Water Worlds

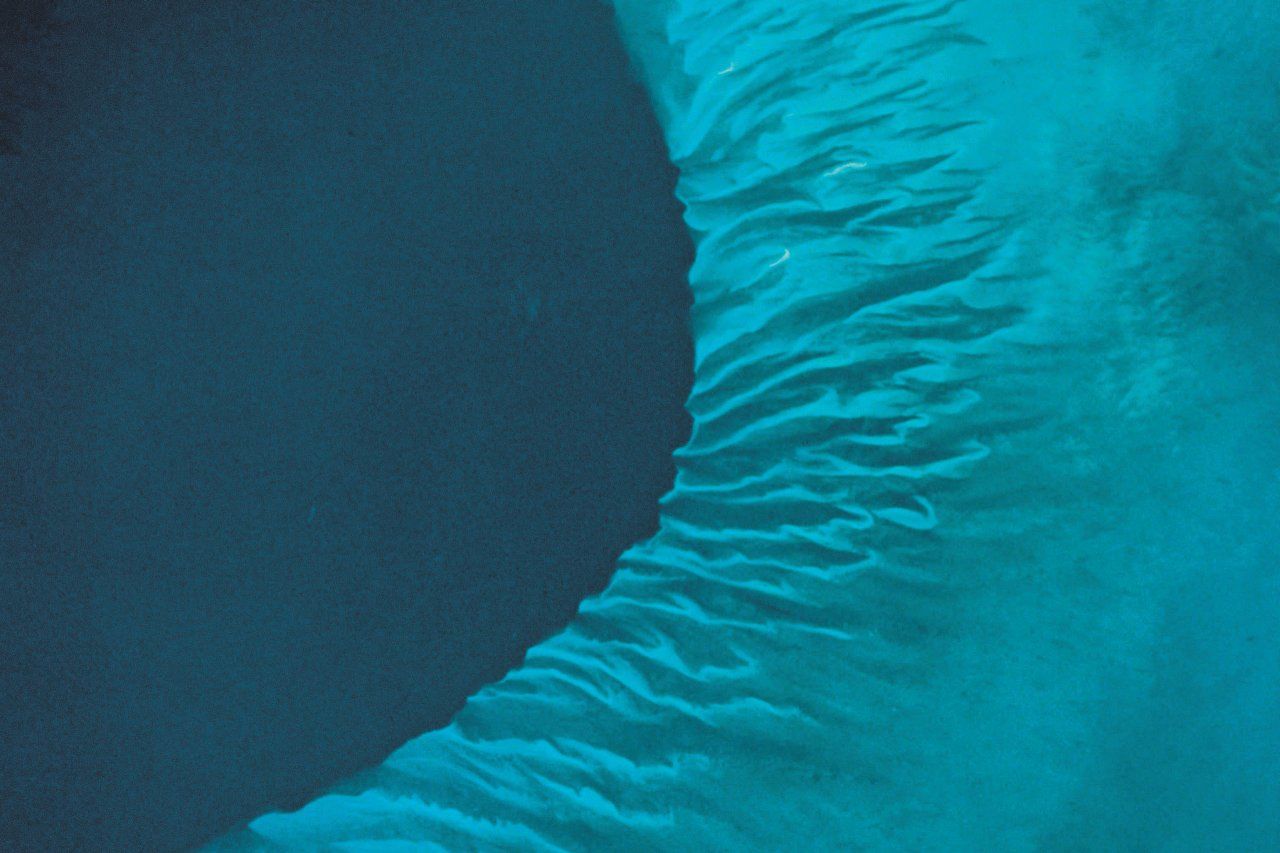

Earthlings learned to think of their planet as the tiny azure dot in the vast blackness of space first photographed by astronauts in the 1960s. It seemed the only lonely blue planet in the universe. No more. In April, NASA announced that its Kepler space telescope had discovered five planets circling the star Kepler-62, some 1,200 light-years from Earth. Researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics then reported that their calculations showed two of those planets, dubbed Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f, are covered entirely with water. They are too small and far away for visual contact, even though they are bigger than Earth. What's known is based on data collected when their orbits take them in front of their sun, which is a little smaller and cooler than ours. But after so many decades speculating about life on the other, desert planets of our own solar system, where finding bacteria would be a stunning breakthrough, suddenly scientists are speculating about complex life-forms, even civilizations. These planets "have endless oceans," says researcher Lisa Kaltenegger: "beautiful, blue planets circling an orange star." Given what she calls "life's inventiveness," she imagines beings there might even have developed technologies.

