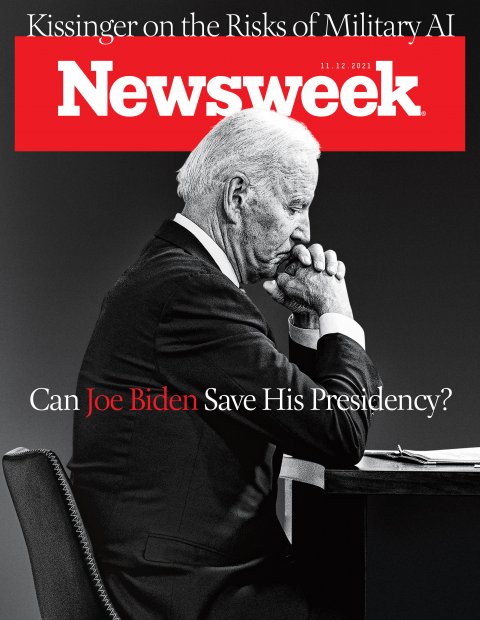

Joe Biden's presidency was meant to be defined by calm, experienced competence. Yet just nine months into his term, he has been teetering on the brink of failure. Vicious infighting within his own party has threatened to torpedo his ambitious domestic agenda, encapsulated in two sprawling pieces of legislation that Democrats have not yet been able to vote out of Congress. Even before the bickering over the bills, Biden's claim to competence, based on more than 40 years in Washington, had been shredded by a calamitous exit from Afghanistan and an ongoing crisis at the southern border. Meanwhile, the off-year election results suggest Democrats will take a beating in the midterms, the COVID-19 pandemic grinds on, inflation is on the rise and there's sideline carping every day from the president's predecessor, Donald Trump, who seems to be campaigning three years early for a 2024 return to the White House.

Even as Biden announced the terms last week of a $1.75 trillion framework to salvage his signature "Build Back Better" legislation—cut in half from the bill's original $3.5 trillion price tag—his approval rating was taking a beating. The latest Real Clear Politics average has just 42 percent of Americans approving of the job Biden has done so far, while 52 percent disapprove; that represents a sharp downturn over the past two months and a nearly 14-point drop overall from his post-inauguration peak of close to 56 percent. No president in the modern era, not Jimmy Carter, not even Donald Trump, has fallen out of grace so swiftly this soon into a presidency.

With the midterm elections now just a year away, and Democrats holding the slimmest of majorities in Congress, Biden's nosedive has alarmed his political allies. And the off-year election results have only added to the worries. Republican Glenn Youngkin's victory over Democrat Terry McAuliffe in the governor's race in bellwether Virginia, where Biden won by 10 points last year, is a particularly ominous sign. In New Jersey, where Biden also won by double digits in 2020, the close governor's race in New Jersey between Republican businessman Jack Ciattarelli and Democratic incumbent Phil Murphy, who was leading by a substantial margin in late polls, is another signal of political danger ahead.

As political commentator Van Jones, a former adviser to President Barack Obama, said on CNN, "Democrats are looking over the edge of a cliff."

What's over that edge? Midterm elections are historically difficult for first term presidencies. Democrats lost 63 seats in 2010, two years into Barack Obama's first term, the worst performance by a sitting President's party since 1938. Obama memorably described the result as "a shellacking." Nervous Democrats now worry that 2022 could be worse.

The change in fortune has been swift. Earlier this year, when more and more Americans were getting vaccinated, Democrats were optimistic that the COVID-19 nightmare was behind us. Biden famously pegged July 4 as the demarcation point, the festive day when Americans could return to normal life. Biden's advisers believed the President could claim a big political victory on the issue that, more than any other, got him elected—and that would put the political wind at his back.

Then the Delta variant spread, the number of COVID-19 cases—and deaths—began to rise again. And Biden's approval rating began its precipitous decline.

Now there's a giant question mark hovering over his domestic agenda, with no clear signals yet whether progressives and centrists within the Democratic party will overcome their deep divide to vote through the slimmed-down social safety net bill, along with a separate $1 trillion infrastructure measure. Left out of the framework are several proposals that are top priorities for the liberal wing of the party, including paid family leave, dental and vision care for Medicare recipients and free community college. The legislation's price tag, meanwhile, is still higher than sought by moderates, who failed to immediately throw their support behind the revised Biden plan. On November 1, West Virginia moderate Joe Manchin publicly criticized the $1.75 billion price tag, saying, in effect, that it was fraudulent, the result of "shell games" and "gimmicks."

