Hanns Scharff was already a legend when Allied forces captured him at the end of World War II. A businessman conscripted into the Nazi war machine in 1939 and assigned to interrogate captured Allied pilots, Scharff quickly earned a reputation in the Luftwaffe for his uncanny ability to elicit valuable intelligence from his subjects—without laying a hand on them. "He could get a confession of infidelity from a nun," one of his former prisoners later quipped. Like Wernher von Braun, the Nazi rocket scientist who got a second chance with the Pentagon's ballistic missile program, Scharff had expertise that was recognized after the war's end by the U.S. Air Force, which in 1948 invited him to lecture on his techniques and adopted many of his methods for its interrogation school curriculum.

Scharff's ideas gained currency over the decades but never completely won over the front-line intelligence agencies, especially after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Panicking over the possibility of another devastating assault, the CIA in particular ignored the evidence produced by Scharff and other like-minded interrogation veterans and opted for what amounted to the movie version of questioning suspects: threats and torture.

"Important lessons learned about the usefulness of non-coercive, 'strategic interrogation' techniques," wrote one expert in a 2006 historical study of U.S. interrogation methods, "were forgotten."

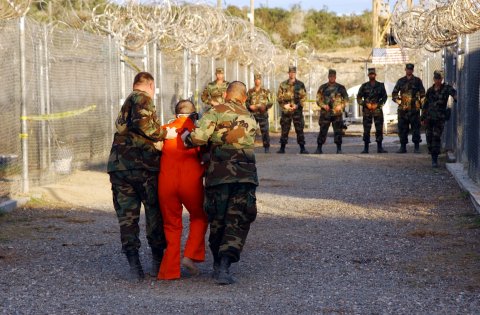

The eventual exposure of the CIA's black sites and euphemistically named "enhanced interrogation techniques," or EITs, triggered worldwide horror, condemnation and a Senate Intelligence Committee probe that found the techniques not only reprehensible but grossly overrated; victims would say anything to stop the pain, including false confessions that sent intelligence operatives around the world to nail down spurious leads. The study also charged CIA officials with exaggerating the program's accomplishments and downplaying its failures.

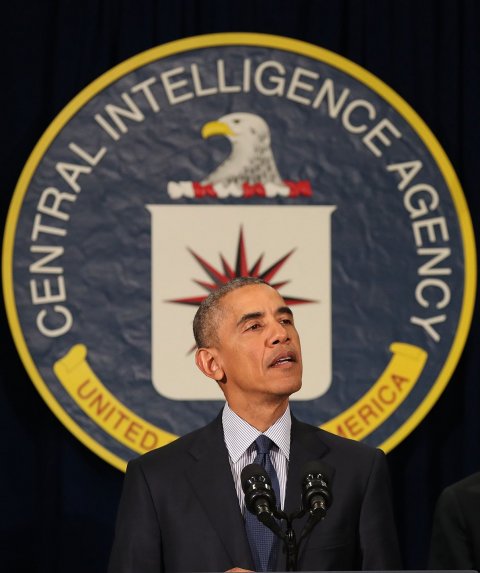

As one of his first acts as president, Barack Obama outlawed torture. Henceforth, the Army Field Manual on Intelligence Interrogation, or AFM, would serve as the bible for both CIA and military intelligence agencies. The era of torture seemed to be over. In 2009, the administration rolled out the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, or HIG, a combined FBI-CIA-Defense Department entity to get counterterrorism agencies on the same page for handling key captured Islamist militants.

But nearly a decade after the roughest stuff was banned, HIG experts tell Newsweek that interrogators still can't agree on a replacement for it. EITs have been outlawed, they say, but the AFM still relies on coercion rather than the kinder, gentler—and effective—methods that Scharff (and a lesser-known World War II Marine Corps interrogator of Japanese POWs, Sherwood Moran) used so effectively on their subjects.

