Thirty years ago, the music industry changed forever in the midst of the Parents Music Resource Center's fight to identify and label explicit lyrics.

The Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) formed in 1984 around the collective outrage of four women known for their ties to Washington political life. Founding members Susan Baker (wife of then-Treasury Secretary James Baker), Tipper Gore (wife of senator and future Vice President Al Gore), Pam Howar (wife of Realtor Raymond Howar) and Sally Nevius (wife of Washington City Council Chairman John Nevius) had become disturbed by Prince, Madonna and other music their kids were listening to. And on September 19, 1985, the culture wars came to a head in a "porn rock" Senate hearing featuring testimony from John Denver, Dee Snider and Frank Zappa.

From this political fervor emerged the "Parental Advisory" sticker that probably dots your CD collection today. In this oral history, Susan Baker, Dee Snider, Gail Zappa, Sis Levin and others tell the inside story of how it happened—and reflect on the 30 years that have gone by.

All of the material contained in this oral history was provided in the form of separate phone interviews with Newsweek, with three exceptions. Tipper Gore declined to be interviewed but did supply a statement through a representative. Cronos, of the metal band Venom, responded to interview questions via email. And the quotes attributed to the late Frank Zappa are from the artist's autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa Book. (The book was written in the late 1980s, hence the use of the present tense when referring to the then-active PMRC.)

Susan Baker, co-founder of the PMRC: It started because one day my 7-year-old came in and started quoting some of Madonna's lyrics to me, wanting to know what they meant. And I was shocked. I knew that you had to be concerned about movies and TV, but I didn't have a clue that my 7-year-old would be exposed to inappropriate songs.

Pam Howar, co-founder of the PMRC: I had a daughter. And anything delivered through music can be pretty powerful.

Susan Baker: It was "Like a Virgin." She [my daughter] said, "Mama, what's a virgin?" And I said, "What do you mean?" She said, "Well, Madonna sings this song: 'Like a virgin / Touched for the very first time.' What's a virgin?" I was speechless. Here she was still playing with dolls at 7.

Frank Zappa, musician and composer (in The Real Frank Zappa Book): There are several "historical accounts" from which to choose. Let's arbitrarily choose this one: One day in 1985, Tipper Gore, wife of the Democratic senator from Tennessee, bought her 8-year-old daughter a copy of the soundtrack album to Prince's Purple Rain—an R-rated film which had already generated considerable controversy for its sexual content. For some reason, however, she was shocked when their daughter pointed out a reference to masturbation in a song called "Darling Nikki." Tipper rounded up a bunch of her Washington housewife friends, most of whom happened to be married to influential members of the U.S. Senate, and founded the PMRC.

Sis Levin, executive director of the PMRC: I did a doctorate in conflict resolution in nonviolence. Which I teach at the university level all over the place. The fit is that the music is a form of violence in our children.… I took a desk and we had meetings and we talked about having opportunities to speak to the public. We would say, "Just listen to what they're listening to! And get a handle on it!" Because it does have an effect.

Susan Baker: We decided we would get together and get everybody on our address list and have a meeting and show them what we were upset about. Most of them didn't have a clue what was going on. That's how it started. We had no idea we were going to start an organization. We were just mad mamas who wanted our friends and, particularly, educators to know what kind of trash our children were buying. We felt we needed some information [in the form of] product labeling.

Kandie Stroud, journalist and PMRC spokeswoman who debated Frank Zappa on TV: We were a family completely saturated in music. I remember one time, one of my kids said, "Listen to this song, but don't listen to the lyrics, mom, you won't like them." Sure enough, it was some explicit song. I think it was something by Prince. I kind of looked into the topic and interviewed a bunch of different people in the music world. I thought, "Wow, it's really changed since the days of the Beatles and Elvis."

The PMRC set to work compiling contacts from their respective Christmas card lists and issuing press releases. The group sent a letter to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and more than 50 record labels. According to A History of Evil in Popular Culture, "The letter proposed that record companies either cease the production of music with violent and sexually charged lyrics or develop a motion picture-style ratings system for albums.… Violent lyrics would be marked with a 'V,' Satanic or anti-Christian occult content with an 'O,' and lyrics referencing drugs or alcohol with a 'D/A.'"

