Rights for Robots?

Many sci-fi films have raised the question of whether robots, in some distant future, will have rights. But Kate Darling at MIT thinks the question is current already. She argues that robots like Pleo the Dinosaur become companions much like pets, and that when people relate to them, they want to protect them. In one recent "robot ethics" workshop she conducted, none of four groups could kill their Pleo. Of course, it's really more about us than them. "If we can see the emotions that we know in ourselves in the other object—or being—that is when we start to feel protective," Darling says. Even when it comes to a living animal's rights, she notes, "the cuter it is, the more it stimulates emotions." The quintessential example so far is Paro, a white, furry $5,000 robot baby seal used for hospital therapy. (Yes, it looks just like the ones that hunters in Canada bludgeon to death, to the horror of animal-rights groups.) Dementia patients find Paro's purring as soothing as a live animal's. No one would want to see it mistreated. "Over the next decade, we're going to see a lot more toys like that," says Darling.

The Economics of Love

Valentine's Day came and went without a major impact on economic policy. But it got Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers thinking. After examining the data in a Gallup survey of 136 countries, which asked respondents, "Did you experience love for a lot of the day yesterday?" they posted a brief essay on a Brookings Institution blog. (Wolfers is a senior fellow there.) "Love is valuable, even if it is absent from both our national accounts and our political discourse," they wrote. "In the language of economics, love is a form of insurance." It provides both a psychological sense of security and real material security. "This is why the household remains one of the most powerful institutions for organizing not just families but also our economic lives." (The authors were not arguing for gay marriage, but you can see how the logic would apply.) "When you expand the boundaries of trust and reciprocity," say Stevenson and Wolfers, "you expand the boundaries of what is possible." In case you were wondering, the people of the Philippines and Rwanda (interestingly) are at the top of the much-loved list; the United States ranks 26; France is 57; Israel is 88; and at the very bottom, Armenia.

America to the Rescue

Two scholars writing for the Council on Foreign Relations argue that the United States should have specialized combat units ready to stop genocide and other atrocities. One example, according to authors Stewart Patrick and Micah Zenko: "The Army's 82nd Airborne–Ready Brigade can deploy as many as 3,600 troops anywhere in the world within eighteen hours notice." But as the paper notes, "military officials demonstrate little enthusiasm" for this idea. After the shock of genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda in the 1990s, many politicians vowed never again. But given the sad saga in Iraq, the problematic outcome in Libya, the Syrian charnel house, and the uncertainties that lie ahead in Mali, it's hard to get soldiers excited about the right to protect (R2P in NGO jargon). So an estimated 250,000 people continue to die in armed conflicts every year, and the World Bank puts the economic costs at "upwards of $100 billion." Much more needs to be done at the international level, say Patrick and Zenko, but they also want the Obama administration "to provide specific guidance to the military in its National Security Strategy to plan and train its rapidly deployable forces for genocide- and mass-atrocity-prevention missions."

