When Rem Koolhaas was born in the Dutch port of Rotterdam in November 1944, very little of the city center was still standing. The Second World War was ending but it wasn't over, and the Nazis had cut off food to the urban areas of the Netherlands, starving tens of thousands of people to death. The Dutch still remember that time as "the Hunger Winter."

"My parents needed to find extreme ways of getting food," says Koolhaas as we talk at his firm, OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), overlooking the resurrected city. "My father succeeded to buy a number of laboratory rats," he says, "and so at some point they were delivered at home, but there was no electricity anymore, so when my parents entered the apartment they felt that there was something there, and they lit a match and there was a heap, a kind of pyramid, of dead rats."

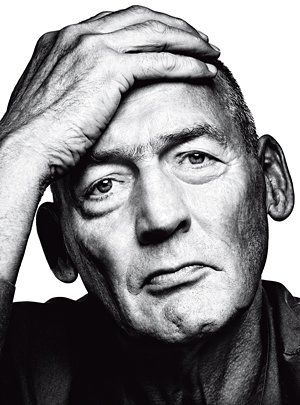

Such was the early life of one of the world's most influential urban theorists and renowned architects. In a career dense with history—his own and that of the projects he has undertaken—Koolhaas has won many prizes, including the ultimate accolade by his peers, the Pritzker, but he still comes off as modest, perhaps because Koolhaas, at 6 feet 6, has that peculiar shyness that some very tall people have.

He has designed iconic, eye-catching structures from Seattle to Moscow. And although he speaks with a Dutch accent and syntax, his written English is a torrent of brilliant staccato aphorisms. Several of his intellectual triumphs are essays on architectural trends with titles that are succinct provocations: "Delirious New York," "Bigness," "Junkspace," "The Generic City." But future generations will almost certainly think of Koolhaas in the context of one massive, monumental, contrarian, and controversial building: the China Central Television headquarters. Around his Rotterdam office, they don't call it a tower; they call it a "loop." Formally opened in May, it is built on almost 50 acres in Beijing's central business district, and its 10,000 workers are just now settling in, ready to start broadcasting the London Olympic Games, where China expects to be a major power.

The building has two colossal, uneven leaning towers (the highest rises 768 feet) that are conjoined at the top by an enormous angular bridge. Conservative estimates put the cost at nearly $900 million; Koolhaas, for his part, says he has "no idea" of the price. What is certain is that the CCTV building now dominates the skyline of Beijing, just as it dominates the airwaves of the country.

It is clear that his background gives him a particular sense of affinity with the Chinese. He has a deep understanding of history, of war and pain, of complexity, of "ambiguity" (a favorite Koolhaas word), of order from chaos—and order in chaos—and always the ambitious vision for the future.

Koolhaas spent his kindergarten years playing amid rubble in postwar Amsterdam. His father was a busy journalist and fiction writer who turned out a new novel every year for 30 years. His grandfather was one of the city's most prominent architects. But when Koolhaas was a little boy the building that fascinated him most was the old municipal archive, which had been blown up by resistance fighters during the war. "We always played in the ruins," he recalls. "My mother always had to come and get us."

When Koolhaas was 8, his family moved to Indonesia, a place that gave him a lifelong taste for densely populated places and overlapping cultures. "I really thrived there, and my parents didn't," he says, "so it created a kind of premature emancipation, which really made me very decisive. I did the family shopping in the Chinese market. I had a fantastic time."

"It made me at an early age aware of very many different peoples, many different ways of living, many different ways of being happy—probably also many different ways of being religious. Because I had seen Christianity, Islam, Buddhism when I was 8, and actually experienced them. So all of that I think was very crucial. We went to Indonesian schools and had to live more or less an Indonesian kind of life." The return to Amsterdam when Koolhaas was 12 was not a happy one. "Suddenly, Holland was 'organized,'" he remembers, and that was "a shocking awareness." (Nonetheless, he still lives in Amsterdam and is perversely proud of the fact that the Rotterdam building housing his own headquarters is "completely nondescript.")

Koolhaas started out his adult life as a journalist and even tried his hand at screenplays, including one, unproduced, for the American soft-porn king Russ Meyer. But Koolhaas learned early on that buildings and cities had narratives too—"like scripts," he says—and that he might be able to shape urban environments through his words as well as through drawings. One of his academic theses while attending architecture school in Britain was on the Berlin Wall. His breakthrough to international acclaim came with the book Delirious New York, which grew out of his experience in the city in 1972. In those days "it was the pits," as he says, but it also had a tremendous reserve of excitement, adventure, humanity, and possibility.

Forty years later, Koolhaas talks about the extraordinary promise of China. "You realize that you work in a country that had one of the most impressive civilizations, longer than almost any other country. So that, in itself, gives a sense of awe and privilege. You also realize that it is a country with a recent history of enormous turmoil, but also enormous efforts to overcome those turmoils."

