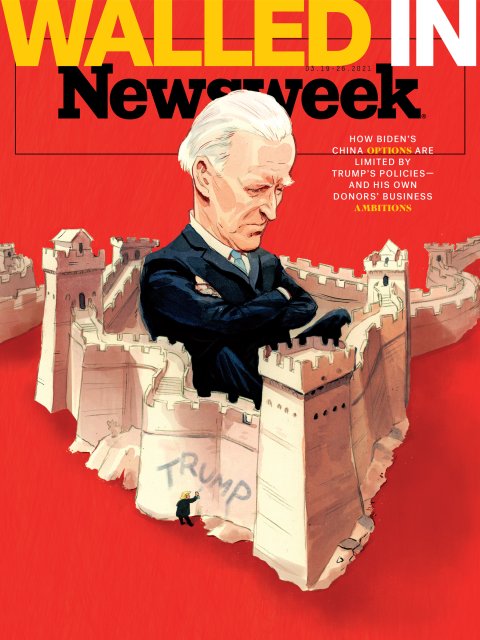

What would Joe Biden do if he had to choose between pleasing his political donors or endorsing a key Donald Trump policy? Well, obviously he's going to...wait a minute. He what???

On the most consequential foreign policy issue that the Biden administration is likely to face—how to deal with the People's Republic of China—the new Democratic president seems ready to follow the path set out by his Republican predecessor.

"Let me just say that I believe that President Trump was right in taking a tougher approach to China," said Antony Blinken, Biden's secretary of state, during his confirmation hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in January. Then, before the shock of that statement could sink in, he quickly added: "I disagree very much with the way that he went about it in a number of areas, but the basic principle was the right one, and I think that's actually helpful to our foreign policy."

It is hard to overstate what a sea change there has been in Washington foreign policy circles over the last four years—a change driven, as Blinken acknowledged, by Donald J. Trump.

Since Richard Nixon established relations with the People's Republic of China in 1972, U.S. policy has consistently sought to integrate Beijing into an international order built by Washington in the post war era—to help it become a "normal" country. When Deng Xiaoping began opening China's economy to the world in 1978, the U.S. relied on trade and investment as the principal tools to bring China into the world and help make it, in the words of former Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick, "a responsible stakeholder." Successive administrations, from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama, effectively stayed on the same course. The U.S. policy toward Beijing was that of "engagement," and economics was its lynchpin.

Then came Donald Trump. Elected in part because swaths of the industrial midwest had been devastated economically by low-cost Chinese imports, Trump vowed to stop Beijing, as he repeatedly stated on the campaign trail, "from ripping us off." To the dismay of the American foreign policy community and the Fortune 500, he dismantled the free trade status quo with Beijing. He slapped significant tariffs on Chinese-made goods, sought to limit Chinese investment in key U.S. high-tech industries and tried to block high-profile Chinese companies such as Huawei not only from the American market, but from those of key allies as well.

Now, many of Biden's key constituencies would love to turn back the clock. From Wall Street to Silicon Valley to Hollywood, they remain understandably fixated on the massive—and still growing—Chinese market. But the early signs from the new administration are that they are likely to be disappointed.

In his confirmation testimony, Blinken forthrightly called relations with the PRC "the greatest foreign policy challenge of this century." The question facing him and the Biden administration is, what are they going to do about it?

The answer, gleaned from numerous interviews with people inside the Bidenadministration (and outsiders who have spoken with them about China), is: They're not quite sure yet. "It's definitely a work in progress," says a senior Pentagon official who will participate in a formal review, announced on February 24, of the U.S.'s defense posture toward the PRC. The official, who is not authorized to speak on the record, requested anonymity.

That shouldn't be surprising. The challenge of confronting a rising China makes the first Cold War, against the Soviet Union, seem like a relatively simple affair. Beijing, unlike Moscow, presides over an increasingly large, technologically sophisticated economy. The size of its market seduces companies from all over the world. Despite pleas from the Biden transition team to wait, the European Union on December 30 signed a broad investment treaty with Beijing that was seven years in the making. (The European Parliament still must ratify the treaty—not necessarily a given.) Within a couple of decades, the PRC will be the world's largest economy, and Beijing openly seeks to dominate key sectors of the 21st century economy, from artificial intelligence to quantum computing.