Giving Language the Finger

If Johnny can't spell, don't blame his thumbs. According to Columbia University linguist John McWhorter, concerns that texting will undermine literacy are misplaced. There was always a division between our casual spoken language and formal written discourse, says McWhorter, and texting is not so much a new way of writing as a new way of talking. He calls it, for want of another term, "fingered speech." In a recent TED Talk (which was, of course, both written and spoken) the author of Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue makes the point that professors have been lamenting the mediocre-or-worse composition skills of young people at least as far back as the first century A.D. It's much more interesting, he suggests, to look forward and watch the evolution of this new hybrid means of communicating. "What is going on is a kind of emergent complexity," he suggests, with new structures as well as new words. LOL, for instance, has evolved from "laughing out loud" to a more generalized "marker for empathy," like, "lol we're in this together." McWhorter sees it all as a positive expansion of a kid's linguistic repertoire, almost like learning a new dialect ... lol.

Transparent Thinking

The image of a whole brain has been rendered before from bits and pieces, whether illuminated by radiology or cut into slivers with cold steel blades. But chemical engineers and neuroscientists at Stanford University have now developed a process that renders the organ of thought quite literally transparent. To be sure, the technique called "Clarity" has been used thus far mainly to study postmortem mouse brains, but testimonials already are accumulating. Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, says the process "transforms the way we study the brain's anatomy and how disease changes it." He claims that "in-depth study of our most important three-dimensional organ" will no longer be "constrained by two-dimensional methods." Team leader Karl Deisseroth says the process may eventually be applicable for research on many kinds of tissue and "any biological system." The innovation is the replacement of fatty cells called lipids, which make the brain opaque and obscure its dense neural connections, with a substance called hydrogel, which is transparent. The "clarified" brain, as the Stanford team calls it, can then be treated with fluorescent dyes that light up specific circuitry. The detail is extraordinary, right down to the molecular level.

News Gathering

National Early Warning Systems (NEWS) are now fairly well advanced in most developed countries, giving both urban and rural populations at least some early word of impending disasters. But in much of the rest of the world, vital information is often hard to come by if, indeed, it comes at all. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, landslides, floods, droughts, and crop failures arrive unpredicted, as far as most people on the ground are concerned, and with devastating impact. The toll taken in the overcrowded cities and slums of developing countries is especially brutal. So the World Economic Forum is proposing the creation of a "network of networks" that will pull together the scattered elements of warning systems that do exist and knit them into a web the WEF is calling a "public-risk Internet." This would go far beyond the most extensive operation to date, the narrowly focused tsunami-detection network in the Pacific. The costs would be shared as well as the information, which would provide important data to researchers looking for ways to soften the effects of the disasters. Until that happens, in much of the world no NEWS is very bad news indeed.

All Things Bright and Beautiful

There are today roughly 1.9 million known species of living organisms on Earth. But from trilobites to passenger pigeons, countless numbers of species have disappeared, and lately some scientists have been cobbling together the genetic fragments necessary to try to resurrect a few. Before we bring back the wooly mammoth, however, argues William Y. Brown at the Brookings Institution, it would make sense to make sure we've preserved genetic material for every living thing that's still left. In a wonderfully reasonable proposal he published in The Wall Street Journal, Brown called for the creation of a "Noah's Ark" for species DNA. In effect, he wrote, the genes would be stored in "genetic libraries for research and commerce and for recovery of species that are endangered." Several institutions have partial collections. The American Museum of Natural History in New York, for example, keeps 70,000 cell samples in liquid nitrogen. But these are just a fraction of what's needed. Fortunately, it's not a very expensive proposition by modern governmental standards. Brown calculates the total price for preserving the DNA of all known species on the planet at less than half a billion dollars in initial cost, and about $1 a year per species after that.

The Leaning Tower of Ivory

Lambasting "eggheads," "pinko professors," and "pointy-headed intellectuals" is a tradition as old as American populism, and one that many a modern conservative has embraced. The Tea Party darling from Texas, Sen. Ted Cruz, once claimed that when he was at Harvard Law there were 12 Marxist professors who wanted communists to overthrow the American government. That was stretching the truth. But a new study concludes there's really not much doubt the Ivory Tower leans to the left. "Between 50 percent and 60 percent of American professors can be classified as some version of liberal," writes Neil Gross, author of Why Are Professors Liberal and Why Do Conservatives Care? The essential reason is less conspiratorial than cultural. In a country where there is widespread respect for higher education, but generalized suspicion of intellectuals—particularly the left-leaning kind—the groves of academe have offered a refuge. But Gross finds scant evidence that professors indoctrinate their students with radicalism. The more subtle problem: conspicuously left-wing profs offer easy targets for right-wingers who want to slash the budgets at state universities or discredit as "liberal bias" scientific findings in such vital areas as climate change.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.