We climb eight flights of stairs. Eight more remain. This is sturdy Soviet concrete, dusty as death, but solid. So I hope, anyway. My guide, Katya, who is in her early 20s, has informed me that the administrators of the Exclusion Zone that encompasses Chernobyl do not want tourists entering the buildings of Pripyat for what appears to be an unimpeachable reason: Some of them could collapse.

But the roof of this apartment building on the edge of Pripyat, the city where Chernobyl's employees lived until the spring of 1986, will provide what Katya says is the best panorama of this Ukrainian Pompeii and the infamous nuclear power plant, 1.9 miles away, that 28 years ago this week rendered the surrounding landscape uninhabitable for at least the next 20,000 years. So we climb on, higher into the honey-colored vernal light, even as it occurs to me that Katya is not a structural engineer. And that the adjective Soviet is essentially synonymous with collapse.

And what do I know? Nothing. I am just a curious ethnic hyphenate, Russian-born and largely American-raised. In 1986 we lived in Leningrad, about 700 miles north of the radioactive sore that burst on what should have been an ordinary spring night less than a week before the annual May Day celebration. Considering that Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev wasn't told for many hours what, exactly, had transpired at Chernobyl ("Not a word about an explosion," he said later), you can safely extrapolate to what the Soviet populace learned on April 26: absolutely nothing. But a couple of days after the disaster, a family friend from Kiev called and said we had better cancel our planned vacation in the Ukrainian countryside.

Then details started falling into place, as workers at a Swedish nuclear power plant detected radiation, eventually determining that it came from the Soviet Union. That forced the ever-defensive Kremlin's hand, which admitted on April 28 that an accident had happened at Chernobyl. "A government commission has been set up," a statement from Moscow assured. My father, a nervous physicist himself, was not mollified. I remember, as clearly as I remember anything of my Soviet youth, his telling me to stay out of the rain.

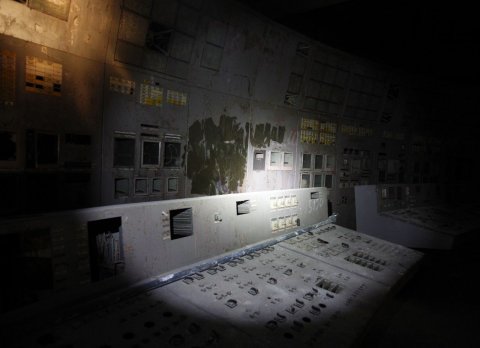

The narrative of Chernobyl has been told so many times, there is no point in regurgitating all of it here. Very briefly: a shoddy Soviet reactor, moderated by graphite instead of water; a turbine generator coastdown test that senselessly called for the disabling of all emergency systems; the reactor's fall into an "iodine valley" and the consequent poisoning of the reactor by xenon-135; the incompetence and impatience of the plant's managers, especially of Anatoly Dyatlov, a supervising engineer who stubbornly drove the test forward and would later serve prison time for his role in the night's events; the indefensible lifting of all but six of the 211 control rods; the reactor going prompt supercritical; the inability to fully reinsert the control rods, leading to steam explosions and graphite fires; a biblical pillar of radioactive flame surging into the sky.

Through it all, two off-the-clock workers fished in a nearby coolant pond. They continued to fish until the morning, receiving enormous doses of radiation yet somehow surviving. Theirs may be the only feel-good story of the night.

The toxic cloud that enveloped much of Europe that spring has intrigued me ever since. I can name all of the radionuclides it contained: cesium-137, iodine-131, zirconium-95 strontium-90, ruthenium-103.... But I longed to know its origins, the way a naturalist might yearn to see the source of a river somewhere high in the mountains, simply to fulfill the human need to discover beginnings and pay homage to them.