At the same time, it is expanding and modernizing an increasingly capable military, and is already a "near peer competitor" (in Pentagon-speak) in the Indo-Pacific region. Beijing may not yet pose as grave a nuclear threat as the Soviet Union did—it has far fewer nuclear warheads than Moscow did at the Cold War's peak—but its economic success, increasing technological sophistication and global ambition make it a more formidable foe than Moscow ever was.

The Pentagon is already concerned that the U.S. risks falling behind the PRC militarily. The former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Joseph Dunford, told Congress that "in just a few years, if we do not change our trajectory, we will lose our qualitative and quantitative advantage relative to China." Former Undersecretary of Defense under Obama, Michelle Flournoy, says defense spending going forward "will require a lot of investment in new technologies and capabilities that are not yet in the U.S. military."

They include everything from effective defenses against China's hypersonic missiles—which would be crucial in any conflict over Taiwan, for example—to an increasingly prominent role in combat for artificial intelligence and what military analyst Christian Brose, former staff director of the armed services committee, calls "intelligent machines," which can aid in identifying objects on a battlefield, navigation, and a host of other non-lethal applications.

Biden's people acknowledge the challenges. For now, in public, they are all singing from the same hymnal. The president himself said the U.S. will engage in "extreme competition [with Beijing], but there need not be conflict." (Early in the presidential campaign Biden had famously—or infamously—derided the notion that China posed a threat to the U.S: "They're gonna eat our lunch? C'mon, man!")

In his "extreme competition" speech, Biden did try to distance himself from Trump's approach, saying "we're going to focus on the international rules of the road." But the president is in a box when it comes to China. It is a box constructed by the outgoing administration on the one hand, and some of his biggest campaign donors on the other—donors who wish nothing more than to wish away the last four years.

They pine for the days when top U.S. government officials gave speeches describing China's "peaceful rise." They'd like to engage in diplomatic exercises like the "strategic economic dialogues" of the past—biannual gabfests among senior officials from Beijing and Washington, started under George W. Bush and continued under Barack Obama. That continuity exemplified how both political parties in Washington had come to view relations with Beijing through the same set of glasses—rose-colored ones.

Wall Street, the C-suite in most Fortune 500 companies, Big Tech and Hollywood were among the biggest donors to the Biden campaign. At JP Morgan and Bank of America, for example, more than 7,000 employees at the two firms combined donated to presidential campaigns—more than 80 percent of them to Biden, for a total of more than $200,000. At Google, 6,900 employees donated, 97 percent of them to Biden. Amazon: 10,000 employees gave money to a presidential candidate, 80 percent of them to Biden. In Hollywood, 4,100 Disney employees gave to presidential campaigns, 84 percent to Biden. Altogether the TV, music and movie industries gave $19 million to the Biden campaign, and just $10 million to Trump, the Center for Responsive Politics reports.

All have long had a keen interest in doing business in China (even if the so-called "Great Firewall'' keeps out some tech companies like Google and Facebook). All now have an interest in how the Biden administration defines what "extreme competition" will look like. "No one is naive enough to think we can just go back to the halcyon days of 'strategic engagement,'" says Scott Harold, a senior political scientist focused on east Asia at the Rand Corporation. "But will there be some pressure to be less confrontational than Trump was? Sure."

It's already clear to Team Biden that making that adjustment will not be easy. On their way out, Trump's people fanned the flames on two of the most contentious issues between Beijing and Washington. On January 19—the day before Biden was sworn in—then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that China had committed "genocide and crimes against humanity" by repressing Uighur Muslims in its Xinjiang region. The assertion arguably brought relations between the two countries to a post-Tiananmen Square low. Biden's key foreign policy advisers—national security adviser Jake Sullivan, Indo-Pacific coordinator Kurt Campbell and Blinken—were angered by the declaration's timing, sources close to all three told Newsweek. (The sources were granted anonymity in order to speak candidly.)

International human rights attorneys are divided as to whether Beijing's internment of Uighurs is, in fact, genocide under international law, and Biden's team wanted to make an assessment for itself. But to disagree publicly right out of the gate would inevitably prompt charges from Republicans that Biden was "weak" on China. Thus, the day after he was sworn in, Blinken said he agreed with Pompeo's designation.

