"OK, Boomer" is what younger people say when they want to dismiss boomers as being out of touch or stuck in our boomer ways, sort of this generation's version of "If you say so, old-timer." It's not exactly an ageist insult, but it sure ain't a compliment.

Fine. OK. We get it. Have fun. But remember one thing before slinging insults: The world, according to Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker (and many others), is better off now than it's been at any time in history. That's right. Ever. And I contend it's because of boomers. Boomers are the greatest generation the world has ever known. The most innovative. The most caring. The hardest-working. That may seem a bit much, but to quote the pitcher Dizzy Dean, "It ain't bragging if you can back it up."

Millennials seem to think their challenges are greater than those any other generation has faced. Not really. The Great Recession? Nothing compared with the Great Depression (although the way the markets have been behaving lately, you may get there yet). The wealth gap? Today it's actually pretty close to historical averages, and nowhere near the peak that occurred at the end of the 1800s, research shows. Student loans? Student loan debt is $1.6 trillion. Over the next 30 years, boomers will pass down $68 trillion as part of the "Great Wealth Transfer." That should cover it for many borrowers (the timing may suck, though).

There's more. Opioids? We had heroin and crack. Good jobs? They weren't that easy to come by for us either. We were the population pig-in-the-economic-python. Competition was fierce. Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell? We had Richard Nixon, George Wallace, Lester Maddox and Richard Daley. What about the fact that boomers get an outsized proportion of government benefits such as Social Security and Medicare, what some call boomer socialism? Well, that's true—but would millennials rather we went back to the old system where the older generation lived with their adult kids who cared for them? Didn't think so. Oh yeah, we also had the Vietnam War and the draft.

This is not to say that your generation doesn't face problems or that they're not important. Some, like artificial intelligence (AI), climate change and the redux of autocracy, rise to the level of existential. The hard truth: Every generation faces existential crises. You think the bubonic plague and AIDS weren't existential crises? How about Hitler? Or communism? Boomers lived under the very real threat of a nuclear war that would have killed everything and turned the planet into a ball of ice. In 1962, Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring about the global poisoning caused by pesticides. In 1968, professor Paul Ehrlich of Stanford wrote The Population Bomb, which predicted worldwide famine in the 1970s and 1980s due to overpopulation. And in 1972, the Club of Rome published The Limits to Growth, which predicted that the world would begin running out of resources by 2008.

of those happened. Know why? Because we dealt with them, that's why. During the century before Ehrlich's book, almost a million people starved each year. Since? About 200,000 a year. That's still too many, but it's a huge improvement. We dealt with those crises and cleaned up some of the messes previous generations had left us, like depletion of the ozone layer and the nicotine epidemic. And here's another insight. You will too. You will manage it because you are the smartest, healthiest, best-educated, most enabled generation in human history. You are what evolution has been working hard for 200,000 years to produce.

And it's a good thing you're so well prepped, because it's your turn now. Last year, millennials passed boomers to become the population's largest segment, the Pew Research Center says. About half of boomers have already retired. It's time for us to step off the stage and for you to step up.

Let's see how we did and what you'll have to live up to, using 1969 as a benchmark, when leading-edge boomers were 23, the same age as the youngest millennials are now. Spoiler alert: The world we're leaving you is way better off than the one we got.

Wealth & Income

Millennials are justifiably outraged over the growing wealth gap. Here's what gets lost, though. While the average person may be slipping further behind the wealthy, they are still better off in absolute terms than they were 50 years ago, in income and net worth. Median household income in 1969 was about $68,000 in today's dollars (adjusted for inflation). Today, it's slightly lower, $64,000, even though there's been a rise in two-income families. But households were larger then. Per person, each of us has about 20 percent more income than a typical person did in 1969.

Taxes are much lower now than they were in 1969. Overall, things are cheaper. While health care and education costs have risen faster than inflation, many everyday items have become much less expensive. A round trip New York–London air ticket cost $550 back then, about what it costs now. But once inflation is considered, that $550 ticket would cost over $3,700 in today's dollars. The cheapest color TVs cost the equivalent of $3,000, which is why only one in three homes owned one.

