The air-raid siren wails. Its shriek drowns out the screams on the street. You clutch your wife's hand and run to the shelter. This is not a drill. Your neighbors panic. The bombs are coming. The door to the shelter won't open. The bombs are coming, but the door won't open. This is not a drill.

A flash, so bright you see the bones of your hand, and a violent, invisible force that throws you to the ground. Darkness. A terrible heat follows. A hatch opens beside you. You fall in. You smell smoke and singed hair. Blind and burning, your last thoughts are of your wife: Did she hold our baby tight? Blackout.

Welcome to Fallout 4—one of the most highly anticipated video games of the past decade. This isn't Super Mario saving his princess or a massive Minecraft map or a cascading stack of crushable candy. It is a richly layered, deeply constructed open world full of dystopian science fiction. Set in a postapocalyptic wasteland outside Boston, Fallout 4 takes place 200 years after a nuclear holocaust. Players assume the role of survivors who return to the surface after getting frozen in a vault. They squint into the sun as the vault door creaks open, tasked to explore this bizarro world that's part Lost in Space and part Mad Max.

Related: APA Says Video Games Make You Violent, but Critics Cry Bias

The opening scene described above is just a taste of what Fallout 4's creator, Bethesda Game Studios, has spent seven years designing. Fallout 4 features 110,000 lines of spoken dialogue (the script of Apocalypse Now is about 7,500 lines). It's estimated that players will have 30 square miles to explore, including a faithful layout of what Boston, from Paul Revere Mall to Fenway Park, would look like if it survived a nuclear war. In the time it takes to fully explore Fallout 4, players could watch the Godfather trilogy straight through 40 times.

Fallout 's aesthetic cheekily evokes '50s-era sci-fi and the naïveté of early Cold War–era pop culture. The soundtrack, which will be available on vinyl, runs the gamut from malt shop hits to classical music to burn-in-the-fires-of-nuclear-hell gospel. Robots look more Ed Wood than Michael Bay, and in-game tutorials mimic the tone of those "Duck and Cover" safety films.

It's one of the most visually striking and narratively immersive games ever made. But despite its many artistic elements, some critics are hesitant to consider a video game, any game, a work of art. In 2005, film critic Roger Ebert wrote that "no one in or out of the field has ever been able to cite a game worthy of comparison with the great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers." Ebert argued that games are played while art is not, and that games are created to make money, not emotions.

The rebuttal to Ebert's argument comes, surprisingly, from Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. In 2011, he wrote the majority opinion for Brown v. EMA, a case about a California law that banned the sale of video games to minors. Video game fans latched onto the passage that read, "like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas—and even social messages—through many familiar literary devices…. That suffices to confer First Amendment protection."

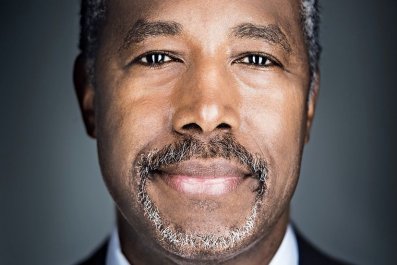

For Todd Howard, executive producer of Fallout 4 and the head of Bethesda Game Studios, there is only one reason some people wouldn't consider video games to be art. "They haven't played the right game yet," Howard tells Newsweek at the company's suburban Maryland studio. "What they probably don't know is that there are games for everybody."

Ebert eventually hedged a little. "It is quite possible a game could someday be great art," he wrote in 2010 in the self-effacing editorial "Okay, Kids, Play on My Lawn." Ebert's caveat was that no game had yet met the criteria for popular art.

Does Fallout 4 ? It is certainly popular. Poised to be one of the best-selling and most critically acclaimed video games of the decade, it's the biggest project to date for Bethesda. The game developer's 2011 fantasy epic The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim sold more than 18 million copies worldwide. Fallout 3 , released in 2008, has sold roughly 10 million. Both titles won game of the year at the Game Developers Choice Awards, an annual gathering of industry leaders, in addition to the dozens of awards the games received from industry press outlets such as IGN, PC Magazine and GameSpot.

