The COVID-19 pandemic may have made a future pandemic more likely. In a terrible irony, nations eager to get a handle on the virus and its variants are building high-containment laboratories at a brisk pace, ensuring that more scientists continue to experiment on dangerous pathogens even after the current threat fades—increasing the likelihood of future lab accidents that could release dangerous pathogens. Regardless of whether the current pandemic got its start in a laboratory in Wuhan or in animals—a mystery that may never be resolved—the mere fact that it's possible is reason enough to take precautions against any future occurrence, biosecurity experts say.

"Without a doubt, COVID-19 has changed the threat landscape," says Peggy Hamburg, former FDA commissioner and now vice president of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a nonpartisan think tank on global security.

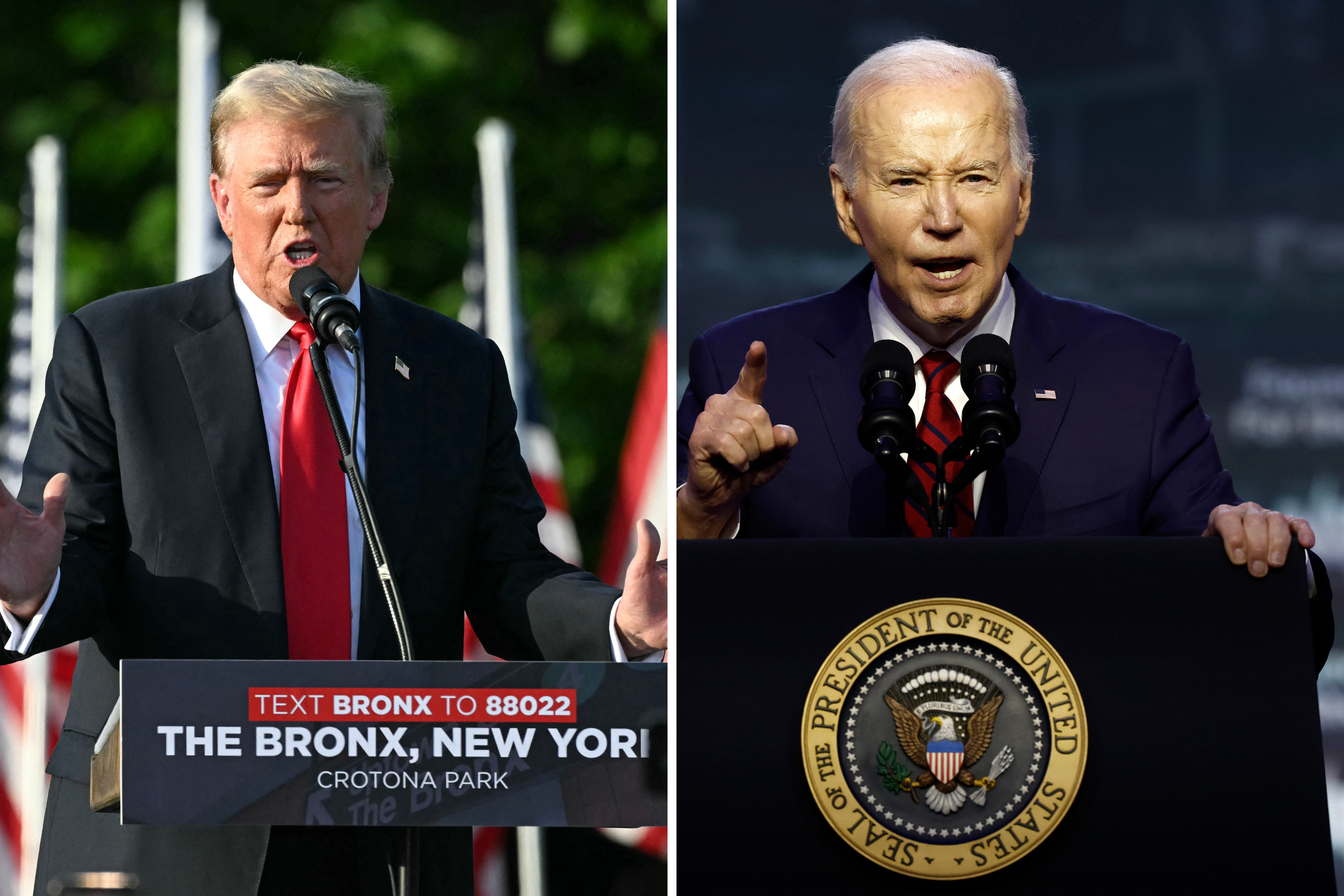

Yet despite the rising risk of a new, future pandemic caused by a lab leak—or one that emerges from a bioterrorist attack or even natural causes, for that matter—the U.S. government, under the leadership of Joe Biden and Congress, seems on course to repeat the mistake made by nearly every one of its predecessors for the past several decades: failing to take all possible steps to strengthen America's response to a future pandemic or prevent one from happening in the first place.