Best of all is phone usage. In 1969, according to Federal Communications Commission data, rates varied by location, distance, time of day and type of call (business vs. residence). A typical 10-minute chat cost about $15 in today's dollars, and much more if the location was more than a few miles away. These days, the average person spends almost three hours a day on their phone—calling, texting, browsing, etc.—so your cellphone bill would be about $8,000 a month if you were paying the usage rates we paid. You may still be broke, but you're surrounded by better stuff.

Security & Safety

There's a large industry out there working hard to scare you. News media looking for clicks. Burglar alarm companies looking for business. Politicians looking for votes. And it's working. According to Pew, most Americans feel the world is getting more dangerous each year. But it's not. It's actually getting safer, FBI data show. In 1969, the murder rate was about 70 people per million vs. 50 now. The burglary rate was 9,841 vs. 3,760 now, a 62 percent drop.

The only number that's really up is rape, which has more than doubled to 420 per million. But that jump needs some context. Back in 1969, less than one-third of rapes perpetrated by people known to the victim were reported. Now that number has more than doubled. Survivors may also be better able to identify assaults as crimes due to cultural changes like the #MeToo movement, the National Sexual Violence Resource Center has noted. So at least some of the increase may be because we're counting better.

Crimes of violence are horrible but not common. What's really dangerous: cars. A typical person is four times likelier to die in a car than be murdered. Car deaths have been plummeting: In 1969, over 50,000 people died in car accidents, one for every 1 billion miles driven. In 2018, even with the added danger of texting while driving, the number was 36,560, or one for every 3 billion miles. That's due to both safer roads and safer vehicles, as well as mandatory seat belt laws.

Health & Longevity

The average person today lives to be 79 years old, eight years longer than in 1969. Some of that is because smoking has declined. About 40 percent of the population smoked back then; it's down to 15 percent now. Some of the gain is because of better health care. Many of the diseases that affected us, like polio, are no longer an issue because of vaccinations. Five-year cancer survival rates are up too, from around half to over two-thirds.

And although it's harder to quantify, it's also almost certainly a better-quality life because lifestyles and nutrition are better. To millennials, for whom Orangetheory and SoulCycle are a way of life, it probably seems strange, but people didn't really bother to stay fit back in 1969. Running didn't take off until the early '70s. Nike wasn't even making running shoes in 1969. Fitness classes didn't become popular until the 1980s. To be fair, although boomers have taken fitness to where it is today, we didn't start it. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson launched the Presidential Physical Fitness Test, which resulted in millions of boomers running laps around playgrounds and seeing who could throw a softball the farthest. Those good habits stuck with us.

But those extra eight years of life have come at a cost, helping to drive up health care expenses. Old people require a disproportionate amount of care, and medical costs have risen about twice as fast as inflation. Add it all up and health care was about 7 percent of gross domestic product in 1970. Now, it's 18 percent.

Human Rights & Inclusivity

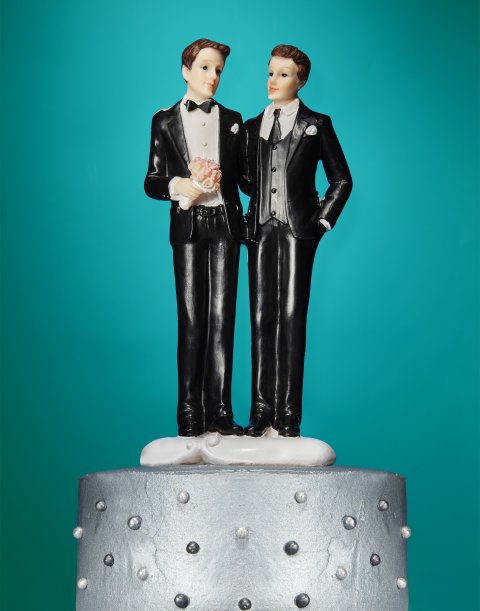

Not to put too fine a point on it, but in 1969 life for a gay, black, young woman (or any of the above) was pretty tough.

