those books sat on numberless shelves, unread. If that didn't finish off any appetite for Twain, there was always the high-school ritual of force-feeding The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Lucky the adolescent who lives in a school district that has banned Huck. There is nothing like a banned book to turn a teenager into a devoted reader.

All that pales, however, beside the worst crime ever committed against children in the name of Twain: the Claymation version of No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger. In this 1986 film, Twain's nihilistic little novel gets boiled down to a brief episode in a movie that also extracts material from several other Twain works, including Tom Sawyer and Letters From the Earth. But The Mysterious Stranger outdoes them all. In less than five minutes a Claymation Satan visits with Tom, Becky Thatcher, and Huck; builds them a village; then destroys it with lightning and an earthquake that swallows up all the cute little clay villagers, farmers, soldiers, and one particularly pitiful cow. It is altogether terrifying. One can only shudder at the thought of countless impressionable, unsuspecting children curled up in front of the television and being scarred for life after blithely stumbling across this ink-dark work. Anyone who thinks that there is no such thing as too much Twain has not seen it. Sometimes you truly can take a good thing too far.

The Claymation Stranger doesn't have much in common with Twain's story except for its nihilism. But it's the best possible proof that you shouldn't foist Twain off on the young just because he wrote books with children in them. If you take Twain for granted, if you think he's nothing but a kindly, harmless old gent (and even more harmless for being dead), you're not only wrong—you're going to get hurt. A dead bee can sting you and, even from the grave, Twain still knows how to sting.

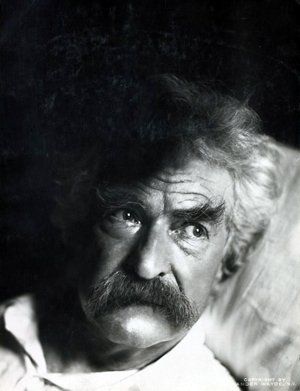

When he was alive, Twain was well known twice over—as a monologuist on the lecture circuit and again as a writer. His life and work have inspired dozens of plays, movies, television specials, puppet shows, and at least one Broadway musical. And yet, while no American author may be better known, none is more elusive. Every time you think you know him, you read something new that rearranges your opinion. Did the same man really write Huck and Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc? Did the author of Tom Sawyer, one of the sunniest books in our literature, also write No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger, one of the darkest? The more you read, the more complicated he seems.

Now we must get reacquainted all over again. In November the University of California Press publishes the first installment of Twain's three-volume autobiography. This edition will be nothing like the previously published versions cobbled together by the author's editors and executors after he died. Instead, for the first time, it will be the autobiography he wanted—a disorganized, almost stream-of-consciousness set of recollections unlike any memoir ever seen, but pure, uncut Twain from start to finish. (For a sample, check out the hilariously subversive excerpt on page 41.) Just don't think that this settles the issue of his identity. On the contrary, as delightful as it is, the autobiography only compounds his protean elusiveness. He is still a mystery, a riddle wrapped in an enigma shrouded in a white suit.

The mystery begins with what to call him, Mark Twain or Samuel L. Clemens? In his 1966 biography Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, Justin Kaplan exploited the dichotomy and tension suggested in the author's double name, exploring how the proper Hartford, Conn., burgher and the frontier lord of misrule managed to coexist under the same hat. Kaplan's thesis was right there in his title—not "or" but "and." Twain was a man of parts, and not many of them from the same kit. It's no wonder he's inspired at least 25 biographies. Albert Bigelow Paine was at work on the authorized life before Twain died. This year, timed for the centenary of that death, there have been four biographies already. Only Jerome Loving's is a full-scale life. The other three deal with parts, one with Twain's early manhood and two on his last days (even a book about his dotage is fascinating). The Library of America has also just published an anthology of notable authors, including his contemporaries and ours, writing about Mark Twain. And most recent is the oddest of all, Andrew Beahrs's absorbing Twain's Feast, which explores 19th-century American food using Twain's culinary prose as a touchstone. Would Twain like being thought a foodie? No telling, but he might not have liked any of them. He was touchy and he knew how to nurse a grudge. That said, he also liked being the center of attention, so, like Tom Sawyer attending his own funeral, he would have avidly read them all, with anger and pride.

Twain is remarkable several times over. He was a self-invented prose stylist, a fantastically failed businessman, and one of the few writers of his time willing to directly address the evils of slavery and racism. But surely the most remarkable thing about him is that he is still funny. How many of us can name another comic writer or a humorist who's been dead for a century? Even readers who know Hawthorne and Dickinson couldn't pick their comic contemporaries Petroleum V. Nasby or Josh Billings out of a lineup. Most comics' material dies before they do, but Twain's humor stays surreally fresh. For his debut on what was then known as the lecture circuit, in San Francisco in 1866, he had the handbills printed to read "Doors open at 7 1/2. The trouble will begin at 8." Call it a threat or a promise, but he made good on that claim all his life. He's still making good on it.

He once drew close distinctions between humor (American), comedy (English), and wit (French), but he could do them all. We still quote his one-liners. "Man is the only animal that blushes. Or needs to." "Nothing is made in vain. But the fly came near it." "It is the foreign element that commits our crimes. There is no native criminal class except Congress." "Patriot: The person who can holler the loudest without knowing what he is hollering about." Somehow he found the knack of being both funny and profound at once, like Henny Youngman with gravitas.