I also happen to be a journalist and now find myself in Ukraine when it is at the center of world events, as opposed to the periphery where most former Soviet states languish (when was the last time CNN did a gripping live remote from Uzbekistan?). Except I am about 90 miles north of Kiev, the site of the Maidan uprising, the epicenter of a conflict that has Russian President Vladimir Putin sharpening his swords again. Everyone else is reporting on Crimea, possible NATO retributions, a new Cold War...and here I am, in the midst of this "weirdish wild space" (h/t Dr. Seuss).

Katya is right. Not only do the stairs hold, but the view from the roof, 16 floors above Pripyat, is spectacular. Winter singes the air; nothing yet blooms. There is a severe beauty that is particularly Slavic, the earth at once fecund and stark. The white quadrangles of Pripyat seem to have risen up between the trees that grow thickly right up into Belarus, encompassing a forbidden zone of a thousand square miles. The V.I. Lenin Chernobyl Atomic Energy Station (the official name of what the world knows as Chernobyl) is visible in the distance as a squat collection of shapes, emitting equal parts radioactivity and mystery.

That apartment building was part of my two-day excursion into Chernobyl, one that quickly dispelled any notions that this swath of Eastern Europe is a radioactive wasteland. Or, rather, only a radioactive wasteland. I can't quite believe that I am saying this, but tourism to Chernobyl is booming. There were 870 visitors in 2004, two years after the Ukrainian government allowed (some) access to the Exclusion Zone. Today, the Kiev-based tour company SoloEast says it takes 12,000 tourists to Chernobyl a year, which accounts for 70 percent of the pleasure-visitors heading there (including myself). I even stayed at a luxury hotel of sorts, a neo-rustic cottage that featured towel warmers and a sign that said, "Please keep your radioactive shoes outside."

For the most part, the defunct station of reactors (the first went live in 1977; the last, the one that blew, in 1983) looks like a tidy industrial park in central Ohio: shorn green lawns, a smattering of abstract art, half-empty parking lots, a canal rife with fish. Nothing indicates that this is the site of the worst nuclear disaster in human history.

Yet as tourists Instagram away at Pripyat's ruins, Chernobyl is undergoing one of the most challenging engineering feats in the world, as a French consortium called Novarka tries to replace the aging sarcophagus that contains the reactor, a concrete shell hastily and heroically built in the direct aftermath of the meltdown. The place remains a half-opened tinderbox of potential nuclear horrors, and just because much of the world has forgotten about Chernobyl doesn't mean catastrophe won't visit here again.

But don't let that detract from your sightseeing.

WORTHY OF WORDSWORTH

Of the many atrocities committed against this swath of north-central Ukrainian soil, the most recent may be the American horror movie Chernobyl Diaries (2012), which meticulously sticks to every outworn convention of the horror genre, as if deviating from such would be a terror of its own. The poor viewer is presented with a group of happy-go-lucky young travelers, mostly American, respectively buxom and bro-ish; a goonish Ukrainian tour guide with the locution of a Neanderthal; and a Pripyat rendered in such an unrelentingly grim color palette that I thought the director (one Bradley Parker) may have smeared dirt and moss over his camera lenses.

The characters, wishing to "see some cool s**t," embark on a tour of Pripyat. All fine so far, just a little atmospheric unease. As night falls and the familiar, beery comforts of Kiev beckon, their van (surprise!) refuses to start. There follow many expressions of misplaced machismo, terror/wonder and good old animal fear, expressed in the purest clichés imaginable:

"We paid for this tour, bro."

"This looks pretty f**king sketchy."

And, inevitably, "Oh, s**t."

At one point, a character asks the question that is central to all hackneyed horror movies: "Are you sure we are out here alone?" You can figure out what happens from there. In any case, I certainly can't tell you, as I stopped watching about three quarters of the way through, having completed what I felt were my journalistic duties and not wishing to subject myself to this cinematic torture any longer. I do remember a pack of feral hamsters. Or something.