One year ago, as SARS-CoV-2 raged through an unprotected population and vaccines were still months away from authorization, workers were wondering how they'd protect themselves through the long winter months and parents were fretting over how they'd hold down a job while their kids stayed home all day learning in front of a laptop. Now, despite the widespread availability of vaccines, the surge in COVID cases due to the Delta variant is raising fears and uncertainties about the prospects of a second pandemic winter among a war-weary public.

The upside of a nation of people bummed out about new mask mandates and public health restrictions for another school year is a rising understanding of how much pandemics suck and how important it is to prevent them. With the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic still in full swing, public awareness should be at a historic high. One poll, by the progressive group Data for Progress, shows that 71 percent of the public—including 60 percent of Republicans—supports a $30 billion pandemic-prevention plan recently floated by President Biden.

The White House's plan hits the right notes. It would improve response time to develop therapeutics and vaccines, beef up the national stockpile and tighten regulations on risky lab research. But just because Biden proposed it doesn't mean Washington politicians are tripping over themselves to implement it. The bipartisan infrastructure package did not include funding for the plan, and it's not clear the $3.5 trillion spending bill that Democrats hope to pass without Republican support will include that money, either—Democrats are reportedly considering paring down funding to 20 percent of the original proposal. On this omission, Biden has so far been silent.

Having resources to regulate hazardous research may be critical. "The discussions about the Wuhan lab underscore that this is a theoretically plausible risk—that there could be a global pandemic that emerges because of work going on in a laboratory," says Dr. Hamburg. "We may never know the origins of this particular virus, but it shines a very bright light on the need to address some broader, very critical biosecurity concerns."

Slow Learners

Keeping the world safe from deadly pathogens isn't something the U.S. can do alone. But the top levels of the executive branch need to ride herd on the disparate departments and agencies of the federal government to prevent a crisis and respond when one occurs.

Past presidents have learned and unlearned this lesson many times. President Bill Clinton appointed a team headed by Kenneth Bernard, a medical doctor and rear admiral, to the National Security Council in 1998. Bernard's office helped coordinate the response to the HIV/AIDS crisis and was instrumental in establishing a national stockpile of vaccines against smallpox, neutralizing the smallpox virus as a potential bioweapon. But George W. Bush eliminated the office early on, only to reverse course after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, when anthrax-laden envelopes started arriving in the mailboxes of prominent politicians and media organizations. A year or so later, Tom Ridge, head of the newly formed Department of Homeland Security, brought Bernard back as part of a five-person White House biosecurity team.

The H1N1 influenza pandemic arrived in the early days of the Obama administration, before Kathleen Sebelius could be confirmed as head of HHS. As a result, it was criticized for being slow in developing a vaccine and for its public health messaging. The mildness of the H1N1 virus let the Obama administration off the hook.

Still, when the Ebola crisis arrived in 2014, the Obama White House was caught flat-footed. After being criticized for a slow response, Obama tapped Ron Klain, former chief of staff to vice-presidents Biden and Al Gore—and now to President Biden—to take a high-profile role coordinating the U.S. Ebola response.

Klain coordinated the disparate departments and agencies of the federal government. The White House ultimately sent thousands of troops to the front line of the epidemic in West Africa to help contain the outbreak. "I was brought in not because I knew about public health or pandemics but because I had experience in making the different arms of the government work together and making them work effectively and quickly," Klain told Wired in 2015. "That really was the challenge—coordinating between the different agencies.

That lesson was codified after the crisis was over by a junior member of the White House staff named Beth Cameron, who helped draft the Obama playbook for use in future pandemics. Among its recommendations: Create a permanent pandemic office in the White House's National Security Council—a pandemic czar who would sound the alarm about a biological threat long before most White House officials, distracted by myriad day-to-day problems, would typically notice, and then wield the enormous power of the office of the president to force the vast federal bureaucracy to focus on an invisible threat and take swift action.