Worse, they say, the Army and FBI have actively sought to block or water down reform efforts mandated by the legislation outlawing torture, the 2015 McCain-Feinstein amendment (named for the late Senator John McCain and Dianne Feinstein, the then–chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee the time). A number of psychologists, social scientists, interrogation experts and intelligence officials at an invitation-only HIG conference in Washington in October lamented that, while intimidation, manipulation and coercion were long ago judged to be counterproductive, the AFM continues to recommend them.

"A research study showing that practices under the Army Field Manual are not as effective as the Army would like people to believe...was suppressed, and the full study was not released by the FBI," Mark Fallon, a highly regarded former career agent for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and onetime chairman of the HIG's research committee, told Newsweek. The FBI declined comment.

Other knowledgeable sources said there were pockets of resistance to interrogation reforms in the Army. "I think there were parts of the Army that were very interested and supportive of the research that the HIG was doing, and then there were parts that were not," says Dr. Charles "Andy" Morgan, a forensic psychiatrist and former CIA senior medical intelligence officer who took part in the classified study. "I know there were turf wars. There were a lot of turf wars about that." Another scientist, granted anonymity to discuss private conversations with the Pentagon, said Army intelligence adopted "a very childish attitude" that "the HIG never seems to reach out to us for our opinions on anything, so why should we accept theirs?"

Not so, says Army spokeswoman Maria Njoku. "The Army will continue to work closely with the High-Value Interrogation Group," she told Newsweek in a statement. A U.S. official, demanding anonymity to discuss internal Army policy, added that "the HIG research validates what we were already doing."

In 2006, the Army did abandon some of its harshest interrogation methods, which had been authorized in a 177-page memo by Donald Rumsfeld, secretary of defense in the George W. Bush administration. But the retreat wasn't due to scientific research, says Morgan, who also helped draft a collection of papers that year by the now defunct Intelligence Science Board. The papers said there was little evidence to support the use of "coercive interrogation" methods.

"It moved because of public and social pressure," Morgan says, following media revelations of torture and humiliation of detainees at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq and the CIA's black sites. The Army's response, he says, was "Oh shit, we need to stop being the bad people in the news and change what we're doing"—at least for public consumption. The same impetus lay behind the creation of the HIG in 2009, he added. "The HIG was put together because of the CIA's bad rap. They said, 'OK, this is gonna be a three-group effort. You guys are gonna have to work together, and the CIA is not gonna interrogate people anymore. It's gonna be FBI interrogators and Army interrogators.' That's how all that first came about."

"I'm cynical," Morgan adds, "about science changing what they've done."

The CIA is out of the secret-sites interrogations business, current and former agency officials say. During her confirmation hearing, Director Gina Haspel pledged that waterboarding and other such measures would be prohibited under her watch. The HIG, led by the FBI, is now tasked with conducting high-level questioning of top-tier terrorist suspects.

But a big problem remained after prohibitions on torture, Morgan says. "There wasn't any guidance that said specifically, 'This is the way you have to interrogate people.'" Little is known about how combat units and special operations forces are conducting tactical field interrogations, say Morgan and other experts. Fallon recalls that "manuals and policies were in place, and ignored, when the Defense Department adopted EIT torture tactics in 2002."

Today, even with the EIT program outlawed, critics believe the "reformed" AFM leaves plenty of room for abuse. It advocates establishing complete, intimidating dominance over a captive. "This...over-physical, emotional, psychological control just has to be abandoned" as counterproductive, says retired Air Force Colonel Steven Kleinman, a former senior Defense Department interrogation official. Humiliation, he points out, stirs anger, resentment, resistance and a desire for retaliation—the very elements that drive someone into terrorism. "If humiliation would cause somebody to actually become a terrorist, why would they think humiliation would cause that terrorist to suddenly give up information?" he asks. "It doesn't even pass the logic test, let alone science." Studies show that extreme distress and physical pain also prompt subjects into false confessions.