Before leaving for twin summits in Europe last week, Biden had struck an optimistic note, saying a reasonable compromise had been reached. "No one got everything they wanted, including me," Biden said in announcing the new framework at the White House on October 28. "But that's what compromise is. That's consensus. And that's what I ran on."

If the bill fails to pass Congress, it is not clear what Biden's fallback would be. Political analysts and Democratic insiders doubt that Biden could pivot to working with a new Republican majority in Congress and pursue "small ball" legislation of the sort Bill Clinton did when the GOP took the House in 1994.

The Republicans have a 47-member hit list of House Democrats they believe to be vulnerable, mostly moderates in districts Trump either won or lost narrowly. Among the higher profile names on the list are Tim Ryan, the veteran Congressman from Ohio, and Henry Cuellar from the Texas town of Laredo. Progressive Democrats, led by New York's Alexandria Ocasio- Cortes and Washington's Pramila Jayapal, chair of the Progressive Caucus, are much more likely to survive, and have little desire to cooperate with a GOP majority.

In short, if Biden fails to get his signature legislation passed, Democrats are staring at the possibility of a failed presidency, just one year into it—a concern Biden himself seems to share. Speaking to a group of House Democrats on Capitol Hill the morning he announced the framework, he said, according to a report in The New York Times, "I don't think it's hyperbole to say that the House and Senate majorities and my presidency will be determined by what happens."

The last modern presidency viewed as an abject failure was Jimmy Carter's over the four years from 1977 to 1981. But in the 1978 midterms, Democrats lost only three Senate seats and 15 House seats, retaining firm control of both chambers. Carter's presidency wasn't widely viewed as a "failure" until the attempted rescue of the American hostages in Iran ended with the crash of Desert One outside of Tehran in 1980.

A rout next year in the midterms would heighten concerns that Biden, soon to be 79 years old, was effectively a lame duck, and would intensify concerns (already bubbling beneath the surface among Democrats) as to whether he would even run again in 2024. Republicans, should they win both the House (where Democrats currently have a five-seat margin) and the Senate (which Dems control by just one vote), would control any legislative agenda, and there is already talk of impeachment payback for the Trump years. The GOP could conceivably seek to impeach Biden over the lethal Afghanistan debacle or his alleged failure to enforce immigration laws at the southern border.

That is why the Democrats' main concern now is straightforward: What can Biden do to avoid a failed presidency? Interviews with administration and Congressional sources, Democratic operatives and presidential scholars suggest the president still has time to salvage his first term. But he needs to act decisively—and quickly—to do so, particularly on the twin economic bills now being negotiated.

And indeed, White House and Congressional sources say, the President has been doing just that this entire autumn, actively engaging with the key Congressional players and negotiating a compromise in order to salvage his twin economic plans. After that, there are two other significant steps he could take to resuscitate his presidency. But the priority now, as veteran political analyst Larry Sabato of the University of Virginia puts it, the president "needs to channel his inner LBJ."

Being LBJ

What would that involve, exactly? Before he became John F. Kennedy's vice president, Lyndon Johnson was known as the "Master of the Senate." Whether through flattery or intimidation, he knew how to get what he wanted. He famously cut deals as Senate majority leader with Georgia Senator Richard Russell of Georgia and other southern Democrats to get the Civil Rights Act of 1957 passed—the first civil rights legislation passed since Reconstruction. That was a precursor to the historic civil rights bill LBJ got passed as president in 1964.

Throughout his campaign, Joe Biden repeatedly stressed that he knew how to reach across the political aisle and get things done. He would work with Democrats and Republicans, many of whom he had befriended throughout a long career in the Senate, and as vice president. In these deeply polarized times, Biden alone could turn down the political temperature and put the country on a path to "normalcy." It was a winning message, and his desire to be a unifier was the centerpiece of his inaugural address.

Now, Biden's first LBJ moment has arrived, albeit this time with a twist: Like Johnson before him on civil rights, he needs to unify his own party. The schisms are wide between the so-called progressive wing of the party, embodied by AOC and Senate Budget Committee chairman Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and the more moderate faction, led by West Virginia's Manchin, who has concerns about excessive spending, and Arizona Senator Krysten Sinema, who has pushed back against significantly raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy.

