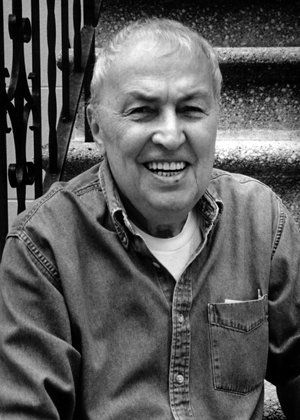

When experimental novelist David Markson was found dead in June, at the age of 82, the bookish dutifully took to mourning. Among postmodern American writers (some of whom have enjoyed cranking out the occasional several-hundred-page doorstop), Markson was one of the most pleasingly restrained and skillful. While sacrificing nothing in the complexity department, he had a gift for bringing us affecting characters, intellectual firepower, and bold narrative structures. And he could do it all in the space of, say, 190 pages (as in his last novel, titled, sure enough, The Last Novel). Thus, we saw a weighty, respectfully lengthy New York Times obit, more personal (and appropriately abstract) notices on blogs, as well as additional remembrances on literary sites such as N+1. People passed around the old David Foster Wallace Salon piece about "direly unappreciated novels," in which the author of Infinite Jest proclaimed that Markson's Wittgenstein's Mistress was "pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country."

The Internet had what it calls a "sadface," and then it moved on.

Mere weeks after that boomlet of attention dissipated, items from Markson's private, annotated library—each identified by the author's signature on the flyleaf—started showing up for sale at the Strand, a used-book store in New York that Markson himself had frequented. Somehow, no one had thought to box up his books and request bids from topflight academic archives, like the University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center. (While there's no doubt that Markson's library doesn't hold the same academic interest as Wallace's papers, you'd think some archive somewhere would have ponied up at least slightly more than the book buyers at a discount-inclined warehouse.) Instead, the volumes went into the nation's regular ol' mill of used books "with some markings"—as sellers would say on Amazon Marketplace.

And that would likely have been that, had not an anonymous Strand customer purchased one of the many copies of Don DeLillo's White Noise and then subsequently picked up on the witty, contrarian mind at work in the book's margins. Checking the inscription on the front page led the new reader to identify the book's prior owner: David Markson.

The next person to be notified of the find was Jeff Severs, an instructor at the University of British Columbia, who received the following by e-mail: "my [sic] copy of white noise apparently used to belong to david markson (who i had to look up) ... he wrote some notes in the margin: a check mark by some passages, 'no' by other, 'bulls--t' or 'ugh get to the point' by others. i wanted to call him up and tell him his notes are funny, but then i realized he DIED A MONTH AGO. bummer." Severs alerted London Review of Books writer Alex Abramovich, who wrote up the story and kicked off a mini–treasure hunt among a certain set of New Yorkers within running distance of the Strand.

The bookstore, which has given Markson's own novels pride of place on a display next to the main information desk, hasn't set aside books from his library in a special cart. Nor are they sitting in the store's "rare book" room. Markson's library has just been absorbed into the general merchandise. After poking around needle-in-a-haystack style for a few hours the other day, I managed to stumble across only a couple of titles: a half-century-old two-volume copy of Don Quixote ($25) and a book of literary criticism by Albert J. Guerard, titled The Triumph of the Novel ($12.50). In that latter case, I was so sure it was a Markson book that I had to peel back the Strand's for-sale sticker, which it turns out was covering up Markson's signature in the northeast corner of the book's first flyleaf page. (Had you been there, you might have thought I was performing some DaVinci Code–level sleuthing, based on the exclamation I uttered upon uncovering Markson's hidden name.)

Next I spoke with a bookseller who encouraged me to rifle through the philosophy section downstairs. "He had a lot of Heidegger, but most of that's gone," I was told. (Judging by the comments on the London Review of Books Web site, I believe I got to the gold rush approximately 12 hours too late to pick up Markson's copy of Pound's Cantos or the volume of Melville's early novels. And I was several days too late to snap up his trove of Gaddis and Roth.) Still, I did find something stunning in those philosophy stacks: a lightly marked copy of the Jean-Paul Sartre book Anti-Semite and Jew. Since anti-Semitism was one of the subjects of Markson's The Last Novel, I grabbed it with great anticipation. Again, the signature was partly covered by the sale sticker. But indeed it had belonged to Markson, who had placed checkmarks next to many of Sartre's turns of phrase—such as "If the Jew did not exist, the anti-Semite would invent him," and this one:

There is in the words "a beautiful Jewess" a very special sexual signification, one quite different from that contained in the words "beautiful Rumanian" [sic], "beautiful Greek," or "beautiful American," for example. This phrase carries an aura of rape and massacre. The "beautiful Jewess" is she whom the Cossacks under the czars dragged by her hair through the streets of her burning village.

Passages like this get at the underlying tragedy of Markson's scattered library. It's not just about his fans' emotional attachment to his legacy (though it's also about that). What's really at stake here is the chance to glean more information about his famously allusive late style. While he started out writing entertainingly pulpy crime and Western stories (one of which was turned into a movie starring Frank Sinatra), the final postmodern works for which he is best known were all built from a personal library of culled aphorisms, anecdotes from the lives of artists, and literary quotes. In The Last Novel, the unnamed narrator (called "Novelist" by Markson) quotes both Elie Wiesel and Hitler on the subject of Jewishness. Thus, Markson's reactions to Sartre's writing on anti-Semitism are frankly worth a hell of a lot more than the $10 I paid to acquire them.

After cosigning several of Sartre's insights on "the Jewish question" in the course of this book, though, there comes a point at which Markson is no longer willing to keep on nodding. On page 129, Sartre veers into broadly essentialist caricature about the "Jewish sensibility," writing: "It is, one suspects, deeply marked by the choice the Jew makes of himself and how he understands his situation." Below, Markson issues the priceless response: "Dear Jean-Paul—How can you be sometimes so smart and sometimes so stupid?"

When I read this, I laughed out loud. Then I almost threw up in disgust, given the book's too-easily-discarded status. But of course I bought the Sartre to take home, along with Markson's insights into Cervantes and his markings alongside the literary criticism of Faulkner, Dickens, and Dostoevsky. Still, when I walked out of the Strand I felt a good deal more like a criminal than I'm accustomed to feeling after I've purchased books. (Then again, as a friend told me later, the collection had already been dispersed, so individual agency was sort of moot.)

I'm sure I'll get a lot of additional excitement from following along with Markson the next time I tackle Quixote or Dostoevsky's Demons—though there's no good reason for me to be the only one who does. It seems others who've contributed to the privatization of Markson's library feel the same way, as a Facebook group has been created for us to speak up, declare our purchases, and upload scans of particularly interesting pages. It's a good start. But if and when an academic archive expresses a serious interest in acquiring all these books for future scholars, I'll pledge now—in Markson's memory—to send my three titles along for free (after I get a chance to read them first). I'll even pay for the postage.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.