One of our most venerable clichés describes artists as channeling the spirit of their age. But what about someone so finely tuned, he reflects an era that came after his own? That seems to be what happened with the great Italian artist Alighiero Boetti, now the subject of a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Boetti was born in Italy in 1940, in the industrial city of Turin; in the mid 1960s, his found-object sculptures briefly made him a major figure in arte povera, Italy's most famous postwar movement. By 1969, he had veered off to become his homeland's most important conceptual artist—and then, in 1994, when he was only 53, he died in Rome of a brain tumor. As a person, Boetti belongs to the past, but his works feel totally of the present moment. That may be why he's getting even more attention and bigger shows than he did in his lifetime.

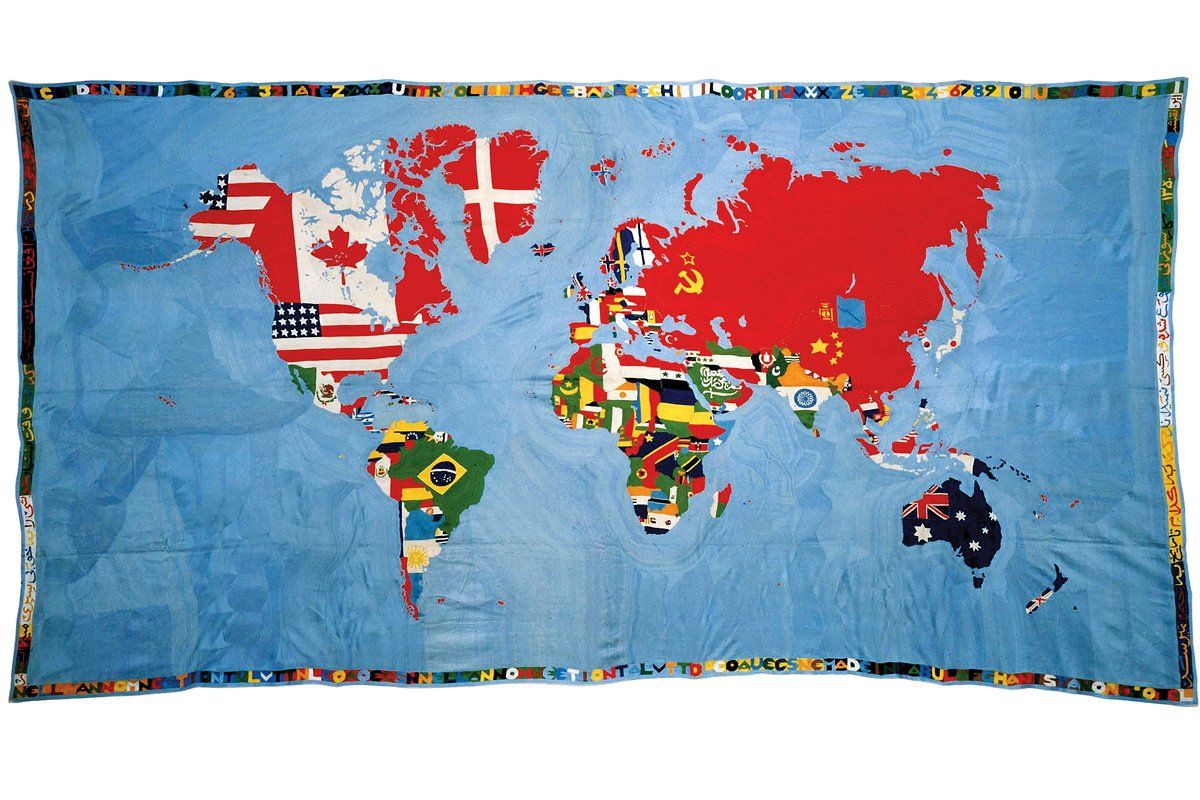

Boetti's best and most famous pieces, his "maps," could be all about the globalized world of the 21st century. He began the series in 1969, when he took a map of the world and filled in each country with the design of its flag. The landmass of the United States is striped red and white with a blue field of stars; the U.S.S.R., as it was then, is a vast stretch of red with a hammer and sickle. Over the next two decades, Boetti repeated this work more than 200 times, which lets us watch as frontiers change and old flags get replaced by new ones. The maps talk about the artifice of borders, and about the symbols that represent the nation-state to us. But there's more than abstract geopolitics involved with the project: in 1971, for no particular reason, Boetti ended up in Afghanistan, where he got local women to execute his maps as huge embroideries. When the artist first began visiting Afghanistan, the country was just another remote place where hippies liked to gather. By 1979, when the Russians invaded and Boetti's visits stopped, it was on its way to having the central role it does today—which Boetti managed to mark by continuing to work with Afghan exiles in Pakistan, and by letting them annotate his maps with comments on their fate. (He's also said to have had direct contact with the mujahedin, to the point of visiting with Ahmad Shah Massoud, who was killed by al Qaeda just before 9/11.) Boetti had no way of knowing that the attitudes of the Afghan people would go on to become central in world history—but somehow he didn't need to know it to make art about it.

Boetti's Afghan works don't only prefigure today's foreign affairs, they also predict where art would end up. Collaboration is one of the watchwords of art making today, especially when the artist cedes control to partners from outside the art world—as Boetti did to his Afghan craftspeople, who often added their own colors, thoughts, and decorations to Boetti's designs. (You could also say his works are about that 2012 hot-button topic, outsourcing.) Current artists prefer mechanical making or casual craftiness to the high finish of handmade fine art, and they blur the borders between art and design, form and function, play and work, the consumer product and the museum treasure—as Boetti also did. (One early piece was a chrome handrail, meant to be leaned on as you relaxed with his art.) Like Boetti, today's trickster artists conceal or confuse their roles as author, which in Boetti's case extended to pretending to be twins with the first names Alighiero and Boetti, working in partnership. And of course, a final hallmark of 21st-century art is to care less about looks than ideas and conceits—or, as Boetti said, "in effect there are five senses, and thought is the sixth" and "beauty is an expression of thought and of the urge to express it." Using thought as a medium has expanded the art of our era to include almost anything an artist does, from cooking curry for museum visitors (as in the case of the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija) to improving slums (as Theaster Gates has done in Chicago). Boetti made an early contribution to this practice of "relational aesthetics," as it's now known—an art based on human interactions rather than objects—when he opened his One Hotel in Kabul, which was just a cheap place for travelers to hole up. "Creativity also means opening a hotel," the artist once said. (To give an idea of how much Boetti and this project still matter, a central piece in this summer's great Documenta art festival in Germany presents a younger artist's attempts to find where that hotel stood.)

Looking at Boetti's total output, which moved from building-supply sculptures to esoteric games with words and dates and numbers (one piece lists the world's 1,000 longest rivers) you can trace some of the same tensions that are shaping the art scene today. During his early moment as an arte povera star, Boetti's elegant stacks of concrete beams and cake-platter doilies—which find close cousins in work being made now—started out seeming like radical rejections of standard art making. Very soon, however, they seemed to become just more fancy baubles, caught up in the usual hype of the art market and museum culture. That made Boetti leave them behind for work that was barely material (returned letters he'd deliberately misaddressed) or more frankly political (his maps, as well as tracings from news photos). Already by 1969, Boetti seemed to feel that the old art traditions had reached a dead end, and he spent the next 25 years trying to find a way out. Today's art makers and art lovers feel some of that same hopelessness; we look back at Boetti, to see if his escapes are still open to us.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.