That caused indigestion in some key Democratic precincts. The pro-China business constituencies have for decades lobbied previous administrations to sideline human rights as an issue. And nearly always, they got their wish. Early on in the Obama administration, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton publicly said human rights "can't interfere" with other, more pressing issues with China.

Times have changed. A veteran lobbyist for a major Wall Street investment bank told Newsweek, "It's unclear as to what exactly these guys are thinking about how much to emphasize human rights, but I think everyone's starting to realize it's going to be more than in the past." Most of Biden's key China advisers—Sullivan, Blinken, Kurt Campbell and U.S. Trade Representative nominee Katherine Tai—worked at various times in the Obama administration.

The use of the word "genocide" put the administration in a bind. As the Wall Street lobbyist—who asked not to be identified in order to speak openly—put it, "You can't accuse another government of 'genocide' and then do nothing. There have to be consequences. So will there be more [economic] sanctions now? And won't that trigger a response from [Beijing?] And tell me how this is different from Trump?" A senior official in Biden's National Security Council concedes, "'Those are all questions we are dealing with."

The other hot button issue Team Trump left behind is the mystery of where and how the COVID-19 virus originated in China—and what, if anything, the West should do in response. Again on his way out the door, Pompeo raised the possibility the virus might have escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, and that in the fall of 2019, several researchers at the lab had come down with COVID-like symptoms.

On January 13, a team of researchers from the World Health Organization—which the Trump administration had pulled the U.S. out of, accusing it of being lackeys for Beijing—entered Wuhan in order to investigate what had happened there. The Biden team had quickly rejoined the WHO as a symbol of the United States being back to playing a key role in international institutions. It pledged to resume its annual dues of $200 million a year to the WHO.

Then the WHO embarrassed itself and, by extension, the Biden administration. It concluded its "investigation" into the virus origins without seeing critical data from the WIV lab. Former Trump administration officials assert that Chinese officials have been scrubbing data from the earliest stages of the outbreak related to the virology lab. Yet the WHO's team stated conclusively that COVID-19 didn't start there and floated a theory that the virus arrived on packages of imported frozen food.

The hurried investigation and subsequent WHO press conference were a fiasco. NSC adviser Sullivan had to issue a statement saying the Biden administration still had questions about how the WHO had come to its conclusion, and called on Beijing to provide more data from the outbreak's early days. In other words, he sounded pretty much like Mike Pompeo. Asked for his reaction to the WHO investigation, Biden tersely responded, "I need to get the facts."

Those two immediate controversies overshadowed the other, major issues Beijing poses for Biden. One is economic: whether, and to what extent, to continue to "decouple" from China. Trump while in office, had pushed this theme, particularly in the wake of COVID-19, when he demanded that all personal protective equipment like face masks be made in the USA, not in China. But the effort to push U.S. multinationals more broadly to divorce themselves from China has been ramshackle and, thus far, not very effective. Congress passed a law in 2019 calling for U.S. defense and telecommunications companies to strip Chinese-made hardware and software from their supply chains. But progress has been halting, because removing the China-sourced equipment is proving far more difficult than Washington understood. It is also costly to any number of critical industries. A recent study by the Rhodium Group, a D.C. research group, estimates that loss of Chinese customers would cost the U.S. semiconductor industry $54 billion in annual sales.

Many companies have spent years building out their supply chains in China and are loath to give them up. And in the meantime, says a telecom industry executive who was granted anonymity in order to be candid, "nobody was watching too closely to see just how far these Chinese components and hardware have infiltrated U.S. businesses."

But the multinationals hoping that Biden might give them a pass may have misplaced their hopes. On February 24, Biden signed an executive order that included a reassessment of supply chains in key industries, including semiconductors and advanced batteries. In the announcement, the administration also said it will work with allies Japan and South Korea in an effort to persuade their companies to relocate supply chains from China.

Aside from occasional public rhetoric, the Trump administration did not emphasize working with allies when it came to decoupling. Seoul and Tokyo will be happy to have those conversations, but the extent to which Japanese and South Korean companies are willing to disengage is at best uncertain. Their economies are now far more intertwined with China's than the U.S. is. As the Rhodium Group's report says, U.S. competitors might just as soon snap up Chinese customers if U.S. firms leave. But whether allies play along or not, it's clear the pressure on U.S. companies is not diminishing under Biden. At least for now.