Katya, my tour guide, told me that American visitors are afraid of mutants lurking in the tenebrous alleys and dilapidated buildings of Pripyat. She finds this misguided concern easier to manage, however, than the fearless attitude of Polish and Russian visitors, who she says will climb into and over everything without any of the corporeal concerns one might harbor when exploring an abandoned, radioactive metropolis.

Igor, our driver, a Baptist with a Hebraically world-weary sense of humor, found it especially amusing that one American visitor thought that a covered walkway between two buildings was an elevated subway. Igor made several comments about the general naivete of Americans, perhaps suspecting that I enjoyed them. Most of the time, he simply remained in the car sleeping or listening to religious radio, including at one point a lengthy sermon on marriage that he did not turn down for my benefit. He has been to Chernobyl 500 times, and it bores him, he says.

Pripyat did not bore me. It is often called a ghost city, because after the Chernobyl explosion-though not immediately after it, tragically-the majority of the 49,000 residents of this town, 17,000 of whom were children, were ordered onto 1,216 buses and 300 trucks that had come from Kiev, without the basic explanation any neophyte emergency-management student would know to provide.

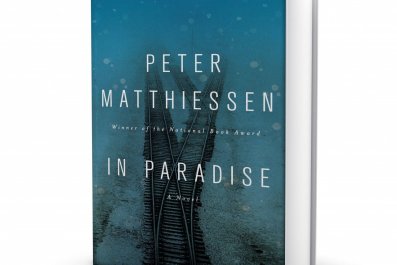

Of the many books written about Chernobyl, the only one I can confidently say you have to read is Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. It is the ordinary voices that make this book extraordinary. For example, this is how Lyudmilla Ignatenko describes the evacuation from Pripyat:

It's night. On one side of the street there are buses, hundreds of buses, they're already preparing the town for evacuation, and on the other side, hundreds of fire trucks. They came from all over.... Over the radio they tell us they might evacuate the city for three to five days, take your warm clothes with you, you'll be living in the forest. In tents. People were even glad-a camping trip!

Ignatenko's husband, Vasily, was one of the firemen sent immediately after the explosions right into the reactor's maw, where the radiation was far above the lethal dose. More than 20 would die from the exposure. In Voices From Chernobyl, she recalls someone telling her, as she watches Vasily expire in a Moscow hospital, that "this is not your husband anymore, not a beloved person, but a radioactive object with a strong density of poisoning."

Pripyat is less a ghost town than a museum in handsome disarray. An excellent museum all the same, surely the most authentic record of the Soviet debacle that remains (other than Russia itself). A pretty good one of nuclear energy, too. I have been back to my native Leningrad twice. I have stood in front of the plain cinderblock building where I was raised; have squeezed into a desk in the very same classroom where I was once a Pioneer and where, as I bathed in nostalgia, bored post-Soviet teenagers texted away; have posed humorously in front of the Lenin statue at Finland Station with the native Californian who would become my wife. And these were all fine pricks of memory. Pripyat, though, was a hammer. With sickle.

Not to get all William Wordsworth-at-Tintern-Abbey on you, but there was immense power in walking through a graveyard of gas masks on a classroom floor, or the fresh-meat station of what had once been a bustling supermarket, or the natal unit of a hospital, rusted cribs still looking, after all these years, as if they had just been robbed of their newborn contents. I don't want to claim to have heard the same "still, sad music of humanity" that famously played to Wordsworth on the banks of the River Wye, but, well, Pripyat is the most life-affirming place that I have ever been to, despite all the suffering that lingers there. For all the cancers, deaths, irradiations and lives broken, the place remains, and there is something to be said for brute rage-against-the-dying-of-the-light survival.

Pripyat is not receding in my mind, the way so many great museums have. Sometimes, what the soul needs is not a masterpiece. And so dusty Pripyat seems to have lodged, like a radioactive particle, into some deep neural fold: slippers on a hospital floor, a rusted circuit box, a piano that can still manage a plangent note or two. Outside the music school, a colorful chaos of mosaic tiles littered the pavement. Katya leaned down, then hesitated. "I would give you some to take, but you have a daughter."

