Terry McAuliffe was the Governor of Virginia during a disastrous Unite the Right rally which took place on August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee—and the renaming of the park where it was located from Lee Park to Emancipation Park (it was since renamed again, to Market Street Park in July 2018).

The white supremacist and neo-Nazi protesters and the counterprotesters clashed violently as heavily armed right-wing militia loomed prominently over the proceedings. Governor McAuliffe called in the Virginia National Guard to end the rally even before its official noon start time.

Shortly thereafter, one of the neo-Nazis, James Alex Fields Jr., drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer, and injuring 35 others. Fields was recently sentenced on state charges to a second life sentence plus 419 years for his confessed crimes.

In a social media post she had written before her death, Heyer said, "If you're not outraged, you're not paying attention." Two Virginia State troopers and close McAuliffe family friends, Jay Cullen and Berke Bakes, also lost their lives when their police helicopter crashed outside of Charlottesville during their surveillance of the rally.

After the tragedy, McAuliffe was unequivocal: "I have a message to all the white supremacists and the Nazis who came in to Charlottesville today. Our message is plain and simple. Go home."

In this excerpt from his book, Beyond Charlottesville: Taking a Stand Against White Nationalism, McAuliffe describes the events of the morning of the Unite the Right rally and why he had to act quickly.

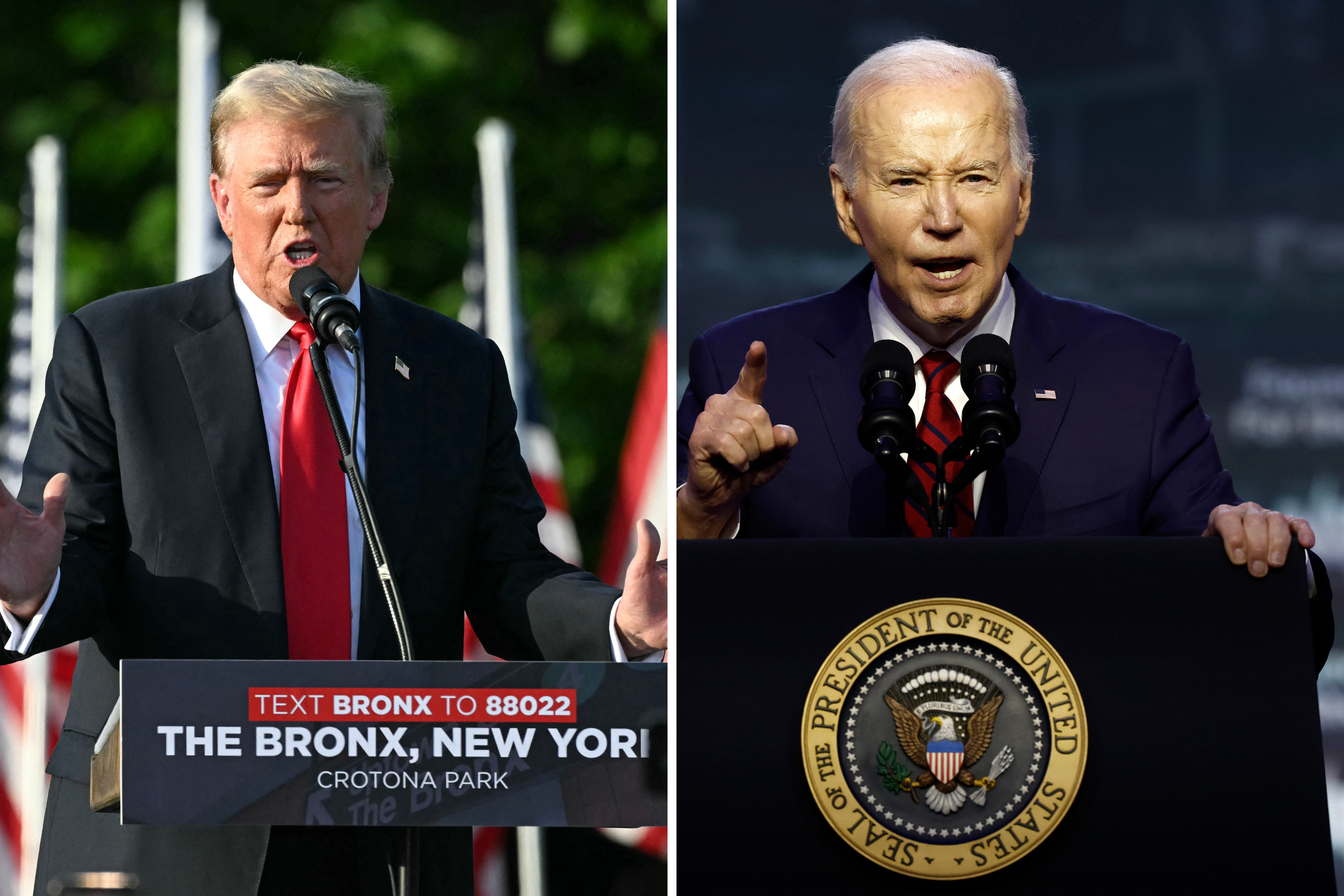

McAuliffe's book is disturbingly relevant given the recent tweets by President Donald Trump in which he told a group of progressive Democratic congresswomen of color—aka "The Squad"—to "go back" to their native countries. He was subsequently condemned by the House for "racist language." And a few days later, at a political rally in North Carolina, the frenzied crowd shouted "Send her back," referring to Representative Ilhan Omar.

We asked McAuliffe about the attacks on Omar and the Trump rally chants. His response: "He [Trump] is baiting us, and we should all stop talking about his racist taunts. Let's get back to healing and fixing our country."

We'd made all the preparations we could at the state level, and had full mobilization of our State Police and National Guard, but I remained apprehensive about what the day would bring. Brian Moran, the Virginia Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security, started calling and texting me with updates at 6:30 that morning. He and his deputy, Curtis Brown, attended a 7 a.m. briefing for law enforcement and first responders at the John Paul Jones Arena, where Department of Corrections buses were lined up to take our troopers to downtown Charlottesville.

"I let them know we had the potential for violence, that while precious few of us were from there or ever lived there, that Charlottesville was our city that day," Colonel Steven Flaherty said later.

Brian called the Charlottesville mayor at 7:15 a.m. to check in with him. We wanted to make sure the mayor was well aware that we were mobilized in force and ready to do anything we could in support. Next, Brian and Curtis, along with Colonel Flaherty, the superintendent of the Virginia State Police, drove over to a downtown garage. As they were pulling off the ramp onto the third level, they saw a group of heavily armed men in fatigues exiting their vehicles.

