As cancer researchers expand the frontiers of their understanding of the basic science of cancer, biotech companies are using what they've already learned to mobilize the human immune system against cancer.

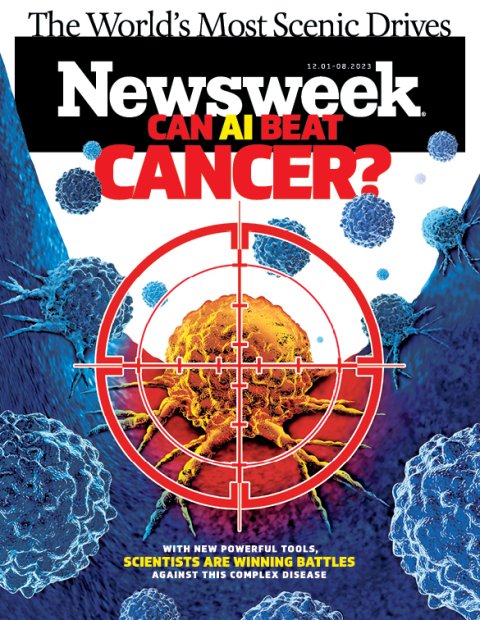

One of the most exciting developments are cancer vaccines. Scientists are using artificial intelligence to identify mutations in cancerous tumors that the immune system can recognize, then creating personalized vaccines designed to prime a patient's immune system to hunt them down and destroy them.

In 2017, Moderna, in partnership with pharmaceutical giant Merck, announced plans to start human trials with a personalized vaccine that targets solid tumors. To make a specific vaccine for each patient, they start by sequencing the DNA of the patient's healthy cells and cancerous ones. By comparing the two, they identify hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of mutations in the cancer cells. Then they use AI to choose 34 mutations in each patient most likely to elicit a strong response from the immune system. To train the algorithms, the companies have partnered with university medical centers to gain access to biopsy samples.

AI also takes in basic immunology principles about which of the characteristics of proteins and amino acids are most easily detected by the body's immune cells.

Based on this information, the company then creates a personalized RNA vaccine which, when injected into a patient, triggers a major response, causing the body to churn out an army of immune cells specifically designed to seek out and attack cells expressing any of the 34 proteins. RNA vaccines, which were used to develop the COVID-19 vaccine, introduce instructions into cells that cause them to produce a specific protein associated with a virus or a tumor (but not the virus or tumor itself). The vaccine causes the body to produce enough of the protein that the immune system is likely to detect it, identify it as foreign and begin produce immune cells designed to seek it out and destroy it.

The company's approach is based on a "deep belief that the immune system can defeat cancer," Stéphane Bancel, Moderna's CEO, tells Newsweek. That belief stems from a simple fact: In healthy individuals, the immune system routinely kills cancer cells before they become tumors. That is why, he says, it makes more sense to design treatments based on the genetic signature of the cancer being targeted than the traditional approach of targeting cancer based on which part of the body it is found in.

"What we know today that we didn't know 20 years ago is that cancer is always a disease of the DNA—it's caused by mutations," he says. "People used to think about cancer as a disease described by which organ it was presenting in. But a description of the organ where you have a mass doesn't tell you anything about the mechanism that has driven this cancer and what genes are driving this cancer and the spread and the growth of this cancer."

In June, Moderna and Merck reported that roughly 68 percent of patients with stage 3 and 4 melanomas responded positively to the vaccines; 32 percent either saw their cancer continue to spread after treatment or died. The prognosis will also improve, he says, as scientists learn more.

"We don't know yet why the vaccine works on some people and not some others," he says. "There is so much we still don't know about the immune system. But I'm quite optimistic. almost every week there's a new paper or new insight that is helping the field."

Genentech, a San Francisco–based biotech company, is also developing a vaccine designed to attack individual tumors. It has partnered with BioNTech, which like Moderna also gained global recognition for its role in creating mRNa vaccines during the pandemic.

In May, Ira Mellman, Genentech's vice president of cancer immunology, and his collaborators published a study in the journal Nature detailing the effect of their vaccine on 16 people with one of the most common, and deadliest, types of pancreatic cancer, which has a five-year survival rate of about 12 per-cent. The vaccines activated T cells capable of recognizing the pancreatic cancer in half the patients. A year and a half after treatment, all those patients remained cancer free; one patient's T cells, produced by the vaccine, appear to have eliminated tumor cells that had spread to the liver. By contrast, for those eight patients whose immune systems did not respond to the vaccine, their cancer returned within just over a year on average. Last month, a phase II clinical trial began enrolling the first of 260 patients at nearly 80 sites around the world. Those numbers are expected to continue to improve in the years ahead.