We carried a dosimeter with us at all times; Igor, my driver, also had a beta ray detector in his car, which looked like an ancient remote control and remained largely inert. The dosimeter, meanwhile, would make its anxious clicks, but other than in a hot zone in front of a kindergarten, it rarely exceeded 3 or 4 microsieverts per hour-it read 3.88 µSv/h several hundred feet from the ruined reactor. That's less than what you get bombarded with on a round-trip flight between San Francisco and Paris (6.4 µSv/h). Igor especially delighted in pointing out this fact; he shares that proclivity with a great number of individuals on the Internet, where numerous websites are devoted to gleefully chronicling the radioactivity of bananas (pretty high; it's the potassium), Brazil nuts (the most radioactive food on Earth) and simply having a loved one sleep next to you (.05 microsieverts per night). I assault you with all these facts, in the manner of my Chernobyl guides, to simply point out that we are no more screwed in Pripyat than we are in Monterey or Omaha or Manhattan.

After our forays into Pripyat and the power plant, we would leave the Exclusion Zone, which one is allowed to do only after passing several dosimeter checks, conducted via ancient-looking olive machines that appeared (to my admittedly inexpert eye) to be as effective at detecting radiation as Mr. Magoo is at driving. Anyway, I passed. There was also a lot of handing over of paperwork to surly Ukrainian guards, who would probably rather be battling Russian invaders than inspecting the passports of American journalists. After several needlessly tense moments, the guards would allow us to pass, and Igor would speed down the empty roads of northern Ukraine, often while furiously texting. He did not wear a seat belt, and neither did I. It would have been a grave insult to do so.

Until very recently, the only places to stay while visiting Chernobyl were two small motels in the Exclusion Zone, which would have been reason enough not to come, at least for a spoiled American used to Western comforts (i.e., me). One tour company, in a heartwarming but ominous display of honesty, describes one of these motels, unimaginatively named "Pripyat," to be "Soviet-style simplistic," which is probably the worst hospitality-industry endorsement imaginable.

This yuppie reporter's savior proved to be Countryside Cottages, a pleasantly rustic cabin-cum-hotel set on a bucolic and fenced-in landscape in the village of Orane, on the banks of the Teteriv River. The cottage is outside the Exclusion Zone, with its strange currents of tranquillity and unease: You can walk about the village freely without having to undergo dosimetry checks. By my count, Countryside Cottages, which has now been open for about two years, is the closest-and only-good place to stay near Chernobyl. The best adjective to describe it is Western, and if you have ever traveled beyond the West, you will know what I mean. Yes, the electricity did go out one evening, but only briefly, certainly not long enough to steal the chill from the horseradish vodka in the fridge. There was also a fancy coffee machine, though, alas, no organic milk. SoloEast, which owns Countryside Cottages, boasts on its web page for the hotel, "We can also teach you to plant or dig potato." This agricultural instruction was neither offered nor, I can assure you, requested. I have already praised the towel warmers.

At the behest of my driver, Igor, I did purchase the Slavic trinity of smoked meat, alcohol and bread before leaving Kiev. In the evening, I would sit with these, watching the swift and surly Teteriv, listening to the incessant crowing of roosters. For all the discordances of modern travel, from a McDonald's in the Latin Quarter to "eco resorts" in Haiti, perhaps nothing is quite as surreal as the cozy country comforts of the Countryside Cottages, where you are supposed to forget, as you watch gaudy Russian cable on a flat-screen, the residual wreckage you have come to see.

FOR THE LOVE OF RUINS

Ruin porn is a thing. Trust me. It has made Detroit a destination, as there are apparently legions of tourists who'd rather behold the shell of the Michigan Central Station than guzzle piña coladas at a Sandals resort. The popularity of ruin porn is responsible for listicles like "The 38 Most Haunting Abandoned Places on Earth." Pripyat is first on this list, which also includes the creepy dagger blade of the Ryugyong Hotel in Pyongyang, North Korea, and Bannerman Castle in the Hudson River Valley.