The two factions have been acrimoniously and very publicly spatting for months over their differences regarding Biden's signature safety net legislation, which originally encompassed everything from climate change and an expansion of Medicare, to the now-cut provisions for paid family leave and free community college. If passed in its initial form, the bill would have resulted in the most massive increase in the size of government in U.S. history—greater even than either FDR's New Deal or Johnson's Great Society.

Biden, White House and Congressional sources say, understood what needed to happen, and has been acting on it. Frustrated White House officials don't believe the President has been getting enough credit for assiduously trying to bang out a compromise between the two wings of his own party.

"You have to understand, the stuff Biden said during the campaign about compromise is who he is, and that goes for working with Republicans, or with members of his own party with differing views. This is the process," says a member of the White House's Congressional liaison team not authorized to speak on the record. Whether the bills now under consideration ultimately pass or not, White House officials say, this is how Biden operates—and will for the rest of his presidency. "He knows what he wants, but he also knows that compromise, as he has said over and over, is not a dirty word. The guy was in the Senate for more than thirty years, for God's sake."

As far back as the late summer, Biden knew he was going to have to work to bring the progressives and the moderates of his party together. In mid September he quietly met with both Manchin and Sinema at the White House to understand their concerns. And he stayed in touch with both of them constantly as Democrats scrambled to put together a framework for the Build Back Better plan before Biden left for summits in Europe.

He has also, aides and Congressional sources say, been equally active with the progressives, particularly Sanders and Jayapal. He met privately with Sanders at the White House on October 27, hoping to get the Vermont senator to back the framework he would announce the following morning. Just over a week earlier, the progressives had accepted that the original $3.5 trillion figure wasn't going to fly. Biden then acknowledged that publicly. A package closer to $1.7 to $2 trillion–far closer to Manchin's position than Sanders'—was more like it.

Throughout October, Biden and his aides continued to work with key members of Congress on what could stay in the bill and what could be jettisoned, as well as figuring out ways to raise revenue to defray the cost. Since mid-October, he has been actively engaged with all the key participants in the Hill to sort out which programs would remain in the final version of the bill, and at what cost. He has also been immersed in discussions, with Sinema, among others, to figure out how to pay for the new spending.

"The cat herding process has begun," says Sabato. "He appears to be doing whatever he has to do within his own party to cajole, entice, convince—do whatever he has to do within his own party to reach a compromise."

Progressives, the White House acknowledges, have made some tough choices. In meetings in mid- October, Jayapal and Sanders agreed to forgo the free community college component of the bill, so long as free, universal pre-K spending remained in the bill. (It has). Biden himself agreed to scale back an ambitious paid family leave proposal, something he had campaigned on, to reduce the cost of the bill and appease Manchin. That has infuriated some Democrats, but Biden as of late October was sticking to it.

Cutting deals on climate change programs has also been critical to keeping Manchin on board. Biden, White House officials say, specifically persuaded progressives to stand down on their pursuit of a plan that would have paid electric utilities to switch from coal fired plants to clean energy and penalized those that refused to do so. That, Congressional and White House officials say, helped keep Manchin on board. And Biden committed to spending up to $500 billion on climate action even without the clean utilities component.

This, Biden's allies insist, is precisely what Biden ran on: being able to lead people of disparate views and get things done. "Voters are looking for a return on what they were promised," says Jeff Horwitt, a Democratic pollster.

If Biden, in concert with Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leaders in the House and Senate respectively, can finish the deal (and as Newsweek went to press, that was still a big "if"), that would immediately set Biden up for another victory: passage of the roughly $1 trillion infrastructure bill, which would be the largest spending plan ever to modernize the nation's highways, bridges, airports and extend internet access in rural areas significantly. That bill–already passed by the Senate– is not nearly as contentious as the Build Back Better plan and even attracts some support from Republicans.

That, most Democrats contend, would change the political landscape significantly. They point out, accurately, that the individual aspects of the Build Back Better plan all poll well. "The legislation is popular with a clear majority of Americans," says Horwitt. The expansion of Medicare is supported by 54 percent of Americans, according to a recent Pew Research poll; the child tax credit by 55 percent and action on climate change by 53 percent.

The media coverage of the bill, which focused on the intra-party wrangling, has already begun to change. "Once you pass the bill, it delivers a lot of goodies to core Democratic constituencies," says longtime Democratic campaign operative Joe Trippi. It will give Democrats something substantive to run on in next year's midterm elections, which for the moment are setting up to be a disaster for the party. "It will, at minimum, help limit the damage," says Sabato.