"They ain't ours?" Brian said to Curtis.

They both shook their heads and braced for the rest of the day. Brian was in place at the corner of Emancipation Park at 8:35 a.m. when he watched the first alt-right types arrive and assemble, some in helmets, carrying shields and flag poles. Jason Kessler's permit called for a rally between noon and 5 p.m., and the marchers were already massing this early in the morning.

Brian stood within a few feet to listen in on their chants and conversation to glean any information he could on how they were organizing. He tried to identify as many different militia insignia as he could. All around him the crowd of young white males grew. Soon they were lining both sides of the street.

Gay Lee Einstein, a pastor at nearby Scottsdale Presbyterian Church who lived in Charlottesville, was part of a gathering of hundreds of clergy heading

toward the rally that morning. She told me she'd found a plastic baggie full of rocks and a white piece of paper warning of "Shocking crime facts" and signed by the Ku Klux Klan, closing, "Wake up, white America!" She stayed with the group as long as she could. "I started crying during the thing," she told me.

Eileen, a registered nurse who was volunteering that day to help out as she could, was with the group of clergy near Emancipation Park that morning. "I was in the middle of all of it," she told me later. "We watched the crowd grow. I saw a lot of aggressive sexism toward young women. I saw a lot of women being called the C-word and being mistreated. One women was a little on the chubby side and these men were saying things like, 'You're a little fat, but we'd still do you.' I was so perplexed by it all, I went back and studied it. When hate wants to find something to hate, they just kind of change their target."

Around 10 a.m., I was keeping an eye on my phone, ready for the latest from Brian, and he sent me a picture of a heavily armed militia marching into the park in formation, like they owned the place. They were so loaded up, they looked like extras in a Rambo movie. It was a very disturbing picture. Brian gave me a full report on those militia men in camouflage gear with large semi-automatic weapons and extra ammo slung over their shoulders.

"Governor, these guys have better weapons than our State Police," Brian told me sarcastically.

"Who the hell are they?" I asked.

"I don't know," he said.

"Well, go find out," I told him.

So Brian walked over and tried to talk to these guys. I could hear most of what was said, since he was holding his phone and still had me on the line. The first militia member he approached was unresponsive, so Brian introduced himself as the secretary of public safety and tried another one. This time, the militia member was more talkative. He explained that his group was there to protect the First Amendment (and, obviously, the Second). It went so well, Brian decided to look for the leader of the group and try to negotiate a truce or at least understand what this militia saw as its role that day. The next member he approached refused to talk to him.