The baseline has moved so far, so fast that it's hard to explain what it was like in 1969, particularly outside major metropolitan areas and in the South. Until 1967, some states had laws that prohibited marriage between people of different races. Before enforcement of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, many towns had sundown laws where blacks were subject to arrest if they were out after dark. In 1981, a young black man was lynched in Mobile, Alabama, by the Ku Klux Klan. In 1969, women earned 59 cents on the dollar vs. men. Now it's 82 cents. Not great, but better. But before 1963, employers didn't even have to pretend to pay men and women equally for the same work. Until 1973, homosexuality was considered a mental disorder by the psychiatric profession. Before Roe v. Wade in 1973, abortion was a crime in many states.

We are far from living in a fair and equal world, but it is decidedly fairer and more equal than it was in 1969 and much of that is due to boomers. We voted. We marched—at our schools and in our hometowns, and after piling into beat-up old cars and driving through the night to Washington. We agitated and demonstrated. Sometimes we even rioted—as in Chicago in 1968 and New York City in 1969 (Stonewall). Sometimes we paid a heavy price—people went to jail, and at Kent State University in 1970, students were killed by the National Guard. Today, there is at least some measure of indignation when we see unfairness. And there is redress, both legally and in public shaming. We have not eliminated bias, but we have delegitimized it.

The Environment & Climate

Millennials face some very serious environmental issues—the two warmest years in history are 2016 and 2019; there are 330 billion pounds of plastic garbage floating in our oceans; and an estimated 200 species go extinct every single day. Very little is being done about it because of politics. But we had some pollution issues of our own. On June 22, 1969, the Cuyahoga River, a nasty, black, oozing, bubbly waterway that wound through Cleveland, caught on fire. Really on fire, with huge, billowing plumes of smoke. According to Smithsonian magazine, it had caught on fire a dozen times before. Air pollution caused by cars in American cities was so bad that pedestrians wore gas masks. Visibility would sometimes drop to two blocks. According to journalist Rian Dundon, they called L.A. (Los Angeles) "Smell-A." Tens of thousands of Americans died from pollution-related disorders. (Of course, it could have been worse. In five days in 1952, 4,000 people in London died from smog caused by coal used to heat homes.)

It was common for factories to simply dump waste onto the ground or into waterways. In 1953, Hooker Chemical sold the Love Canal, one of the most polluted sites in America, to the city of Niagara Falls. They built a school. In Athens, Georgia, barrels of radium waste from an old watch factory (it was used to make the watch hands and numerals glow in the dark) sat rusting in an unfenced yard behind the closed factory. Many of the women who'd worked there died from jaw cancer caused by licking their paint brushes to make the tips sharp. In all, 40,000 sites across America were identified as dumping grounds, 1,600 of which were considered priorities. And before 1972, the accepted way to get rid of the nuclear waste from power plants was to just take it out into the ocean and throw it over the side of the boat. In 1982, scientists found that huge holes were appearing in the ozone layer, the part of the atmosphere that protects us from solar radiation.

Today, people fish in the Cuyahoga River. L.A. still has air pollution, but it's about 40 percent of what it was, even though 3 million additional people live there. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), "Between 1970 and 2018, the combined emissions of six key [air] pollutants dropped by 74 percent, while the U.S. economy grew 275 percent." Even Mexico City has breathable air now. Many of the most polluted dump sites have been cleaned up, and there's no more ocean dumping of nuclear waste. In 2019, the "hole" in the ozone layer was the smallest ever measured. It's expected to close by 2075. It's considered one of the most successful environmental interventions in history.

It's taken a lot of work. The EPA's founding in 1970. 1972's Clean Water Act. The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter in 1972. 1980's Superfund law. 1987's Montreal Protocol (banning chlorofluorocarbons). New technologies making vehicles and industries more efficient and cleaner. Activist organizations like the Sierra Club, the Environmental Defense Fund and Greenpeace. New levels of public awareness, responsibility and commitment. Large-scale deployment of technologies like electric cars, home solar, solar power from photovoltaics and wind power, which now supplies around 7 percent of America's power. That sort of broad, sustained effort is what it takes to fix an environmental problem. It's now time to apply what we've learned over the past 50 years to plastics and global warming.

