It was the Fourth of July in America, but in Paris a different sort of spectacle was unfolding. Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of the French conglomerate LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton), took his place of honor in the front row of an elegant tent in the courtyard of the Musée Rodin, where he presided over the start of the fall haute-couture fashion week. The late-afternoon show was the most highly anticipated of them all: Christian Dior, one of Arnault's many brands and one that in recent months was rocked by scandal.

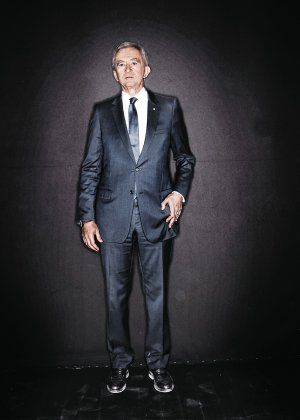

In public, Arnault, 62, is controlled and dignified, tall and trim, with a broad forehead and boyishly unruly gray hair. His English is thickly accented but precise. In business, he is known for being both aggressive and stealthy. And he is not prone to displays of emotion. At the Dior show, he was accompanied by his son Antoine—who looks like a younger, less burdened version of his father—and his daughter Delphine, a slender blonde with her father's high forehead. France's former first lady Bernadette Chirac sat nearby.

Established in 1947, Christian Dior is considered France's most prestigious label. Its founder was credited with reviving the country's stagnant fashion industry after World War II with a single collection of lush skirts and wasp-waist jackets that came to be known as the "New Look."

Over time, the brand captivated Princess Diana, who popularized the Lady Dior handbag with its quilted body and dangling CD charms. Today it's a darling of red-carpet butterflies and is the de facto couturier of French first lady Carla Bruni-Sarkozy.

The Dior show tried to conjure that storied legacy. But as soon as the lights dimmed and the first model emerged, the Twitter universe exploded with fashion commentary, most of it negative—and understandably so. This fall collection was an '80s-inspired kaleidoscope of chaotic colors, awkward ball gowns, ungainly architectural silhouettes, and even a puzzling homage to the clown Pierrot, complete with pointy little hat.

When it was over, the virtually unknown atelier director, Bill Gaytten, and his first assistant, Susanna Venegas, stepped out and gave the audience a wave.

Haute couture, the craft of handmade garments, is supposed to be the pinnacle of fashion—the concept car of the garment business. This show was meant to be an expression of a couturier's most dazzling, singular vision—clothes as they could be. But such virtuosity was missing.

And all because the great French fashion house is in limbo.

For nearly 15 years, John Galliano served as creative director of Dior. He was a whirlwind of outré ideas and ruckus-raising controversy, and Arnault reveled in Galliano's audacity. The designer's runway bows rivaled his collections in imagination and swagger. The tent would go black and the lights would flash as if to herald the arrival of a rock star. As the music built, Galliano would strike a catalog-model pose. He'd linger on the runway, allowing his star power to radiate outward.

The designer—musclebound, with a face out of a Toulouse-Lautrec painting—summed up what luxury fashion had become at the hand of Arnault: an industry driven by flamboyant stars, glittering brand names, and hype.

But then Galliano crashed to earth in March, after allegedly spewing anti-Semitic insults at a couple in a Paris bistro. Hate speech is illegal in France, and soon he was fired and shipped off to rehab. On June 22, when Galliano showed up in court, he was a beaten man who confessed to multiple addictions and claimed no recollection of what came hurtling from his mouth. A verdict is expected in September.

Arnault, meanwhile, must reinvent Dior. At first blush, it seems not such a tall order for the most powerful man in the global fashion industry. He is also the wealthiest man in France—Forbes estimates his worth at $41 billion—and controls luxury labels ranging from Dior and Louis Vuitton to Donna Karan, Céline, and even Galliano's own signature label (from which the designer was also dismissed). Arnault's empire extends from New York to Mongolia and includes the airport retailer DFS, Sephora cosmetics stores, and even Dom Pérignon.

His decisions carry enormous influence, and they are often imitated. He reordered the fashion universe in the 1990s when he hired New York's downtown hipster Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton. Jacobs unleashed monogram handbags in colorful Takashi Murakami prints and Stephen Sprouse graffiti. The era of the "it" bag was born. Arnault brought Alexander McQueen to Givenchy, helping to propel him into the international fashion limelight. And, of course, he hired Galliano.

Arnault's philosophy of merging subversive talent with dusty, historical brands became the subject of a Harvard Business School case study and the corporate blueprint for reviving stagnant fashion companies, from Yves Saint Laurent to Rochas. He arrived at the pinnacle of fashion through buyouts and mergers and occasionally through bruising takeovers, only one of which—Gucci—he has lost thus far. His expansion of LVMH has been a model for other luxury conglomerates.

Arnault, who prides himself on managing creativity—on giving it room to be disorganized and spontaneous—took Galliano's meltdown personally. "I'm surprised that I did not get a call or a word of excuse from him," he told me not long after Galliano's banishment. "After all that I did for him?"

