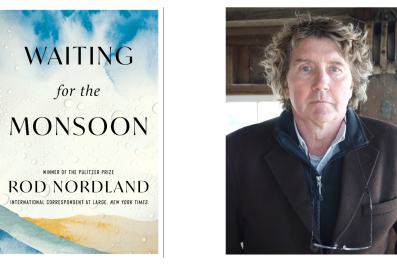

Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent Rod Nordland has covered global conflicts for almost five decades for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Newsweek and The New York Times. Reporting on wars and government upheavals in over 150 countries from Nicaragua to Cambodia, Bosnia and Afghanistan, he confronted death on a regular basis. Yet his diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme grade 4 in 2019 led him to confront another, much more personal battle. Glioblastoma, with about 12,000 newly diagnosed cases in the United States each year, is one of the most aggressive forms of brain tumors. It has a five-year survival rate of only about 6 percent, and it's what killed President Joe Biden's son Beau and Senator John McCain. In the midst of it all, Nordland did what he does best—write. Below is an excerpt from his book, Waiting for the Monsoon—a personal story of fighting cancer and of his experiences as a reporter seen through the lens of his own mortality.

One of the dangers of being a foreign correspondent, or perhaps just an unintended consequence, is becoming an old bore, mired in past wars and spewing vivid but dated anecdotes. I don't want to be that person, and this book is about the very different combat zone in which I now find myself—it's not just about the previous ones. But as I look back, as I ponder mortality and the certainty that I now have more yesterdays than tomorrows, I can't help but reflect on some of my extraordinary near misses when I was young, physically strong and confident of my invulnerability.

One of those events took place when I was in Thailand for the Philadelphia Inquirer. One night, a small group of colleagues and I sat playing gin rummy as we waited to be executed the next morning. We had torn pages from our notebooks and made a crude deck of cards, but the soldiers who were guarding us indignantly confiscated them, pronouncing card games illegal.

"Oh, but extrajudicial killings are OK, is that it?" I asked, in my bad but serviceable Thai.

"Hubpak," one of the soldiers said—which, in rough translation, means "Shut the f*** up."

This was in 1980, when the army from Vietnam had invaded Cambodia and was destroying the Hun Sen and Khmer Rouge regime. The enormous Khao-i-Dang refugee camp had been hastily created in Thailand for Cambodians fleeing after the fall of the Khmer Rouge. Hundreds of thousands gathered there. A group of Thai soldiers had taken me and a few fellow journalists captive because they were deeply angered that we had seen them on the Cambodian side of the Thai border—where they were forbidden to go. I had found that Thai soldiers were also directing the Cambodian guerrilla forces that were fighting the Vietnamese—they did not appreciate my knowing this fact, much less reporting it. They arrested us and declared they would execute us in the morning.

When faced with an unpleasant but unavoidable circumstance, I am blessed with a helpful reflex: I fall asleep. For instance, I'm absolutely terrified of landing on aircraft carriers. During the First Gulf War, we journalists often stayed for weeks at a time on an aircraft carrier. Landing a transport plane on one generally requires deploying a tail hook that must catch a 3-inch-thick steel cable lifted across the deck runway during the approach, at over 100 miles an hour. When the plane hits the deck, it is hooked to a dead stop in a couple of seconds. The only way I could face that sudden landing was to flip my sleep switch and go dead asleep until we had slammed to the deck and were stopped. Upon opening my eyes, I was shocked awake and delighted to be alive. This delight in being alive has become more frequent these days. A terminal illness will do that for you.

On the eve of our promised execution, my friends were incredulous, not to mention mildly outraged, when I zoned out. "Your last night alive, and you're going to spend it sleeping?" one fellow journalist asked.

"Yes," I replied, "and get a good rest so that first thing in the morning I can jump that fence and run like hell into the jungle."

The soldiers had no idea what we were talking about, but they didn't like the sound of it. "Hubpak," they repeated.

When I woke up, I saw a Red Cross delegation. Once they took our names, we knew that we would be safe. When news of our imprisonment leaked out, an international furor ensued.

I learned an important lesson during those border skirmishes. I was internally still the 18-year-old tough guy from Philly, and like so many young men, I had not realized that I might be mortal. That attitude ended the day I foolishly went up to the front line during one of those pointless factional skirmishes. That time, a fighter was head-shot, and his distraught comrades forced me at gunpoint to take him to the hospital in my Avis rental car. That victim and I had been standing shoulder to shoulder, listening to bullets whiz over our heads. The bullet that hit him could just as easily have killed me.