The twin legislative victories, should they come, would also put a serious dent in the Biden-is-a-senile-incompetent narrative, so popular on Fox News and other right wing media. That is another reason why some White House and Congressional sources both emphasize that the sense of panic that washed over Democrats is overwrought. There is still a year to go before the midterms. Get the legislation done, start doling out the benefits and a lot of people will calm down. That, after all, is what LBJ did (albeit with far larger majorities in both the House and the Senate)to get his Great Society legislation passed. Joe Biden's ability to do the same—which many doubted—may rescue a presidency that had been at the brink.

The Biden White House has also begun to focus more intently on inflation, which polling indicates has become a central concern for voters—with a majority holding the president responsible for rising prices. Biden's allies note that while there is a limited amount of things that the federal government can do to effect rising prices, there are some things: ending the Trump era tariffs on everything from steel to aluminum to lumber is one of them. Those tariffs have helped elevate prices in industries such as housing. At the G-20 summit in Rome, Biden followed through. He told European leaders that their goods would no longer be subject to the tariffs Donald Trump had implemented.

Biden's union supporters may not like it—that's one of the reasons the tariffs remain in place—but he may have to explain to them why this needs to be done. He may also tap the strategic petroleum reserve to blunt the impact of rising oil prices. Aides say these moves would reinforce Biden's image as a pragmatist, not an ideologue, and may go some way to rebuilding his appeal with independent voters, which has collapsed in the last two months.

What else might Biden do to rebuild support?

Hold Someone Accountable—for Something

Many Democrats ruefully concede that beyond the wrangling over the Build Back Better legislation, the last few months have been brutal for Biden and his administration. And that the wounds are self inflicted. They point to the calamitous—and deadly—withdrawal from Afghanistan and the ongoing chaos at the southern border as issues that have damaged the Biden Presidency—in ways that are both obvious and subtle. The Afghan withdrawal was a plainly a debacle. The administration and its allies simply hope that it will recede in the memory of voters as time passes (though Republicans are already at work on attack ads they intend to bludgeon Democrats with in the midterms).

The more subtle problem is this: The Biden administration, led by the president himself, tried to spin the withdrawal as "an extraordinary success," touting the total numbers of Afghan citizens flown out of the country. What's wrong with that? Simply put, "he sounded like Trump," says a Democratic Congressman who did not want to be quoted by name in order to speak candidly. "It was like Trump trying to argue that he handled everything about COVID magnificently. It was exactly the kind of bullshit people voted against."

Biden ran as the grown-up, several Democrats said, and grown-ups—and the organizations they run—admit when they make a mistake and they hold someone accountable. Neither happened in the immediate aftermath of Afghanistan. "Someone—[Secretary of State] Blinken, [Chairman of the Joint Chiefs] Milley—should have fallen on his sword," says one Congressional Democrat.

The announcement that the State Department's Inspector General is going to launch an investigation into the Afghanistan withdrawal gives some hope that conceivably there could be some accountability. But most Democrats interviewed for this story are skeptical. "They just want to move beyond Afghanistan," says a Democratic staffer on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

That brings some to think of the ongoing border crisis. Over 1.7 million undocumented workers were apprehended at the border this year, the highest total in U.S. history and an many thousands more were "getaways"—migrants who got into the country. It is true that there is an "open borders" constituency within the Democratic Party that wants to increase immigration, legal or otherwise. But as any number of recent polls have indicated, that constituency is by no means a majority, yet the Biden administration seems to be acting as if it were.

Indeed, pollsters say among the most alarming trends in recent polling data has been a marked decline in support for Biden among Hispanic voters—a core Democratic constituency. Three polls in early October, for example, showed Biden's support among Hispanics falling to 43 per cent, down from 60 percent in May.

A big part of the reason? A majority of Hispanics, like a majority of Democrats overall, oppose mass illegal immigration. "Only the open border crowd approves of perceived chaos like this," says Ryan Pougiales, deputy director of politics at Third Way, a centrist Democratic think tank. "They [the administration] need to get a grip on this."

One way of doing that is to hold someone accountable for the ongoing chaos. That points in the direction of Department of Homeland Security Chief Alejandro Mayorkas, who for months mulishly declined to use the word "crisis" when discussing conditions at the border. He also flatly stated that "the border is closed" at a time when thousands of illegal migrants were pouring into Texas—something Americans could watch with their own eyes on television.