But little definitive science is known beyond that. Even the rare, persuasive evidence like Scharff's remains highly anecdotal. When Jose Rodriguez, the CIA's head of clandestine operations, infamously ordered the destruction of the agency's black site torture tapes, valuable scientific evidence was lost, Morgan says. "We kept hoping they wouldn't destroy the videos, so that you could have a cleared scientist review it and say, 'Look...being really harsh to people gives you verifiable data [only] 10 percent of the time,' right?"

The AFM "absolutely needs to be revised from beginning to end, because none of their techniques have ever been assessed objectively for effectiveness," argues Kleinman, who helped expose interrogation abuses in Iraq. "They make these blanket statements [about the efficacy of their methods] without ever having to provide a shred of evidence to support them."

But it's hard to change attitudes reinforced by decades of TV cop shows and movies where threats, coercion and torture almost always work. In 24, the hugely popular early-2000s counterterrorism drama, hero Jack Bauer solved one ticking time bomb scenario after another by breaking a suspect's bones. (Oddly, Bauer never broke when a terrorist tortured him.)

Even some in the CIA workforce were seduced, Morgan recalls. "I was at the agency during the 24 [craze], and everybody thought, Oh, well, we should cut their heads off. We should threaten to cut their heads off. We should do anything Jack Bauer does. And you're, like, Oh dear God, this is silly." The agency ended up hiring two military psychologists, who had no experience conducting interrogations, to develop the EIT program.

Run under Rodriguez and his then–chief of staff Haspel, the program relied on beatings, sleep deprivation, deafening noise, prolonged isolation and, of course, repeated waterboarding to get subjects to talk. He remains proud of it, telling Newsweek that if the full Senate Intelligence Committee report on it were declassified, "the value of the program would be clear."

Kleinman dismisses the idea. "I would love to debate him in front of a neutral audience," he says.

Old prejudices and practices die hard. "When people go into law enforcement or intelligence, certainly in America, they know nothing about interrogation other than what they've seen on TV, which is completely fictional," Kleinman says. "But a lot of that is reinforced by people with 30 years in who've been doing it the same way. They've never reflected on their experience, they've never subjected their experiences to an objective analysis by third-party scientists."

Adds Susan Brandon, a research psychologist who, as the HIG's research program manager for eight years, was deeply involved in operations and training: "They perceive no need to change, because they have experience with it working." Rookie interrogators get guidance from superiors back at headquarters desks, says Morgan, who did a tour of duty in Afghanistan.

All of which may sound like a nerdy debate to people who believe in "hard measures," the title of Rodriguez's memoir (written with former CIA spokesman Bill Harlow)—people like President Donald Trump, who notoriously championed waterboarding "and worse" during his 2016 campaign. (He's been quiet on it since, possibly because, as the Lawfare blog speculated, he "may be heeding his lawyers' advice that, if such measures were ever legally defensible, they are less so now than ever before.")

Not that Trump cares much about legalities. During Thanksgiving week, he dismissed a CIA finding that pinned responsibility for the killing of exile-dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a U.S. resident, on Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman. "It's a shame," Trump said of the killing as he departed Washington for the holiday, "but it is what it is." He has likewise excused the murderous records of Russia's Vladimir Putin, China's Xi Jinping and the Philippines's Rodrigo Duterte.

Which makes reforms all that more urgent, says Fallon, who last year recounted interrogation abuses in his memoir, Unjustifiable Means: The Inside Story of How the CIA, Pentagon, and US Government Conspired to Torture. "We have to legitimize the manner in which we conduct investigative interviews," he says, "under a president that has claimed that torture works."

A radical change in public opinion may be necessary. A belated movie adaptation of a 1978 biography of Scharff, who pioneered soft talk and sold it to the Air Force, might be required. In 1992, Scharff died honorably in Los Angeles, after a hugely successful second career as a furniture designer and mosaic artist. One of his major works graces the Cinderella Castle at Disneyland.