My Last War

To have been a foreign correspondent who covered Afghanistan on and off for nearly 40 years, including the past nine years straight, then to be sidelined by a brain tumor during the painfully historic moment when the Taliban came back to power in August 2021, during a disastrous exit by the United States, was to feel an incomparable level of frustration and despair.

I knew this story. I had the contacts. I had been in regular touch with Zabihullah Mujahid, the Taliban spokesman and the head of their media department. In the past, with the help of our interpreters, we would play out all the potential scenarios. I knew that when a government was as corrupt as the one supported by the United States, it was inevitable that the Taliban would eventually triumph and return.

Which is just what happened. I had even asked the Taliban spokesman through an interpreter whether it would be safe for me to remain in Kabul, and he assured me it would be. Whatever else the Taliban spokesman was, I believed, and had ample evidence to support the belief, that he was a man of his word. Once, years earlier, the American official in charge of what they called strategic communications asked me what the Taliban were doing better than the Americans in interacting with the American media. I earned his probably undying enmity by suggesting that he invite Mujahid to a handling-the-media seminar with the American military, which I said I would be happy to arrange—a proposal that was only slightly tongue-in-cheek.

"Seriously," he said, "what do they do that we don't?"

"Well, for starters, their default position is to tell the truth. If you ask them about something and they can't answer honestly, they say so; if they promise to investigate and get back to us, they do, in hours, not after months of fruitless investigation. And they are always far quicker than you guys at responding to us."

"That's because they don't have to worry about getting the truth, and we do," the admiral said.

"You do?" I said. "I'd say on that score you're about tied." I immediately recalled the time I was working on a story about the problematic U.S. efforts to rebuild the Afghan military. There was an interview I had with the Afghan general in charge of the helicopter wing, which was in the process of getting scores of new helicopters designed by the Americans for the Afghan Air Force. As a horrified American public affairs officer, a colonel, listened aghast and tried in vain to get the Afghan general to shut up, the general proceeded to ridicule the new helicopter, saying it was unable to reach an altitude high enough to clear the mountains ringing Kabul, where they were to be based. It was also poorly armed and inadequately armored. They could not even stay aloft in much of the country, due to the thinner air at high elevations.

But instead of being there, in the midst of the chaos and yet another transformation of that country, I was in New York, reading everything that I could. As I watched the chaotic scenes at the Kabul airport, I thought of how many times I had flown in and out of it, I thought of the stories I did, the people I knew and my conviction that what was unfolding now before me had been inevitable, as many of my stories here have demonstrated. Not to be a part of it now seemed inconceivable.

And yet I had moved into a different theater of war, one with negligible international implications but cataclysmic personal ones.

I learned over the years that if there was a single golden rule for reporting from a conflict zone, it was this: you need an exit plan because you must live to tell the story. One always needs some strategy for removing oneself as quickly and safely as possible, should things get out of control—which they so often do. If it gets too dangerous, how is one to get out? This golden rule, it turns out, is true both geopolitically and personally. As I watched the mess at the Kabul airport, I could see that the United States clearly did not have anything resembling a coherent exit plan—much less any indication that they had weighed the risks in a thoughtful way. In the war in which I find myself now, a battle for my life, the exit plan is more difficult to configure. What does it look like to escape from GBM-4?

In every story we do in a war zone, there's a calculation at the base of it, the risk versus the reward. I'm accustomed to calculating survival odds. Just making it alive to the publication of this book will beat the odds of 6 or 7 percent. From diagnosis to death at my age, the median life expectancy for GBM was 15 months, meaning the bottom date on my tombstone should have been roughly November 5, 2020—age 71. I am writing this in 2023—which means, as my old war correspondent buddy George de Lama put it, I am now, and have been for almost two years, "playing with the house's money."

Sometimes my exit plan becomes a thought experiment. I wonder if I can just buy some more time, "play for the come," as we say in poker, where I can keep the worst of the catastrophe at bay, muddling through with my therapy sessions and my rather limited life, until a brand-new, miraculous treatment for GBM is discovered. A treatment that will completely eradicate errant cancer cells and maybe energize the brain's plasticity so as to repair whatever region had been violated. As I daydream about this exit plan, I imagine seeing these few years of frailty and illness as an intermezzo in my rich and engaged life.

But I am a realist, aware that this may well not happen. No matter how many billions have been spent on the cancer moonshot in Beau Biden's memory, who knows how much will be allocated for GBM, and even then, the length of time it takes from promising treatment to the market is, quite literally for many of us, a lifetime.

Excerpted from the book WAITING FOR THE MONSOON by Rod Nordland. Copyright © 2024 by Rod Nordland. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Correction: 03/07/2024 1:07 p.m. ET: Photo credits have been corrected