You know technology pessimism is getting serious when career technologists go rogue.

At an outdoor café on a sunny day in New York City, I sat across the table from Kentaro Toyama, who used to explore computer vision for Microsoft Research and co-founded Microsoft's lab in India. He quit those jobs and just published a book, Geek Heresy, that says technology is making social ills worse and won't cure any of our problems. A defection like that is as shocking as if a cat published a book called Why Dogs Are Better.

I asked Toyama why he and so many others in tech are turning to a dim point of view. Martin Ford, a Silicon Valley software guy, recently published the bleak Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. Even Bill Gates, who's as responsible as anyone for putting computers into our homes, now says artificial intelligence is dangerous and could doom humanity. And Stephen Hawking agrees! Stephen effing Hawking! Advances in robotics and AI are ginning up more paranoia about any technology since the atom bomb. Heck, the new Terminator movie is out, and audiences are starting to wonder if it's science fiction or a documentary.

"I think the pessimists are right about AI," Toyama replied, deadpan, while finishing his pastry. "And in fact it's going to be even worse."

Oy.

Whether he's right or wrong, the technology industry is getting an image it's not used to. While there always have been and always will be those who fear technology and change—many of them residents of France—most of the time technology has inspired optimism about the future.

Look at history. In 1851, the Great Exhibition in London set imaginations afire by introducing the masses to the wonders of steel, photography and the telegraph. The New York World's Fairs of 1939 and 1964 celebrated automation, cars, flight and a more prosperous future. The dot-com boom and globalization in the late 1990s set off visions of connectedness, peace and a new digital economy that would upend everything we secretly hated about the old economy—you know, like stores and travel agents.

New technologies represented hope, not depredation. They got people excited. Science and technology have generally enjoyed good PR for about two centuries. The tech industry rarely has had to worry about getting labeled as the bad guys.

The mood changed within the past year or so. The economy has been making people feel, for the first time, that AI is hurting them. Despite the low unemployment rate, long-term unemployment is troublesome, wages are hardly growing and the gap between the rich and everyone else is widening. As depicted in Ford's book and, earlier, Race Against the Machine by MIT's Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, AI is already automating knowledge work the way assembly lines once automated handiwork. AI software can now write news stories, concoct recipes, drive a car and decide who should get a loan. As AI automates brain work, fewer people—i.e., those who own and operate the software—make lots of money and do much more with far fewer employees. Tech investment firm Andreessen Horowitz operates under the banner "Software is eating the world." Increasing numbers of people fear that software is eating their livelihoods.

From there, a robot takeover suddenly looks possible if not inevitable. We all know technology only gets better, faster and cheaper. It's becoming easier to believe that computers running AI software will eventually become smarter than the smartest humans. Will they take all our jobs? Will they want the best seats in restaurants? Will they consider us a needless burden? AI can seem like it leads to a world that's lovely for machines and disastrous for us.

And now our ultraconnectedness seems like a looming problem too. With smartphones in our pockets—and there are today about as many cellphones as people in the world—we can have access to anything or anyone. Cities are becoming "connected" and "smart"—digital hives that better manage traffic, crime and development. Yet it's becoming apparent that hackers pose a sobering threat to an ultraconnected world. The Chinese got into the White House, and North Koreans got into Sony. CNN does stories about how a hacker could take control of an airliner through its Wi-Fi, and some experts are raising concerns that a smart city could be breached, creating chaos at paragons of connectedness like Singapore, San Francisco or Barcelona, Spain. We got a taste of our vulnerability on July 8, when technical glitches shut down United Airlines, The Wall Street Journal website and the New York Stock Exchange.

Last month, Pope Francis barged into the conversation. "People no longer seem to believe in a happy future," he wrote in his much-publicized encyclical. "They no longer have blind trust in a better tomorrow based on the present state of the world and our technical abilities. There is a growing awareness that scientific and technological progress cannot be equated with the progress of humanity and history."

When the pope turns on you, you've got an image problem. Look what happened to the communists after John Paul went after them.

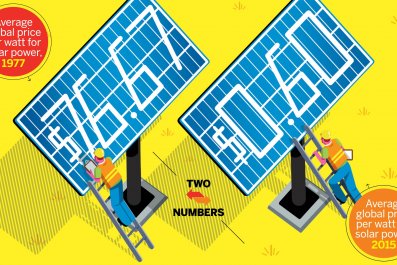

The doomsayers may be horrendously wrong. In fact, improving and deploying AI, software and other technologies like genetically modified crops seem to be the only ways this planet can support the population of 8 billion predicted for 2025. Plenty of evidence suggests technology is improving quality of life even while it suppresses middle-class earnings. Just think of all the free stuff you can do on a smartphone that would've cost plenty a decade ago. Software lets each of us—not just the plutocrats—do more with less.

Yet it's the perception that matters, and the tech industry needs to wake up to the whiff of a growing wildfire. Tech is used to wearing the white hat. The industry needs to think about how it would feel to have the PR of Big Oil. Not that bad publicity has made much of anybody stop driving cars and buying plastic, but the oil industry long ago got labeled as ruthless despoilers of our planet. Movie scripts make oil barons into villains. Reputations like that have an impact on who wants to work for you, how governments treat you and what parties you get invited to.

The tech industry needs to figure out how to again tell a story of optimism before no one wants to hear it anymore.