Culture

They call the 1950s the Golden Age of Television. Pish. This is the Golden Age of Television. And movies. And music. And books. And probably just about every other cultural vector you can think of. This is the Golden Age of Culture. Better creative output. Better performers. But you have all that because of us.

Before the 1970s, culture in the U.S. was tightly controlled and highly commercialized. The big music labels determined what you heard, the big publishers what you read, the big studios what you saw. The control was both informal and formal, from radio stations refusing to play "Negro" music and black artists to censorship of movies, albums and television programs. In 1952, the National Association of Broadcasters established the Television Code, which among other things prohibited profanity, sex, realistic violence, irreverence about God and religion, or the negative portrayal of law enforcement or family life.

We boomers don't like rules. Especially dumb ones. We broke down the soft barriers between genres, mixing rock and folk and blues and classical. We showed sex in movies—real sex, not just heavy breathing and passionate stares. And most of all, we refused to take anything as sacrosanct or untouchable. We created National Lampoon (1970) and Saturday Night Live in 1975. Hill Street Blues (1981) broke the police procedural mold with its intertwined storylines, multi-episode arcs and mix of personal and workplace stories—devices still used today. We poked and pushed at that censorship envelope until it finally broke. The Television Code ended in 1983, although music is still censored on TV and on the radio (the "radio edit" of CeeLo Green's song F**K You has the lyrics as "Forget You), along with movie content rating codes. Because of us and the abetting technologies of digitalization and the internet, we now have the most exciting and vibrant cultural environment ever.

It's worth noting that it's not just entertainment where we have more choice. In 1970, a typical grocery store had 6,000 items. Today, a regular grocery store has about 40,000 items, and a Walmart supercenter has 120,000. Amazon had over half a billion products for sale in 2017 and was adding a million products a day. In every category—electronics, airlines, hotels, clothes, furniture, you name it—the number of available items is growing at what feels like an exponential rate. All that choice can feel like a burden—until, of course, you don't have it.

Technology

Technology has exploded over the past 50 years, driven by boomers. Electronics. Pharmaceuticals. Digitalization. Materials. Nanotech. In 1969, around 72,000 patents were granted. In 2018, almost five times as many were approved, roughly one every 90 seconds, day and night, weekends and holidays. According to a brilliant 1997 essay by W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, a century ago major innovations like the car, electricity and the telephone took about 50 years to become mass market items. Midcentury, the time to reach the mass market had dropped to about 25 years—for example the radio, TV, VCR and microwave. The latest wave of innovations—the PC, cellphone, antidepressants and the internet—took 10 years or less. What that means is that we are the first generation with "unrecognizable" technology. That is, if we magically transported someone from 1919 to 1969, they'd recognize every single device in a home except for the microwave. But if we transported someone from 1969 to today, they wouldn't recognize half of our devices—laptop, Alexa, Kindle, the cat's laser pointer, DVD player, router, etc.

It's no small matter to handle that much innovation. We consumers have trouble keeping up—in little ways, like having to replace still-functioning devices, and in big ways, like falling behind in workplace skills. Business models become obsolete very quickly. In 1998, a Motorola-backed company called Iridium began launching satellites into space with the idea of providing a worldwide communication service for business people and travelers. Problem was, by the time it finished launching the 66 satellites three years later, cellular technology had gotten so good and was so widespread that it made Iridium obsolete.

We boomers were the ones who sped up technology, and we are the ones who slowed it down. We realized any technology powerful enough to save the world is powerful enough to destroy it. We questioned technology and pushed for things like natural and organic products, curbs on the use of X-rays and radiation, new regulations for chemical producers and chemicals, and a hiatus in new nuclear plant construction after the Three Mile Island disaster in 1979, in which a nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania partially melted down and leaked radiation.