Obama followed this advice, appointing Admiral Timothy Ziemer, a veteran of AIDS and malaria programs in Africa. Ziemer stayed through the first half of the Trump administration only to be fired in 2018 by John Bolton, the new national security adviser. Bolton disbanded the staff and shifted responsibility for coordinating pandemic response to HSS.

When news of COVID-19 started coming in from China in early 2020, there was no pandemic czar on the White House staff to galvanize the pandemic response or point out how important it was to push China to be more forthcoming with information on the outbreak's origins. "The problem with Bolton eliminating the office was not so much that he disbanded the team but that he fired the pandemic czar," says Bernard. "If you can't advocate for an issue with the boss with a walk-in-the-office mandate, then you are, by definition, lower priority."

Ziemer insists that Bolton's reorganization made sense but allows that a pandemic czar would have helped. "Had I been there," he says, "I'd have been pounding on [chief of staff] Mick Mulvaney's desk saying I needed $8 million to fund this team."

Biden acted quickly upon taking office to correct this omission. He appointed Cameron, the author of the pandemic playbook that Bolton ignored, as head of the National Security Council Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense. Cameron is charged with establishing a U.S. center that will act as an early-warning system for disease outbreaks, reduce the time that it takes the government to respond to new biological threats and to review "the existing state of our biodefense enterprise and [determine] where gaps remain," according to a senior government official at the White House. "We must urgently prepare for and ultimately try to prevent the next pandemic by strengthening biopreparedness at home, bolstering health security in every country, and building the international pandemic architecture we need to prevent, detect and rapidly respond to emerging biological threats." (Cameron declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Biden gets high marks for his appointment of Cameron from Bernard and Ziemer. "It shows that the Biden administration gets it," Ziemer says. Gerald Epstein, a physicist who worked in national security in the Clinton administration, says "the White House has hit the ground running and has great people." He calls the Biden plan "ambitious."

The pandemic czar now faces a daunting task. She will have to find a way to effectively regulate the most risky research performed in the U.S. labs and those financed by the U.S. government, many of which take place abroad. And she will have to push to get the commitment of other nations to follow suit and to agree on international mechanisms to monitor for outbreaks and investigate them once they occur.

What to Do About Risky Lab Research

Scientists and policymakers have been issuing warnings of the risk of a pandemic starting with a lab accident for many years. The history of accidents in U.S. labs that perform research with dangerous pathogens, with poor safety practices and minimal oversight, has been well documented.

Cracking down on this research will be tricky, not least because the federal government is not in the habit of policing the work of research virologists, who in turn are understandably reluctant to be policed. For the vast majority of research, this is not a problem. For a tiny portion of research, it is—and all it takes is one incident to start a pandemic.

In recent months, the argument over whether the pandemic started with a lab leak or arose naturally from animals has taken on the characteristics of a schoolyard shouting match—two sides each insisting they're right on the basis of little or no evidence. We may never have clear evidence either way.

Settling the matter would require the discovery of compelling new information—either a genetic trail from bats to humans via some intermediate mammal—a so-called zoonotic origin—or lab notes and interviews with researchers and other employees of the Wuhan laboratories, which could happen only in the event that those records have been retained and that China chooses to cooperate, or copies of those records exist at the Wuhan lab's U.S. collaborators, funders or publishers and that the U.S. chooses to investigate. The 90-day intelligence report that President Biden has requested is not expected to reveal a smoking gun or even anything profoundly new.

What's needed are standards of biosafety for the research on pandemic viruses that could result in trouble if a lab leak occurred—not so much a ban on risky research as an effective system of regulation that would require a consideration of benefits versus risks at the outset of research, says Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers and an expert in biosafety. "This would be put in place for high-consequence research—research that increases the transmissibility, or pathogenicity, or ability to overcome immune response, or ability to overcome drugs or vaccines of a pathogen," he says.

The current structure of oversight is inadequate, says Ebright, mainly because the funding agencies police themselves. After a moratorium on research that involves increasing the infectiousness or virulence of potential pandemic pathogens, in 2017 the federal government required the HHS to establish a committee to review proposals for such "gain-of-function" research to determine whether the benefits outweigh the risks. It also required the NIH and other funding agencies to flag such proposals to the committee. The committee cleared three proposals, says Ebright, after which no further proposals were flagged for review, essentially nullifying the policy.