In 1985, the PMRC issued a list of 15 songs—nicknamed the "Filthy Fifteen"—which it deemed particularly objectionable and deserving of being banned from radio airplay. The Filthy Fifteen included songs by household-name pop stars like Madonna, Cyndi Lauper and—of course—Prince's "Darling Nikki." It also took aim at heavy metal, targeting lesser-known groups W.A.S.P., Venom and Mercyful Fate. The list included Twisted Sister's "We're Not Gonna Take It," which had become a hit single and video on MTV in 1984.

Susan Baker: Our goal in the beginning was just to alert people.… We just said, "Well, we'll start this group and see if we can get some labeling or some ratings. Kind of like movies." Within the first five or six months, we talked to Stan Gortikov, head of the RIAA. So we were working with him, and within a year they agreed that they would do something. One year afterward, they really weren't doing much of anything. When they were putting labels on things, they were real small and you couldn't read them. We had a big-time meeting with him. And by that time, we had a lot of publicity—in Newsweek and on the TV with Oprah and different things, Good Morning America. People were really getting riled up about it. Some legislators were even introducing bills to have in their state so they would have to have certain things on the labels.

Cerphe Colwell, longtime Washington, D.C., radio personality who testified at the PMRC hearing: Ironically, most of the heavy metal songs that they listed at the time were virtually unknown to the public. Heavy metal as a music format hadn't really blossomed. I truly believe to this day that one of the reasons that metal took off so much in the 1980s as a successful format is that the PMRC brought attention to what they thought was unacceptable, and of course that made it very much in the spotlight.

Cronos, singer for the Filthy Fifteen-targeted Venom: I was told about the PMRC during a recording session in the '80s, and I thought someone had hidden cameras, like pulling a prank on me to see my reaction, so I dismissed it as bollocks. Then, when I found out they were real, I couldn't understand how supposedly intelligent people could be so ignorant. Of course rock and roll has all of the subject matter they accused it of having. It's rock and roll! It's supposed to be hard-core and edgy. Most of us rockers have families, and we are responsible parents. We don't need the PMRC doing our jobs of protecting our kids from the harmful shit in this world. I would have been more upset if one of my songs or albums had not taken pride of place on their list.

Dee Snider, frontman for the Filthy Fifteen-targeted Twisted Sister: You talk about the music that was on the Filthy Fifteen, it's easy listening by today's standards. It's more than ironic that in the movie Rock of Ages, the Parents Music Resource Center-esque group headed by Catherine Zeta-Jones sang "We're Not Gonna Take It" at the rock star! That's irony in its purest form.

Susan Baker: We went all over the country talking to PTA groups and parent groups. And we'd say, "Look. This kind of inappropriate stuff is going to be out there in the culture. So you have to teach your kids to think critically about it."

Blackie Lawless, singer for the Filthy Fifteen-targeted W.A.S.P.: It's true, they made us a household word. But they made us a household word of people's grandmothers in the Midwest. Because the kids already knew who we were. The kids already had the records. Yeah, they make you a household word to somebody's grandma, but grandmas don't buy records. I think a lot of artists thought, OK, this exposure's gonna help us sell more records. But I don't think in reality it did. I know it didn't for us.

Joanne McDuffie, singer for the Filthy Fifteen-targeted Mary Jane Girls: I thought it was weird. It was like, "Really?"… When they picked that song ["In My House"], I remember being really, really irritated, because there was nothing in the song that would suggest anything inappropriate. Was the song about sex? Of course it was. But lyrically, it was very tastefully done. It wasn't something that would make your kids go, "Oooh, I'm gonna go figure out what she's talking about."

Blackie Lawless: I'm coming from a whole different perspective because I don't know if you're aware or not, but I'm a born-again Christian. I've not played that song ["Animal (Fuck Like a Beast)"] for almost 10 years. That song would not be something I would want to be represented as.

Joanne McDuffie: I think it was a blacklist. Or a modern-day witch hunt. Or an attempt at censorship for certain artists and certain songs. When I look at what happened, it didn't stop the airplay.… What it did stop was our consideration for the awards that I think any other artist of our stature or our popularity would have gotten.