Later thousands of Haitians who had been residing in South America sat in squalid conditions for weeks under a bridge in Del Rio, Texas, and the Department of Homeland Security's initial, bizarre response was to try to shut down drones taking footage of that for Fox News. (It quickly relented.) Again, say administration critics, the point is to admit when something isn't going well and to be accountable for the mistakes by having someone take responsibility.

Many Democrats interviewed for this story agree with the overarching point—real leaders enforce accountability. But few actually expect any heads to roll over immigration. For the record, a White House spokesperson says the president "has full confidence in Secretary Mayorkas."

Take the Political Poison out of COVID

Nearly all Democrats concede that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has a lot to do with Biden's sinking poll numbers. Biden's entire candidacy was built around his assertion that he would "shut down the virus, not the economy." He told a CNN town hall during the 2020 campaign that Donald Trump was responsible for every COVID-19 death in the U.S. while he was president. Now, more people have died of COVID-19 so far in 2021—on Biden's watch—than in all of 2020 under Trump. Biden's inability to vanquish the virus—leaving aside whether that was ever a realistic possibility once the Delta variant emerged—is, for now, hurting him badly.

But maybe only for now. The number of COVID-19 cases nationwide is again on the decline, with daily cases down 57 percent since peaking at the beginning of September. There is a quiet but growing sense of optimism within the administration that the coming winter will not be as bad as feared. Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb has said that the pandemic is about to become "endemic." (An endemic virus is one that remains in the population but its impact is manageable, like the seasonal flu, for example.)

The improving numbers, some Democratic strategists say, gives the administration an opportunity to change the tone of the virus discussion and take steps to ensure the number of cases continues to shrink. But they are steps the White House isn't emphasizing enough, many health experts agree.

First, on tone: Biden has at times taken to scolding those who remain, for whatever reason, unvaccinated. In a September speech he said "our patience is running out," and "your refusal has cost all of us." The country, he has said, faced a "pandemic of the unvaccinated." And while his frustration may be understandable, it caused some squirming in the West Wing because the message comes across as divisive and thus "off brand," as one adviser puts it.

"It was hardly unifying," says a senior staffer to a Democratic senator from a red state, who, the staffer says, "was mortified" by the Biden September 9 speech. "It just was not presidential. Too often he sounds like the President of Twitter, not the President of the United States," adding, "Isn't that what we ran against?"

White House officials say the president's frustration mirrors that of the American populace more broadly when it comes to the unvaccinated—and they have, a senior official says, internal polling data that reflects that sentiment. But tone matters, and some Democrats worry that hectoring and shaming people might not be the best tactic. The administration is enforcing federal vaccine mandates and big private sector companies are following suit. The accompanying, polarizing rhetoric around the vaccine is unnecessary, these critics say.

Instead, persuade, cajole or entice people to get the vaccine. Persistently but civilly make the case that the numbers do not lie: People who get the shots are at far less risk of serious illness than those who do not. Part of the reason that message isn't breaking through is the virus, like so much else in American life, has become intensely politicized.

Tone aside, what are the substantive steps the administration could take to accelerate the virus's decline? Two administrations have successively fixated on vaccine development and, now, getting shots into arms, for understandable reasons. That focus, however, has left the United States seriously lagging in the use of another effective tool to combat the virus: the production and use of rapid testing devices.

The problem has been the Food and Drug Administration's cumbersome medical device authorization process. It doesn't treat rapid tests as public health tools but rather as medical diagnostic devices, which take significantly longer to get approved. As Harvard University microbiologist Michael Mina has argued, Biden could sign an executive order making rapid tests official public health tools.

Their widespread daily use would enable those who test positive to isolate themselves from school or the workplace. That would provide added comfort to those who have tested negative that the person at the next desk is virus free. This could also take some of the ire out of mask mandates, while helping reduce the spread. Mina, in an op-ed in The New York Times last month, noted that under Donald Trump's Operation Warp Speed, the public and private sectors worked together with great urgency to develop vaccines. They should do so now to provide the mass distribution of free daily testing kits.

Modifying his COVID-19 strategy, along with continuing to flex LBJ-like muscles and holding members of the administration accountable for missteps, might not collectively be enough for Biden and fellow Democrats to salvage the midterms next year. But they could do the next best thing: Limit the damage.

And perhaps more importantly for Biden, these steps would show him to be an active, capable and grown-up president headed toward 2024. And that, even at 81—the age he'll turn in November 2023—might make him viable for another term.