"I can't talk to you, sir," he said. "You have to talk to my CO, sir!"

So that was how it was going to be. For us it was one more element of insanity to have all these guys walking around in camouflage uniforms with revolvers strapped to their sides and huge semi-automatic weapons. It was surreal. We didn't know why they were there—and I'm not sure they did either.

It turned out this was one of many right-wing militia groups that showed up that day, including the Pennsylvania Light Foot Militia, the New York Light Foot Militia and the Virginia Minutemen Militia. They were well organized, well-armed—and intimidating—and said they were against both sides, neo-Nazis and counterprotesters. One of the militia leaders dismissed both sides as "jackasses."

Giddy with Pride

This was the largest white-nationalist gathering in the United States in decades, and the neo-Nazis and other fanatics were giddy. They were having the time of their lives. "The white nationalists were so young," Pastor Viktoria Parvin of St. Mark Lutheran Church in Charlottesville said later. "They were laughing, like they were going to a party."

Naturally, David Duke, the former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, was there. He grinned and beamed to well-wishers. "This represents a turning point for the people of this country," Duke said that morning. "We are determined to take our country back. We are going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump, and that's what we believed in. That's why we voted for Donald Trump, because he said he's going to take our country back."

READ MORE: Former Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe on Charlottesville, racism and Donald Trump

The crowd loved it. They were whipped up into a frenzied state. They yelled at an African American woman that they'd put her on the "first f— boat home" and telling any white person standing side by side with an African American they were going "straight to hell," finishing with a Nazi salute.

The words these marchers were spewing were unbelievable. Profane, disgusting, infuriating. It's worth remembering that nobody is born with the hatred that these people spewed. Nor were they representative of American values. We're a nation of 328 million people, so let's not lose sight of the fact that these were a thousand people marching, a small, fringe element pulled together from 35 different states. They came out of the woodwork. They came out of their cellars. This was going to be a great day for them. This event had been hyped so much, especially after the torchlight march the night before; everyone in the world knew about this rally.

There were so many different groups and uniforms, it was confusing. There were huge Confederate flags and huge red flags carrying the swastika of the Nazis. There were patches with swastikas and Confederate flags. At times, it was hard to tell whether the alt-right marchers were directing their hate more at black people or more at Jews. "As Jews prayed at a local synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel, men dressed in fatigues carrying semi-automatic rifles stood across the street, according to the temple's president," The Atlantic reported. "Nazi websites posted a call to burn their building. As a precautionary measure, congregants had removed their Torah scrolls and exited through the back of the building when they were done praying."

Hard to believe this was 2017, not 1937. I was very concerned about the weaponry Brian was observing out there. The marchers were carrying semi-automatic weapons, pistols, long guns—all legal under Virginia open-carry law. It's scary enough to see one man standing on a street corner with a long gun, but scary as hell when you put hundreds of men with semi-automatic weapons together in a small space. My biggest fear was that if some hothead started firing shots, all hell would break loose and we'd have dozens of body bags.

I was at home watching on cable television and they started showing a lot of fights. The world was convinced that pandemonium had taken over the streets of Charlottesville. It looked like the entire place was a melee. They kept replaying the same skirmishes over and over, and for a lot of people watching it looked worse than it actually was, but it was clearly a dangerous, volatile situation that could get out of hand in a hurry.

At 10:06 a.m., I called Colonel Flaherty to get his take.

"Governor, there's a lot of action downtown," he said. "I'm very concerned with the way things are going."

After dealing with Colonel Flaherty for three-and-a-half years, I knew what he was trying to tell me—things are about to blow.

I knew it was time to start thinking about declaring a state of emergency and dispersing the gathering, so at 10:21 a.m. I called AG Mark Herring; my counsel, Carlos Hopkins; and Lieutenant Governor Ralph Northam to put them on notice that I was preparing to declare a state of emergency.

As bad as the clips made it look, up until that point what we were seeing on the ground was more or less in line with what we'd expected. When you've got a thousand people gathered, carrying sticks, many of them spoiling for a fight, there are going to be incidents. There will be some pushing and shoving. There will be some skirmishes and fights. The reality was that this could swing either way.

Crowd Control

The key to controlling a protest is always keeping the different groups separated. That would have been a lot easier at McIntire Park, but because of the ACLU and one judge, this roiling mix of thousands of demonstrators and counterprotesters was all packed into a small area in and around Emancipation Park. (Charlottesville officials had tried unsuccessfully to move the rally to the larger McIntire Park on public safety grounds. But the demonstration reverted back to Emancipation Park when the ACLU sued on behalf of the Unite the Right rally organizers to keep the original venue—and won.)