Biden has also disappointed his Wall Street and Fortune 500 backers by leaving in place Trump's $250 billion in tariffs on Chinese exports. Trump had promised to reduce or eliminate the tariffs in return for increased Chinese purchases of U.S. goods and agricultural products, which Beijing committed to in a deal signed in January 2020. But Beijing has not complied: its purchases are far short of promised, and Biden's team is now mulling how to enforce the deal. That's why, for the moment, a removal of the tariffs is off the table. "We can't just remove them having gotten nothing in return," the NSC source says.

The second critical area for Biden's China policy is the just-announced defense review, the results of which appear foreordained. Biden's Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has signaled that the new administration, like its predecessor, views China as the principal military and geopolitical threat to the U.S. The Biden administration appears to share the belief that Beijing seeks to force the U.S. out of the western Pacific, and to dominate the South China Sea. Washington also wants to be sure the U.S. has the firepower and manpower in the region to deter Beijing from making a move on Taiwan, which the PRC regards as a renegade province. A White House source, granted anonymity because the source was not authorized to speak on the record, says Biden, in his recent two-hour phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping, spent "considerable time on Taiwan. He's well aware of what a real flashpoint it is."

Logically, all of this would lead to sending more troops to the Asia Pacific, and greater investment in technologies to counter China's strengths—for example, defense systems that could shoot down hypersonic missiles. Trump sought both, but never really delivered on either.

The potential problem for Biden is, the U.S. is entering a period in which already huge budget deficits are set to explode to unprecedented levels if the administration's $1.9 trillion COVID relief bill passes.

The Pentagon's longer-term fear, says the source participating in the defense review, is that it will inevitably come under pressure for cuts in spending in the next couple of years. That was true even before the pandemic. The source half-jokingly says he worries that the Biden "pivot to Asia" will end up being as inconsequential, militarily, as was Obama's. Despite much fanfare about the "pivot," only a handful of troops ended up redeployed to Asia (the bulk of them, 1,150 Marines, to Australia). "Everyone around here suspects that the [budget] axe is going to fall at some point," says the Pentagon source.

Blinken plainly wasn't kidding when he said he approved of Trump's tougher approach to China. On trade and on defense, Biden's approach so far is more of the same. As far as the details of the previous administration's approach that he said he quibbles with, they come down to two things. Biden will work more energetically with allies to confront China on trade and deter it militarily. The other difference is the eagerness, despite tension in the relationship everywhere else, to work with Beijing on climate change.

Trying to persuade Beijing to reduce its CO2 emissions—by far the most in the world annually—is a nice goal. Why Beijing would play along now is entirely unclear. Climate czar John Kerry has said the world has been starved of U.S. leadership on the issue. The truth is, Beijing has never had any interest in US "leadership" on climate, and it still doesn't.

But given how potent the issue appears to be among the new Democratic party—Biden was willing to anger union workers on the Keystone pipeline in order to assuage climate-obsessed supporters—Beijing may use the issue to try to get what it wants elsewhere. It may promise an emissions cut here or there, or agree to partner on some "green" energy research projects, in return for dropping tariffs or a general de-escalation of the ongoing economic wars.

That's not a deal Trump would have made. But just a month into Biden's term, it should already be clear to his donors—Wall Street, Big Tech and Hollywood most prominently—that this president can't just snap his fingers and pretend it's 2010 again, when U.S. policy was all about "engagement" and a market of 1.3 billion consumers beckoned beguilingly.

Key signals for what Biden's China policy will look like? When (or if) the administration decides to maintain indefinitely the Trump tariffs if China does not step up its purchases of U.S. goods and services; how the now-underway defense review will alter U.S. military deployments in east Asia; whether the new president will try to revive a version of the Trans Pacific partnership—a trade agreement among U.S. allies that the Obama administration never submitted to Congress for ratification. That would be a powerful signal to Asian allies that Biden is serious about working with them to expand trade and contain China, which the treaty excludes.

Biden and his team have already shown they are realists, not romantics, when it comes to China. And the reality they are bending to is one Donald Trump helped create.