Koolhaas notes the "incredible determination and organizational competence" of the Chinese "and of course also the ability to orchestrate enormous projects that we here simply don't know how to do anymore." And he goes further when he talks of CCTV: "I would say it's a building that the Chinese could never have thought of but that we [in the West] could never have built."

During a teaching fellowship at Harvard in the mid-1990s, Koolhaas and his students traveled to the Pearl River Delta to look at the way the Chinese were building entire new cities. They took away a profound sense of the youth and energy driving many of these projects. So, when he got the call in 2002 to join the competition for the CCTV headquarters, "I knew more or less what to think about China," he recalls. The regime was not democratic, certainly. "But in the previous six years I had seen how it had been able to lift enormous amounts of people out of poverty and give them a lot better lives, and also in those lives introduce a lot of freedom of choice."

At that moment in 2002, Koolhaas himself had to make a pivotal decision. New York's World Trade Center, which he regarded as "incredibly beautiful" and "the one building that lifted New York on a different plane," had been destroyed by terrorists. America was traumatized, and many of the world's great architects were competing to design a new, palliative tower on the site of the wreckage. Koolhaas did not take part. He wasn't sure it was a job for someone who was not from the United States, but he was sure the shifting politics and parameters around the project would be extremely difficult. By comparison, Chinese authoritarianism has a kind of ruthless, and comparatively reliable, clarity. In any case, he decided to keep his focus on the CCTV project instead.

Koolhaas knew there would be political criticism. But the architect, whose clients, in addition to the Beijing politburo, include princes from the Arab Gulf States, has deflected questions about whether he prefers to work for authoritarian regimes: "You'll never get me to sign off on that," he joked when a German journalist asked him the question a few months ago. (As evidence grew of Syrian regime brutality, Koolhaas dropped out of an ambitious plan to build a museum in that country.)

In Beijing, the CCTV headquarters is the center of the most powerful propaganda arm of the Chinese state. And the building's enormity, in every sense, could be caricatured in Orwellian terms. CCTV could never be called a Freedom Tower—except with irony. For Koolhaas, though, there was one overriding consideration: "China is the biggest story of the first part of the 21st century," he said. "I really think that we all have a stake in the outcome, and therefore it is crucial to participate in it when you have an opportunity. I mean it's as simple as that."

The finalists competing for the CCTV contract were picked by the Chinese government with studied symmetry: five Chinese architectural firms and five foreign ones—two American, two European, and one Japanese. After Koolhaas won, he quickly enlisted one of the Chinese firms for his team and, in the early days of the project, about a dozen of its staff worked with Koolhaas in his Rotterdam offices. ("They started a Chinese restaurant downstairs," he says, "because they thought Dutch food was so horrible.") Then the work shifted back to Beijing, where it was overseen by a project director who answered to one of 21 vice presidents at CCTV, who answered to the president of the network, who answered to the highest powers in the land. Koolhaas estimates that over the last decade he visited the Chinese capital about once a month to coordinate with the Chinese, a little like an orchestra conductor, pulling together the massive structure. As it grew, so did Koolhaas's excitement.

Then, just as the project was nearing completion in 2009, a companion building meant to house a luxury hotel and a theater suddenly went up in flames: a towering inferno illuminating the night sky of Beijing and throwing ominous shadows on the walls of CCTV. That was "the most difficult moment," says Koolhaas with such understatement as to be almost inscrutable. Fireworks had hit the building during celebration of the Chinese New Year. It was a question of "exuberance, sheer exuberance," he says, "because it was an incredible moment, because that building was almost finished, CCTV was almost finished. So it was simply to celebrate—and it was a nightmare." Once again, working closely with the Chinese, "we were able to overcome that nightmare," he says.

After all this research, all this planning, all this money, all this labor, and this nightmare, what is left of the dream? The intellectual and aesthetic revolutionary in Koolhaas hopes that his building will have an impact on the way the Chinese see themselves and their world. "The Chinese have an enormous obsession with stability," Koolhaas said as we studied a model of the CCTV loop in the conference room he calls the Aquarium. "To introduce in China's main city, as one of the important buildings, a building that is not the same from any angle, and that kind of changes as you move—I think that in itself introduces an experience of what creativity means that has not existed there before." The building has what Koolhaas calls "totally unstable energy," and "that is for me a genuine achievement—and also new."

His favorite photographs of the CCTV building (many taken by his grown daughter, Charlie Koolhaas) show it looming on the horizon above the rooftops of working-class neighborhoods and of the Chinese Imperial Palace, known as the Forbidden City. "For me," says the architect, "the building has almost a mysterious ability to associate itself with almost anything around it, with both the poor and the rich."

Whether it reflects more the culture and history of China at this point, or of Rem Koolhaas, is hard to say.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.