Health and celebrities are an intoxicating mix. Major disease organizations chronically search for famous faces to represent them—and for good reason. Celebs make a difference.

Michael J. Fox, who was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 1991, has raised awareness—and large amounts of money. Since the Michael J. Fox Foundation was launched in 2000, it has funded almost $196 million in Parkinson's research. And Fox is open about the physical effects of his disease. He'll soon appear on CBS's series The Good Wife, where he'll play a lawyer "willing to use anything in court, including symptoms of his neurological condition, to create sympathy for his otherwise unsympathetic client: a giant pharmaceutical company," according to the network.

Autism is another one of Hollywood's chosen causes. The condition has inspired exceptional acting (Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man) and persistent debates (Jenny McCarthy's stance on vaccines). At its best, Hollywood tells stories that captivate, educate, and illuminate. And this month, Los Angeles magazine, attempts to do just that with a special package of pieces about autism, which you can read here for $3 if you can't find the magazine on a newsstand or in a bookstore near you.

The main feature, a tell-all piece by actress Angie Dickinson (as told to writer Ed Leibowitz), is powerful stuff. It teaches us about the joys of human variation and reveals the emotional turbulence that autism can stir up in families. Dickinson is candid, humorous, and pensive as she tells the story of her only child's struggle with Asperger's.

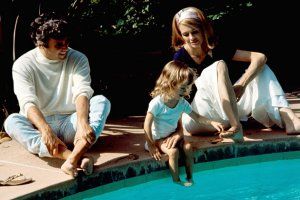

Nikki Bacharach, Dickinson's daughter with composer Burt Bacharach, was born three months premature in the summer of 1966. She weighed 1 pound, 10 ounces. The baby was immediately put into a preemie isolette and no one was allowed to touch her—a fate Dickinson believes was linked to her daughter's lifelong sense of isolation. "Even the doctors back then didn't know the value of touch, that if you never get touched or hear a loving voice or get held in those first months, you won't ever feel real or feel connected to anything. Not so long ago I was watching 2001: A Space Odyssey for the umpteenth time with Nikki, and it hit me: you know that scene where the astronaut gets cut off and just floats into space? That's how Nikki felt—how kids who have autism feel every minute of their lives. For the rest of us who can connect and ground ourselves so easily, it's impossible to comprehend."

Nikki didn't talk until she was three, but she did develop into an athletic kid who participated in gymnastics, horseback riding, ballet, scuba diving, and swimming. At four, "she could play piano like a prodigy," Dickinson writes, but she had disturbing behaviors—she cut the hair off her dolls and the tails of her toy horses. And she saved everything, including an old battery and dog poo, on top of a dresser in her closet.

After Nikki's birth, Dickinson stayed close to home. "I was continually keeping her connected, talking to her, hugging her, keeping her in a realm of comfort and familiarity, not letting her 'drift into space,' " she writes. But Nikki's behaviors—as she got older she tore pages out of books and kicked walls when she was frustrated—continued. Decades back, autism was not the medical phenomenon it is today. Few people even knew what it was, Dickinson writes:

"In the early 70s, you have to understand, we did know about mental retardation, and maybe a few doctors talked about autism, but how could Nikki possibly have either of those when she could express herself, draw, and play piano so brilliantly, when she had a great sense of humor, did well in school, and got along so beautifully with her friends? How could somebody say there was anything really wrong when we'd never met or even heard of anyone who was going through what she was going through?"

Nikki started seeing psychiatrists when she was about 8, but they offered little help. She was a tough kid with constant and demanding needs, all of which caused tension between Dickinson and Bacharach, who split up in 1976, after 11 years of marriage. "It's really, really hard and I don't blame anyone for leaving," she writes. When Nikki was a teenager, Dickinson says she gave in to Bacharach, who thought their daughter needed some distance, and sent Nikki to the Constance Bultman Wilson Center, an adolescent psychiatric treatment center in Minnesota, where she lived for 10 years. But Dickinson wasn't fond of the place:

"They were trying to make her into something she was not—somebody who could hold down a job. Somebody who could drive. They forced her to drive, which was insane. She totaled one car and wrecked another pretty good.They were trying to make her like everybody else. Her psychiatrist there told her, 'Nikki, someday your mother is going to die, and then you're going to have to be responsible for your own self'—which put her into a spiral she never got out of."

Dickinson first read about Asperger's right here in NEWSWEEK, she writes. But finding a diagnosis didn't make Nikki's life any easier.

"My sister sent the article to me and said, 'This sounds just like Nikki.' The article is from July 2000. I still have it. I circled the last paragraph, where it says that an institution is the last place these people should ever be sent, but it was too late for Nikki. I finally went to UCLA, and after examining her, the doctor there said she might have Asperger's. I said, 'Doctor, she does have Asperger's.' He didn't disagree. For Nikki, knowing what she had didn't help at all. She still simply couldn't cope."

In 2007, Nikki Bacharach committed suicide by suffocating herself using a plastic bag and helium. Dickinson doesn't go into the details of her daughter's death, but she says Nikki read Final Exit and talked a lot about suicide. She remembers watching her daughter sing in church on her last Christmas eve: "I could hardly hear her over everybody else, but when I looked at her, I smiled at how much gusto she had singing those Christmas songs. She was free and at peace at that point because she knew where she was going."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.