Forgiveness has not been forthcoming. "Not yet," Arnault said.

Galliano's alleged hate speech was an assault on Arnault's beloved Dior, the first luxury label he acquired and the one he watches over with the greatest care. The behavior also called into question Arnault's long-held strategy of hiring rakish and unpredictable designers to create star brands.

Signaling a new direction, Arnault has been going out of his way recently to spotlight the low-key craftspeople of the atelier. He is waxing enthusiastic about the philosophy of discretion that designer Phoebe Philo has brought to Céline—incremental change, not topsy-turvy innovation.

In Arnault's new reality, buzz and brashness are taking a break.

When Arnault plucked Galliano from nearly Dickensian circumstances, installing him at Dior in 1996, a supporting cast of 200 artisans already had been working behind the scenes for decades.

During a recent visit to the Dior atelier, I met Lili Nassar, a plump, brown-skinned Frenchwoman with a bashful smile who has been at Dior for 38 years. She came to Paris from Africa and studied at the Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture, which produces the country's skilled seamstresses and tailors. She was only 21 when she joined the atelier, working under designers Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré, and, of course, Galliano. She has outlasted them all.

When Galliano first arrived, he had to adapt, not the atelier. He didn't sketch; his ideas were fragments in his head. People like Nassar helped coax them into reality.

"A lot of schools produce designers, but the technical people—this is what we have to protect," Sidney Toledano, the Dior chief executive, told me. "They work very hard here, and they live outside of Paris. They are not living like the designer. They are simple people. Some of them have a difficult life. They have their feet on the ground."

In short, Toledano said, "They're sustaining the house."

Arnault has great faith in the team's ability to stitch a perfect corset or jacket. That skill is at the heart of the Dior mythology—and right now, that's all he's got.

He's indebted to them for carrying on without a creative leader. "I think we have the equivalent of the Vienna Philharmonic," Arnault says. "From time to time, the Vienna Philharmonic could play without a conductor because they are so good. But that cannot last forever. We want to [make] the best choice for the house and find the best conductor."

But as the fall couture show proved, a leader is essential. Gaytten's poor reviews suggest that Dior's transition will not be as seamless as the recent one at Alexander McQueen. After that house's namesake committed suicide last year, his assistant Sarah Burton took over and has been an able, low-key successor—even shunning the attention sparked by Kate Middleton's wedding dress. When I asked Arnault about other possibilities, including his rumored interest in Haider Ackermann, he noted that the Paris-based designer with the sensual color aesthetic is talented, but his business is tiny. Could the top job at Dior be his ticket to the big leagues? "That I cannot tell you," Arnault said with a chuckle.

If any brand hints at how Arnault might solve his Dior problem, it's Céline. For years, the company was a bland purveyor of bourgeois sportswear before Philo was given free rein. If Dior was defined by bold, swashbuckling strokes, Céline is design innovation measured in millimeters. What Philo created is understatedly, exquisitely chic—without a cult of personality.

Arnault has been dazzled by Céline. It has seen triple-digit growth, according to Arnault, who believes it has the potential to be the next major brand, even in critical emerging markets like China, where many of the newly rich are still enamored of glitz. In 2010, Asia—excluding Japan—had the distinction of being the largest market for all LVMH products.

"It will take time, but [Céline] is on the way," Arnault says. "Phoebe has the potential. She is doing a style which is completely in line with our time."

And if Céline needed any further endorsement: "My daughter Delphine, she's working at Dior," Arnault says. "But she wears Céline."

(Arnault, by the way, thinks Céline isn't expensive—although a starter dress runs $2,000. "You think it's expensive?" he asks. "It's not Dior." No. But still. Bless his billionaire's heart.)

Arnault says he has no plans to transform Dior into a minimalist label. But his pronounced affection for Céline and its focus on clothes, clothes, clothes, along with his powerful appreciation for the deeply rooted atelier, raises several existential questions: Had the spotlight on a star like Galliano gotten so hot that everything else disappeared in the glare? Did it all become some overstuffed dream? Did the world lose sight of Dior's history, its vaunted craftsmanship, and perhaps even of the frocks themselves?

Arnault suggests it's time for change, time to recast his global, glittering, status-laden empire as something else. The watchwords are: intimate, Old World, artful. And the timing feels right.

During my visit to Paris, Arnault wanted me to see the rest of his empire. He showed off the picturesque L'Abbaye d'Hautvillers, home to the rarefied vintages of Dom Pérignon. And he organized a tour of his Frank Gehry–designed art foundation rising on the edges of the Bois de Boulogne.

The point of it all was that these landmarks celebrate characteristics that are the antithesis of the big-top fashion the mogul once reveled in. He's no longer bragging about that.

After all, Arnault has learned that rock-star designers come and go. "A good product," he says, "can last forever."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.