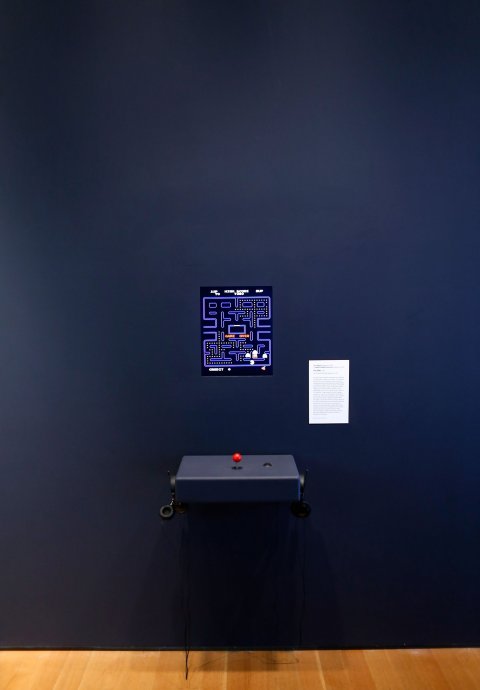

Chris Melissinos, curator for the Smithsonian American Art Museum exhibit "The Art of Video Games," says video games must be art because they are made of art. "Inside a game like Fallout 4, you can observe landscapes and sculpture and orchestration and narrative arcs and principles of design," he says. "All of these things that, on their own, we put on a pedestal or hang on a wall or write into a book to be published."

Howard explains how the team attempted to make Fallout 4 an immersive, artistic experience. "We look for elegance. Not simplicity," he says. "What we're trying to do is what we think is best about video games. We're going to put you in another world. Who would you be? What would you do?"

In Fallout 4, the players make ethical decisions and determine moral consequences—often within classic sci-fi scenarios. If a robot looks human, acts human and thinks it's human, should it be treated like a human? Do colonies of irradiated lepers deserve to live in isolation or does the threat of a pandemic justify genocide? These moments are full of what Scalia called "social messages" and are born of literary devices as old as Karel Capek's self-aware automatons in the play R.U.R., which premiered in 1921, or Mary Shelley's postapocalyptic plague survivor Lionel Verney from her 1826 novel The Last Man.

Related: The Future, as Told by 'Call of Duty: Black Ops 3'

"Fallout stands apart as an art form because not only is it narrative, not only is it artistically proficient, it is appropriating multiple areas of Americana and culture," Melissinos says. "It's directly based on your moral compass, how you view the world and how you want to see things unfold. And that's why it holds as art. And it holds as some of the most introspective and personal type of art that anybody can engage in."

Howard compares the experience of playing the game to watching a film. "In an open game like ours, the player becomes the director." And where critics like Ebert might argue that a scenario in which a creator gives up control of his or her work takes away its artistic merit, the concept of participants changing the outcome of an artistic work also encompasses elements of performance art and goes back to at least the 1960s, when Brazilian theater director Augusto Boal invited his audience to become "spect-actors." Boal's typical performances involved a scene in which a character was oppressed by an antagonist, and audience members were invited to pause the scene, replace the victim on stage and change the narrative in a way that resolved the conflict in the hero's favor. Sounds like a video game.

"Games can tap into that aspect that something live is happening," says Drew Davidson, the director of the Entertainment and Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University. "You have these wonderfully evocative experiences where you feel like your choices matter." Davidson says the ETC was born out of a partnership with Carnegie Mellon's performing arts program and that its founders—a mix of technologists and theater buffs—saw video games as an extension of performance art, since both contain elements like setting, narrative and voice acting.

Howard says video games also have a unique emotional advantage over other media. "There is the range of emotions lots of entertainment can give you, from fear to excitement to sadness," he says. "Games can do that. But the one emotion that only games can [create] is pride. Pride in what you accomplish."

Though naysayers will continue to naysay, at least for now, Fallout 4's creators believe that games will prove their artistic merit. "There's no question what we do is art. And it's an evolving art, as all art over the ages has been," says Istvan Pely, the game's art director. "It takes time to gain acceptance, but I think this will become the main medium for people to be entertained and to explore the human condition. Which is what art is all about—making people feel things and experience things."

Melissinos, who included Bethesda's Fallout 3 in the Smithsonian exhibit, agrees. "It's a variety of all the different art forms," he says. He adds, somewhat loftily, that games represent "the apex" of everything humans know about art at this point in the culture. "Video games are not only an art form; they are one of the most important art forms that have ever been at the disposal of mankind."

Unlike other art forms, though, video games are not built to last—technology fades at a much faster rate than plaster and ink. So while critics nitpick the lost meaning of a colored slab of dead wood, let's take time to engage the greatest entertainment technology of our era—regardless of whether it deserves space in a museum.