Instead, analysts say, oversight should fall to an independent group that can assess the benefits and risks objectively. "It has to be carried out by a federal entity that does not perform research and does not fund research, with expertise in national security issues, biomedical research and formal quantitative risk-benefit assessment," says Ebright. "And it has to be carried out by an entity that is open and transparent in its membership and its proceedings."

The process would be similar to what now occurs with research involving human test subjects. If risks are found to outweigh the benefits, the research is not simply denied funding. It isn't allowed to proceed at all.

Processes are also needed to deal with the pandemic threats posed by bioterrorism—and by nature, which has shown itself perfectly capable of delivering diseases even nastier than COVID-19. For proof, one need look no farther than smallpox, which kills 30 percent of its victims. Inexpensive genetic tools have made it relatively easy and cheap to manipulate viruses like smallpox to resist vaccines, and even manufacture new viruses from scratch.

An International Response

To prevent an accidental pandemic, it's not enough to get a grip on U.S. research. The Biden administration will have to use its leadership abroad to establish international biosafety standards. It will also have to get other nations to agree to standards of behavior in a crisis, including sharing information about outbreaks and agreeing to allow international inspectors to gather information in the early days of an outbreak.

Cameron is well aware of the need for such agreements. Prior to her appointment in the White House, she was an organizer of an exercise held in 2019 in Munich designed to identify shortcomings in the world's biosecurity. For a few days, she and a broad range of experts from several nations held war games that focused on "deliberate high-consequence events"—in a word, biowarfare. The group wanted to assess how well the U.S. and the rest of the world would fare if, say, a terrorist group were to release a dangerous pathogen on an unprotected population.

The group started with an outbreak of a respiratory ailment in the fictional country of Vestia, riven by civil war. Medicines turn out to be ineffective against the pathogen, Yersinia pestis, a plague bacteria engineered by a terrorist group to resist known antibiotics. The outbreak spreads to Europe and the U.S. The director-general of the World Health Organization declares a public health emergency.

It's not exactly how the COVID-19 pandemic transpired a year and a half ago, but it's similar in many respects. It makes little difference whether or not SARS-CoV-2 was natural or engineered or whether it was deliberately or accidentally released. In both the tabletop scenario and the real event, the pathogen was novel, meaning the nearly 8 billion people on Earth had no immune resistance to it, and there were no known treatments or vaccines against it.

The other similarity between the game and the reality is that the world was woefully unprepared and cumbersome in its response. Having lived through the current pandemic, it's not hard to understand the reasons why: Nations are unwilling to share information and forced to cobble together an ad hoc response and governments lacked transparency and consistent messaging. One prominent obstacle the tabletop exercise didn't foresee was the hyper-politicized environment of public health measures, but two out of three ain't bad.

When the pandemic struck in late 2019 and early 2020, the international scenario played out as poorly in real life as it did on the tabletop. China snapped shut like a trap, silencing clinicians who sounded the public health alarm and destroying early samples that could have helped trace the origin of the virus. The World Health Organization, which the Trump administration had recently abandoned, was left to deal with a situation that was beyond its capacities and its mission.

What the world needed at that moment was a "joint assessment mechanism to investigate high-consequence biological events of unknown origin," says Jaime Yassif, a senior fellow for global biological policy and programs at NTI, who worked for Cameron at the time. That would be an independent agency of the United Nations similar to the International Atomic Energy Commission, which oversees agreements on nuclear proliferation, including supplying inspectors to police the nuclear agreement with Iran.

Had China, the U.S. and other nations put such a group in place prior to early 2020, a team of investigators with the ability to explore the "naturally emerging" and "lab accident" hypotheses would have been at the ready, along with international agreements and protocols to smooth their way in gathering information, working with a network of labs to evaluate samples and conduct a thorough investigation. They might have explored, in a scientific, evidence-based way, all the open questions about origins. The U.S. would have had a way of rapidly deploying an investigative team to get more reliable information about the origins and try to understand the cause.

As it was, the void was filled by the WHO, whose mission is to investigate natural outbreaks. Any notion that the WHO was equipped to investigate the possibility of a lab leak is belied by the fact that it took a year to send a team of investigators, who came to the dubious conclusion that no further investigation into the lab-leak theory was warranted—a claim later contradicted by the U.N. Secretary-General.