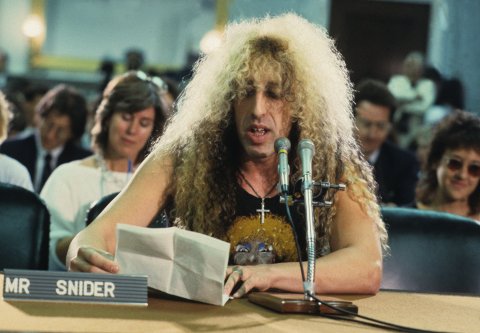

On September 19, 1985, the PMRC's efforts culminated in a much-publicized Senate hearing to consider the group's proposal. There, Tipper Gore advocated for "a warning label on music products inappropriate for younger children due to explicit sexual or violent lyrics." Alongside members of the PMRC, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation heard testimony from three popular musicians: Frank Zappa, Dee Snider and John Denver.

All three argued voraciously against what they characterized as censorship. In perhaps the most enduring testimony from the hearing, Zappa described the PMRC's proposal as "an ill-conceived piece of nonsense which fails to deliver any real benefits to children, infringes the civil liberties of people who are not children and promises to keep the courts busy for years."

Dee Snider: I just remember getting a call from my management office asking, "Would you testify at these hearings?" And I was like, "Hell, yeah." I assumed this would be, like, young people would rise up! And I was being asked to carry the flag. Didn't give it a second thought. "Yes, I will carry the flag into battle. Follow me!" As I stood out there by myself on the field of honor, I realized that nobody was following.

Susan Baker: Tipper and I were the ones that testified. It gave us more exposure, which we were hoping for. It was kind of a circus.… We were called awful things. They called us bored housewives and a bunch of crazy alcoholics. It was not a pleasant thing. But we said, "Well, so what? We think this is right." We just soldiered on. Like I said, the four founders really felt like we'd made progress and accomplished something.

Cerphe Colwell: I got a call from Frank Zappa and he said that he was testifying. Evidently somebody in his circle said that the PMRC, which was part of a Senate select subcommittee, was looking for some music experts. I was sort of a go-to guy. At that point I'd been on radio in D.C. for maybe 16, 17, 18 years. I played Frank's music and Frank had been a guest on my show many times. I jumped at the chance.

Larry Stein, attorney for Frank Zappa: [Zappa] was asked to, and he definitely wanted to because he felt very strongly about the issue. So we accepted the invitation for him to testify, prepared for it and went back there and testified. And my 15 minutes of fame is that when that MTV clip plays, he walks into the Senate and says, "Hi, my name is Frank Zappa and this is my lawyer, Larry Stein." The only picture of a client that I actually have in my office is the picture of Frank and me at the U.S. Senate.

Gail Zappa, Frank Zappa's widow: They were saying that they were going to have a hearing. And that pissed Frank off because it was a waste of resources and expenses to get involved in censorship of people's artwork, apart from everything else. He was pissed.

Dee Snider: The majority of fans just didn't get the significance of what was going on. "Now we know what records to buy!" That was the battle cry of the teens. "We know what records the cool records are!" Bullshit.

Larry Stein: It was fun getting Frank ready for his testimony. We believed that he would be taken much more seriously if he looked a little more businesslike. It was kind of fun if you see this picture of me and Frank together. This particular picture, his hair looks short, he's wearing a white shirt and a red tie and a dark suit. When people come into my office, I look like Don Johnson during the Miami Vice period. My tie is a little bit down, and I'm wearing a silver tie and people often come in and go, "Which one was the lawyer in that picture?" Frank knew what he had to do.

Dee Snider: I never met John [Denver].… I remember Frank and I standing back.… We were both not sure where John would be in this. We knew where he should be, as an artist—he should be on our side. But, again, he had crossed over, and he was literally that day coming back from NASA, where they were talking about him being the first musician in space.… So when he came out and spoke—and he spoke honestly about the way "Rocky Mountain High" had been protested and the movie Oh, God! had been protested and he stood against censorship of any kind—we were cheering in the back.