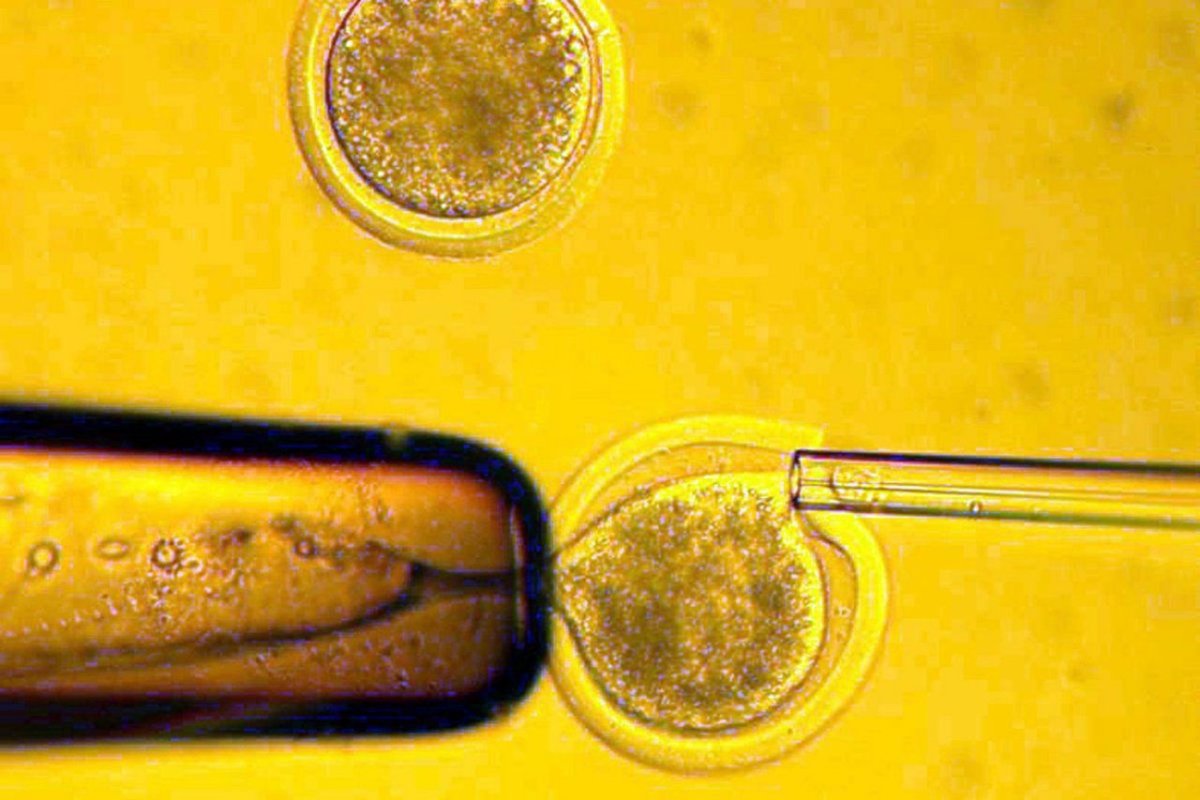

Printing with Stem Cells

When a group of researchers in Scotland published a paper recently showing how they used a special two-nozzle computer printer filled with "bio-ink" to make 3-D objects out of human-embryo stem cells, speculation ran wild that they may soon be printing whole human organs. But, as often happens, the excitement exceeded the experiment's actual results. All they've created so far are tiny "spheroids," as they call them. The breakthrough was finding a way to create any shape at all while keeping the cells viable. If the technology is perfected, on the other hand, it could revolutionize surgery. The first stage of development will be to create tissue on which drugs can be tested for toxicity. Will Shu, one of the researchers, says that they also expect the printing technology can be used in laparoscopic or keyhole surgery, where the tiny nozzle "can be guided by an endoscope to deliver cells to where they are needed for repairing tissues and organs inside the body." That's still a few years away, and ethicists who have problems with the whole idea of stem-cell research may find the subject distasteful. Those whose lives are saved probably will not.

The Global 0.00001 Percent

Conspiracy theorists may wax ecstatic about the findings of three researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. They looked at the enormous control over the global economy exercised by multinational corporations and, after examining 43,000 companies, concluded that 737 top shareholders (institutional as well as individual) can control 80 percent of these corporations' value through their various ownership networks. As a portion of the world's population, by our calculation, that would be, oh, about 0.00001 percent. But James Glattfelder, one of the authors of the study and a theorist of complexity, says he doesn't believe there's a conscious conspiracy. A better analogy may be flocks of starlings or schools of fish that swirl and shape and reshape in response to all sorts of stimuli, often unpredictably and sometimes with catastrophic results. For the global economy, this huge concentration of control is a systemic risk, Glattfelder said in a recent TED talk, and recognizing this fact is not a matter of ideology. "We need to move away from dogma," he said. But if the bottom line involves the 0.00001 percent sacrificing some of their wealth and influence, that may be very hard to do.

A Bright Idea for Back Roads

Simple ideas, if they work, can have big consequences. The Dutch are developing what they call "smart highways" that use a minimal amount of energy but give drivers a much clearer idea where they are going. And they couldn't come at a better time, with hard-pressed governments all over Europe shutting down streetlights to save money. One innovation is photoluminescent paint that absorbs energy from the sun during the day and then shines it back all night as the center stripe on roads or along the edges. Other overlays will show enormous snowflakes when the pavement is freezing. "The road knows, 'I am warm; I am cold; I am safe; I am not safe,'" says designer Daan Roosegaarde, known for imaginative approaches to sustainability. (Another project: a dance floor that generates enough electricity to run a club's lights and sound system.) The first smart-highway prototypes will be installed in the Dutch province of Brabant in the next few weeks. But Roosegaarde says the glowing paint is just the beginning: he's drawing on a list of 20 ideas that include pinwheel generators for roadside lights and electrified lanes that can recharge battery-powered cars as they drive on them.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.