Had the outbreak clearly been a biological attack or other deliberate misuse of biological agents, the responsibility for investigating could have fallen to the Secretary-General, under the auspices of the bioweapons convention. Because the origin of the outbreak was ambiguous, it fell through the cracks.

With no responsible organization in place to take action at the moment of crisis, a yawning information gap opened up. It was quickly filled with finger pointing, racism and conspiracy mongering, particularly in public exchanges between the U.S. and China. "If we had had a mechanism in place," says Yassif, "perhaps we could have avoided a lot of the uncertainty and politicization of this question, and perhaps we could have gotten a higher confidence assessment of the origins early on."

That assessment, of course, is hypothetical: There's no guarantee China, even were it to sign on to such a mechanism, would honor it at the moment of crisis. But even so, it would have had to commit a clear violation of a standard of behavior that it had agreed to. The fact of noncompliance would itself have been useful information.

Now that the world has seen what havoc can result from a nasty bug, says Yassif, "they may be more interested now than they were in the past of exploring the prospect of using biological weapons to advance their strategic or tactical aims. It's getting easier and easier for malicious actors to theoretically carry out a biological attack deliberately. COVID has highlighted these risks and may even have exacerbated them."

A Question of Leadership

To have a chance at getting all this done, the pandemic czar has to have a laser-focus on the issue of pandemic preparedness as well as the full support of the president of the United States. The key question is, will Cameron get the support she needs to shake up the administration?

The role of a pandemic czar is as much about national security and policy as it is about science. Questions about closing schools and airports, implementing mask mandates and closing businesses are political decisions that can only be made by somebody who has the ear of the president, as Ron Klain did during the Ebola crisis. It's not clear, says Bernard, that Cameron has that kind of authority.

"Before they named Klain during Ebola, it was a disaster," recalls Bernard. "Our response was disjointed and stovepiped. Defense wasn't talking to Health and Human Services. USAID was arguing with CDC. It was a mess—and then Ron came in and pulled everybody together. That's what's needed. That's what's missing even today at the White House."

The task requires a leader who can act in the president's name and get senior people from all departments of governing to come to the table. The lack of clear authority has hampered pandemic responses not just during COVID-19 but in other outbreaks as well. A pandemic response requires high-level-policy meetings with the Defense Department, State Department, Health and Human Services, USAID, the Treasury and Commerce.

"They all have to be in the room because if they're not, you miss something because they're all interrelated when it comes to a global pandemic," says Bernard.

Cameron's rank in the White House is Special Assistant to the President. This sounds impressive, but it's lower in the hierarchy than Press Secretary or National Security Adviser, who are Assistants, and lower than Deputy Assistants. Bernard says it is "not senior enough for running a U.S. government-wide process."

The highest ranking science adviser in the White House is not Cameron but Eric Lander, the first science adviser to hold cabinet rank. Lander has a reputation as a brilliant scientist and administrator and has assembled a highly-regarded staff. As the former head of the Broad Institute in Boston, Lander knows as much as anybody about the science and is known to be pushing for better oversight of research on risky pathogens. But as head of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, his responsibility is far broader than preparing for the next pandemic, which means he lacks the single-minded focus a pandemic czar needs.

Even if Cameron gets the full backing of Biden, Ziemer worries that COVID-19 has been so politicized that it will be difficult for the Biden administration to get anything done. "The current government bureaucracy, the inability to move money quickly in response to a changing landscape, will keep the government handicapped on where we need to go in the next five years," he says. "We need to depoliticize COVID and have an adult discussion about how to plan, fund and remain agile in preparation for the next pandemic."

So far, Biden has taken few steps to address the next pandemic. He made public statements calling China to task for its lack of transparency over the origins of the virus. He signed an executive order to create a center for epidemic forecasting and outbreak analytics that would track viruses and watch for early signs of an outbreak in the U.S. And Cameron is reaching out to other governments to talk about cooperation.

If history is any guide, now is the moment of maximum political will to prevent and prepare for the next pandemic.

The failure of the U.S. government, and those of other nations, to prepare for the possibility of a sudden, catastrophic pandemic—something scientists had warned about for years before the coronavirus struck—arguably cost millions of lives, trillions of dollars in lost wages and ruined livelihoods, and immense human suffering. It would be unthinkable to allow that to happen again.