Frank Zappa (in The Real Frank Zappa Book): My only regret about that episode is that, under the rules of the hearing, I was not afforded an opportunity to respond when I was denounced by a semiapoplectic Slade Gorton (former Republican senator from Washington state) for my "constitutional ignorance." I would have liked to remind him that although I flunked just about everything else in high school, I did get an 'A' in Civics.

Slade Gorton (former senator from Washington): I didn't so much argue with [Zappa]. I told him what I thought of him and his language. You would have to look at the record of the hearings to get all of it. I just remember I attended the hearings. Senator Gore was a member of the committee. Frank Zappa was absolutely insulting and, I think, profane in his reference not only to their ideas but to them as individuals. The woman's husband didn't defend them. And I got very angry and did so.

Susan Baker: Some of [Zappa's testimony] was ludicrous. But John Denver was there, too. We understand how people feel. It's free speech! But we say, yes, speech is free. But when you buy a product in the store, it has a label on it that tells you what the ingredients are.

Slade Gorton: I have held Al Gore in utmost contempt ever since that day. He was on the committee and refused to defend his own wife.

Dee Snider: Gotta give John Denver [credit]. His testimony was one of the most scathing, because they fully expected—he was such a mom-American-pie-John-Denver-Christmas-special-fresh-scrubbed guy. Everyone expected that he would be on the side of right—right being censorship. When he brought up, "I liken this to the Nazi book burnings"—that's what he said in his testimony—you should've seen them start running for the hills! His testimony was the most powerful in many ways.

Dweezil Zappa: The whole experience of that was that we watched our dad go up against these people and just speak in a way that was great, because he went straight to the root of the problem. That's why it was great to hear him make remarks like that. He had one quote that was hilarious, where he said to the senators something to the effect of, "You are treating this problem like treating dandruff by decapitation."

The Senate hearings attracted a wealth of national media attention. In the aftermath, Frank Zappa appeared on TV several times, debating PMRC supporters. (Memorably, during a Crossfire appearance, he responded to a barb from Washington Times columnist John Lofton with: "How about you kiss my ass?") Zappa seemed to relish the opportunity to state his case while Snider resented that the politics overshadowed the music. Meanwhile, the PMRC succeeded in establishing the black-and-white Parental Advisory label, which began appearing on album covers at the discretion of individual labels. The PMRC gradually faded by the time Al Gore ran for president during the 1988 election.

Frank Zappa (in The Real Frank Zappa Book): A CNN show called Crossfire covered the PMRC topic twice with me as a guest, the first time in 1986 (when I told that guy from The Washington Times to kiss my ass), and then again in 1987, when George Michael's sex song was "controversial." Believe it or not, ladies and gentlemen, the premise of that second debate on Crossfire was (don't laugh) "Does Rock Music Cause AIDS?"

Kandie Stroud: I was asked by Charlie Rose to come on the show. If you want to call it a debate, call it a debate. He [Zappa] was not an ennobling human being. He made statements as far as I can remember like "This is about the First Amendment." It wasn't about the First Amendment. I'm a journalist, don't you think I support the First Amendment? It was about parental guidance [and] the music industry being responsible for what they poured into children's minds.

Dee Snider: It's a horrendous effect. Everything I feared and more. When I went to Washington, my concern was it wasn't about informing parents. It was that the sticker would be misused. The concern was that it would be used to segregate records. To keep creative artists' work from the general public. And true to form, stores wouldn't rack certain records.

Cerphe Colwell: Just as Frank had predicted, many stores, including Walmart, stopped carrying the dreaded, demonized records-carrying labels.

Gail Zappa: He did say that when these hearings were over, a lot of artists were going to get their contracts canceled. And, ironically, Frank was the first one that that happened to. Immediately after the hearing. They wanted his work to conform, and Frank provided a sticker that guaranteed that you wouldn't end up in hell if you listened to the lyrics. And they did not consider that sufficient. It was MCA that canceled his contract. They were offended by the language.… In 1987, Frank won a Grammy. In order for the committee to consider it—in order to be considered for a Grammy—record companies or artists submit copies of the record to various committees that would make determinations or vote on that particular record's eligibility. And so in the case of Jazz From Hell, they said, "Well, how come this doesn't have a sticker on it?" I said, "Why should it have a sticker?" "Well, shouldn't Frank's music be censored?" Well, really? Want to run that by me again? It turned out that nobody had listened to it. It's all instrumental.