The Charlottesville police's plan, unfortunately, relied at least in part on the honor system and the hope that the neo-Nazis would do what they'd said they would. It didn't work out that way. No surprise.

"Charlottesville Police Chief Al S. Thomas Jr. said the rally goers went back on a plan that would have kept them separated from the counterprotesters," The Washington Post reported. "Instead of coming in at one entrance, he said, they came in from all sides. Headlong into the counterprotesters. A few minutes before 11 a.m., a swelling group of white nationalists carrying large shields and long wooden clubs approached the park on Market Street. About two dozen counterprotesters formed a line across the street, blocking their path. With a roar, the marchers charged through the line, swinging sticks, punching and spraying chemicals."

Reporter A. C. Thompson was in the middle of the action. "We witnessed one instance where a battalion of white supremacists encountered an older group of counterprotesters," he said later. "They were like give-peace-a-chance, middle-aged, and senior-citizens kind of folks. And the white supremacists just absolutely pummeled them."

READ MORE: How Donald Trump decided to go soft on white supremacists

Our folks had reviewed a long list of contingency plans and underlined the importance of sealing off the streets around the park. That was basic crowd control, less a question of specific threat assessment, but that Saturday, the measures taken were inadequate. A single wooden sawhorse was all that stood in the way of cars driving down Fourth Street, a barrier that a Prius could plow through without much of an issue. At the corner of Market Street and Fourth Street NE, the way was blocked by a single officer stationed there.

It was all sliding toward pandemonium, as Brian Moran watched from the command center on the sixth floor of the Wells Fargo building, giving me constant updates. "That was when the crowd converged into chaos," Brian remembers. "The access to the park was all messed up. In addition to the incredible naïveté that they would even follow such a plan, there were way too many protesters to follow such instructions. The park fencing was just too small to accommodate the crowds of either supremacists or counterprotesters. The design was just flawed. It required the two groups to interact."

The main issue on declaring a state of emergency was one of protocol. The default is always for local decision-making. Normally, the city would be the one to declare an unlawful assembly, and that was what Colonel Flaherty was expecting. He saw it as the call of Charlottesville police chief, Al Thomas. Brian Moran was going out of his mind trying to sort it all out.

"I'm in this window on the sixth floor looking down at what was happening below, and the command center was on the other side of the building; they were overlooking the Mall, so they weren't even eyes-on," he says. "So I kept running from this window to the other end of the hall, grabbing Flaherty, and saying, 'What the hell! You've got to make the call that it's time for the governor to declare a state of emergency. This is crazy out there. It's gotten bad.' But he was waiting on Thomas to give him the signal, because the city wanted to issue their declaration first."

Flaherty was in a tough position, and everyone knew it. Law enforcement always wanted to follow chain of command, but Brian had seen enough.

"Steve, this can't go on any longer," he told Flaherty.

Send in the Guard

At just after 11:15 a.m. my phone rang.

"Governor, you've got to declare a state of emergency," Brian said. "This is out of control. I'm seeing bottles being thrown. They look like Molotov cocktails. We can't wait for Charlottesville. Screw protocol."

I didn't need to think about it at all—not for half a second. I'd seen enough. It was time for decisive action.

"That's it," I said. "Send 'em in! Send in the State Police. Send in the Guard. Clear the damn park."

The record reflects that at 11:28 a.m., via text message, I confirmed that I had authorized a state of emergency. Immediately after my action, at 11:29, the city declared it an unlawful assembly.

A BearCat armored vehicle was moved into position. The Virginia State Police tactical teams—everyone outfitted in riot gear—got on bullhorns and at 11:32 declared it an unlawful assembly and notified protesters that they were clearing the park. The event was canceled and everyone had 11 minutes to leave.

At 11:43, exactly 11 minutes after the announcement, Virginia State Police tactical teams moved into place and cleared the park. By noon, the Virginia National Guard had followed the tactical teams in and secured the park.

The rally ended just before it was officially scheduled to begin at noon. We'd made it through with some minor injuries and no property damage. There had been no looting and no windows smashed. We were relieved. There was nothing else for me to do at that point. It seemed to be over, we all thought and hoped—but that wasn't ultimately, to be the case.

Excerpt adapted from Beyond Charlottesville by Terry McAuliffe, published by Thomas Dunne Books.