Consumers in Europe and California are now moving to establish tighter rules around identity protection. And we are keeping a wary eye on AI and genetic modification. Sometimes our boomer techno-skepticism goes too far, as with the anti-vaxxing and anti-genetically-modified-organism movements. Still, it's reasonable to be at least somewhat paranoid. In 1938, X-ray machines were used to measure children's feet in shoe stores. Technology is wonderful but dangerous. It could've destroyed our world already in any number of ways—nuclear, chemical, genetic modifications. But it hasn't, because we haven't let it.

The Bigger World Outside America

There is a big world beyond the wall, and while much of it still lags behind the U.S. and Europe in terms of economic development and human rights, it's a lot better now than it was in 1969. The website Our World in Data has become the go-to resource for measuring global progress. It's showing improvement across almost all measures of human progress. Here are a handful of metrics, out of hundreds. In 1969, 449 people out of every 100,000 died from an infectious disease. Now, it's 140, a drop of 69 percent. Over the decade of the '60s, almost a million people died in wars. Over the most recent decade, it was around 567,000. That's twice as many people on earth and half as many deaths. But the real progress has been on poverty and hunger. In 1969, 36 percent of the world's population lived in what the United Nations terms "extreme poverty." Now it's 8 percent. On average, 4,600 people starved to death each day during the '60s. Now, it's one-fifth of that, despite a larger population.

And here's another way we're better off. In the '60s, the most common form of government on earth was dictatorships. There were 119 autocracies and only 36 democracies. Today, there are 99 democracies in the world. Yay freedom!

Of course, averages deceive. The fact that people, on average, are better off isn't very comforting to people in Syria, Central America or the South Sudan. Nor does this address the elephant in the room, climate change, which is likely to adversely affect developing nations far more than developed ones, which can just turn down the thermostat.

None of this is to say the world is as it should be. We said better, not perfect. There are new problems, like AI and the loss of privacy; old problems that we didn't solve completely, like environmental degradation; and old problems where we made progress but are now sliding backward, like civil rights, with over-incarceration and resegregation. As frustrating as those things are, we shouldn't lose sight of the progress that's been made. Generations solve the problems they are presented with. The generation before us took on autocracy and dictatorships. We took on social change. Your turn.

You are ready. You're bigger than we were, by about an inch; smarter, by about 10 IQ points; much better educated—far more people are completing high school and college than ever before. You have extraordinary technology. And though it's hard to quantify, you have another advantage we didn't—you're woke. We understood we needed to account for things like bias and privilege, but we didn't really know how. You have a much better understanding of the world around you and how it works.

Here's one last piece of advice. Aim higher. Your passion for change seems to be mostly for yourselves—health insurance, child care, student loans, paid family leave. Our passion was often to help others: civil rights, apartheid and famines in places like Bangladesh, Biafra and Ethiopia. Yes, it was naïve to think that a few concerts like Live Aid could save millions, but it was rooted in good intentions. Our generation may have failed in the execution, but we did not fail in ambition.

You're right to be scared by the enormity of the tasks before you. It could be very bad if you don't do something. But you will do something. And as you do, do your best to avoid our mistakes—but don't lose sight of what we did right. Good luck.

OK, millennial? OK.

→ Sam Hill is a Newsweek contributor, consultant and best-selling author. Thanks to the following for the statistics used, beyond those already cited: Statista, Census Bureau, NOAA, NBER, National Institute of Justice, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, CDC, National Committee on Pay Equity, U.N., professor Guido Alfani, the Sentencing Project, the Disaster Center, Timeline, Paycor, Leftronic, NomadWallet, 123 Test, Live Science and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Corrections 3/10/20, 3:28 p.m. E.T.: A previous version of the story compared median household income from 1969 with average HHI from 2019; the updated version uses median income to compare households in both periods. It also overstated the extent to which income per person is higher; it is 20 percent, not 50 percent. The word "billion" was also omitted from a comparison of car death rates; the updated version notes that one person died in a car accident for every 1 billion miles driven in 1969 (not every 1,000 miles) vs. one death per 3 billion miles driven in 2018 (not 3,000). We regret the errors.