Though the Parental Advisory labels are largely obsolete 30 years later, the question of the PMRC's lasting legacy remains. PMRC members interviewed for this article say they're proud of the work they accomplished. They feel they succeeded in promoting parental awareness of explicit lyrics; Susan Baker says it still gives her a smile when she sees a Parental Advisory sticker and knows she helped make that happen. But some of the artists targeted by the organization describe career downturns, label woes and—in some instances—death threats in the aftermath of the hearings. Prince and Madonna, meanwhile, are still playing "Darling Nikki" and "Like a Virgin" three decades later. Madonna performed "Virgin" Wednesday night at Madison Square Garden. Her latest album, Rebel Heart, comes sealed with a "Parental Advisory" sticker.

Tipper Gore, co-founder of the PMRC: In this era of social media and online access, it seems quaint to think that parents can have control over what their children see and hear. But I think this conversation between parents and kids is as relevant today as it was back in the '80s. Music is a universal language that crosses generations, race, religion, sex and more. Never has there been more need for communication and understanding on these issues as there is today. All of the artists and record companies who still use the advisory label should be applauded for helping parents and kids have these conversations about lyrics around their own values.

Susan Baker: [PMRC] stopped being operational about the mid-'90s. I moved and came back to Texas. We did what we felt we could do. We feel like we made a contribution.

Sis Levin: All I can say is, it was a group of courageous women who were willing to step out there and say, "This is bad, this is hurting our children, this is having an effect on not only the homes and the schools but the whole community. We need to take a serious look at this." That was pretty gutsy of them.

Joanne McDuffie: It kind of blacklisted me from certain areas of the business.… We didn't get the Grammys. We didn't get the American Music Awards, because of [the PMRC]. It cut me off at a certain point. I think that kind of stopped us before we got started. It stopped everything so that now there are only certain audiences who know about [our music]. Because it might have not played in certain areas or on certain radio stations. I think it hurt me.

Frank Zappa (in The Real Frank Zappa Book): If the scare tactics of groups like the PMRC and Back in Control have not made an impact on musicians, they have certainly made one on the executives of the record companies who can tell artists what the labels will or will not accept as suitable material under the artist's contract.

Blackie Lawless: I used to tell people that I felt like a brick wall, that nobody could knock me down. But it's very subtle the way it happens. A death threat here, somebody tampering with one of your vehicles there. It's not like someone tries to knock down your wall overnight. They take away one brick every day. And then pretty soon, you turn around and you look behind you [and] there's no more bricks in your wall. It ended up making me more of a recluse than anything.

Joanne McDuffie: Our song had the potential and was on its way to being No. 1. When they put that sticker on it, I think it maybe stopped at five. It definitely stopped us from going to No. 1.… I remember having an endorsement at the time from Ford Motors. But after this labeling thing, it disappeared.

Dweezil Zappa: Oddly enough, during the Clinton administration, we did have several occasions to spend some time with the Gores and actually became friends with them. It was never a battle of, "Oh, these people are terrible people."

Dee Snider: I feel a certain responsibility to carry the torch. It was certainly something that the Gores tried very hard to sweep under the carpet when he was running with Bill Clinton for the vice presidency.

Susan Baker: Tipper did not back away from the work that we'd done in the PMRC when Al was running for president, even though she got a lot of flack. Some of the people in his campaign seemed to walk back a little bit.

Joanne McDuffie: Let's go back to why they created this whole agency. It was for parents to control what your children were listening to. I was a parent at the time! That was my job. I was a single parent. I had a daughter and a son at the time. I'm gonna be mindful of what I'm singing because these kids are gonna grow up. I didn't want them to be ashamed of anything I was doing, nor did I want to be.

Dee Snider: Long-term, it was the first time people started to see me as having more to say than just a couple of catchy tunes. That I had a brain. A day doesn't go by that somebody doesn't walk up to me and say, "Thank you! For doing what you did."

Susan Baker: When we're traveling, sometimes somebody will come up to me when they find out who I am and they say, "We really thank you for doing that. Thank you for making us more aware."

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more