His comic fiction depended less on jokes and more on situation and character, and it, too, comes without an expiration date. Tom Sawyer's fence-painting scam is known to people who have never read a line of Twain. Huck Finn will live as long as Falstaff. As for wit, this may be where the true Twain genius lies. It was not what he said or wrote, but how he put it. He could be deadpan on the page, in one sentence after another where he seems to be proceeding straightforwardly, and then, without warning but with perfect timing, he hangs a sharp left and the sense of the passage turns upside down. In Following the Equator, his jeremiad against colonialism fitfully disguised as a lighthearted travel book about circling the globe, he writes of his keen anticipation of seeing the Southern Cross for the first time. "Judging by the size of the talk which the Southern Cross had made, I supposed it would need a sky all to itself. But that was a mistake. We saw the Cross tonight, and it is not large … It is ingeniously named, for it looks just as a cross would look if it looked like something else."

Twain can seem like many things—wisecracking country boy, your favorite crusty old uncle (the one who taught you how to play poker), the sublime poet of the Mississippi. But it's his humor, more than anything, that makes him seem like a friend, a contemporary, maybe not anyone you know but someone you wish you knew. Humor is famous as a leveling device, but it doesn't just cut its subjects down to size. It makes democrats and equals of us all. You can't be funny and talk down to people. So, when you read either of his two masterpieces, Huck and Life on the Mississippi, you always have the sense of being in the same room and on equal footing with the author. And when he really gets going, you're right there on the river with him. This sense is so overwhelming at times that it is surprising, upon looking up from the page, to find yourself alone. When it came to putting the human voice—an American voice—on the page, he had no peer. And no one, on or off the page, was better company.

Ernest Hemingway claimed that "all American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn." It may be even more accurate to say that all American humor comes from Twain as well. His example paved the way for Will Rogers, James Thurber, Richard Pryor, Lily Tomlin, and Jon Stewart—droll outsiders, one and all, who invite us to join them in the back of the class, where school is always out and everyone is free to mock whatever party line is being preached at the moment. There was nothing like that in America's humor before Twain. After him there is not much else.

It would be reductive to say that humor was Twain's shield against the world's absurdities, because humor is not an accessory and because he was funny right down to the marrow. But the humor did coexist within him with a multitude of other impulses. Like the sunniness in his books that is always giving way to darkness—or barely concealing it—his humor forsook him now and then, especially as he grew old, and in its place there is deep sadness and a bottomless reservoir of rage.

The calamities and tragedies that clouded the last quarter century of his life—bankruptcy, the deaths of two daughters and his wife—blackened his vision but they did not still his pen. Writing for Twain was second nature—his way of dealing with the world. His novels, travel books, stories, essays, and letters fill not merely several volumes but several shelves. Amazingly, new material still comes to light at a steady clip. In the last 50 years, more than 5,000 letters have surfaced. According to the staff of the Mark Twain project at the University of California, Berkeley, an average of two new letters appear every week. Last year saw the publication of Who Is Mark Twain?, a volume of 24 unpublished Twain pieces. When the paperback edition came out this spring, two new stories were added.

While still in his teens, he began keeping notebooks. The first was a log of the Mississippi River in which he, as an apprentice steamboat pilot, recorded every bend, every sandbar, every farmhouse, doghouse and outhouse along the banks, anything that would orient him while piloting. That logbook was nothing but data, but the recording habit stuck. In little leather-bound notebooks that he carried with him all his life, he set down dialogue he overheard, story ideas, weather conditions, anything that caught his fancy. Words were a compulsion with him, and not just any words. "The difference between the almost right word and the right word," he wrote, "is really a large matter—it's the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning."

He did stop finally, four months before his own death, when his daughter Jean died after an epileptic fit on Christmas Eve 1909. For three days, straight through Christmas, he wrote of Jean's death, trying to process the event, and if America has a Shakespeare who was his own Lear, the proof can be found in those pages.

"I lost Susy thirteen years ago; I lost her mother—her incomparable mother!—five and a half years ago; Clara has gone away to live in Europe; and now I have lost Jean. How poor I am, who was once so rich! … Jean lies yonder, I sit here; we are strangers under our own roof; we kissed hands good-by at this door last night—and it was forever, we never suspecting it. She lies there, and I sit here—writing, busying myself, to keep my heart from breaking. How dazzlingly the sunshine is flooding the hills around! It is like a mockery.

"Seventy-four years old twenty-four days ago. Seventy-four years old yesterday. Who can estimate my age today?"

He said it was the last thing he would write and that it would end the autobiography that he had been dictating for several years. Like almost everything he produced, it transcends form, being part valedictory, part eulogy, and a brooding, raging cry against an indifferent heaven. It is the testament of a man who has finally given up on life, and to call it beautiful seems almost beside the point. Twain meant to impress no one with that essay. Still, it is worth noting that, faced with an event that would have paralyzed most people, his first reaction was to reach for his pen and attempt what he had always done so successfully in the past—to write his way out of trouble.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.