While I was in Pripyat, the Tate Britain in London was staging a show called Ruin Lust, whose catalog includes a quote from the 18th century French philosopher and encyclopedist Denis Diderot: "The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures."

Ruin porn has even been the subject of an entire book: Andrew Blackwell's Visit Sunny Chernobyl: And Other Adventures in the World's Most Polluted Places (2012). The thing is amusing but ultimately too ironic and glib, though Blackwell does get credit for visiting, and dutifully chronicling his exploits at, the Canadian oil sands of Alberta; the refineries of Port Arthur, Texas; and the sewage canals of India. His section on Chernobyl promises to reveal "one weird old tip for repelling gamma rays."

For some, though, ruin porn is exploitative, a version of poverty tourism: gang tours of Los Angeles, jaunts through Soweto, that sort of thing. On the topic of her city having become a hot spot for urban explorers and gonzo pornographers, one Detroit cultural official has complained that "people here are very sensitive to treating Detroit like it's a big cemetery and our ruins are beautiful headstones. Those of us who live here don't like to be seen that way."

There is nobody in Pripyat to object to your voracious voyeurism. There are, however, some samosels in the Exclusion Zone, elderly settlers who returned to live on the land they had known and worked for decades. There had been about 180 villages here, and some people had survived both Stalin and Hitler. Rogue neutrons weren't going to keep them away. So they came back, illegally. Nobody bothered to expel them.

Visiting the samosels was uncomfortable in precisely the way that detractors of ruin porn suggest. It was like touring a decrepit zoo where the animals are in obvious distress. I met two villagers, Ded Ivan and Babushka Maria, in front of a homestead in the village of Paryshiv. Many of the surrounding buildings seemed to be little more than wooden slats that accidentally, and only occasionally, formed right angles. Both Ivan and Maria were born in the 1930s, a decade that began with widespread starvation brought upon Ukraine by Stalin. The following decade commenced just as grimly, with the invasion of the Wehrmacht: Ivan remembers being bitten by a German dog that jumped out of a tank.

You are supposed to bring the samosels gifts when you visit on tours such as the one I was taking, but we had forgotten this detail, so I simply handed Maria 200 hrivny ($16.913, as of this writing), which she placed into the pocket of a filthy light blue coat. Ivan was trying to fix a chainsaw, and my driver Igor helped. Meanwhile, Maria brought me over to see the couple's pig, and I was coaxed into feeding the snarling, smelly animal a rotten apple, which was the single most frightening and disgusting thing I did while visiting Chernobyl.

This was not a museum of Soviet history; this was Turgenev and Dostoyevsky, the Russian peasant in his element, with a sprinkling of radionuclides thrown in for modernity's sake. "One tragedy after another," Ivan bemoaned. He tried to explain further, but he spoke with an exceedingly heavy Ukrainian-Belorussian accent, and so we left things on that melancholy note.

A NEW ARK, AND ARCH

While the samosels live in dishearteningly primitive conditions, the power station itself has the attention of the West's finest engineers. Much of the Exclusion Zone can be allowed to remain in ruin-except, paradoxically, the thing that caused the devastation.

Sarcophagus comes from the Greek σαρκοφάγος, which roughly means "flesh-eating," a reference to the limestone tomb within which decayed one's earthly remains. The one that was erected around the reactor in the seven months following the meltdown is a brutally wondrous thing to behold: about 400,000 cubic meters of concrete and 7,300 metric tons of steel, all of it as gray as a November sky. Remarkably, it has held a radioactive crypt whose contents we don't fully know and never want to see. Most everyone is sure that the sarcophagus can't hold much longer, having weathered nearly 30 winters so brutal that their predecessors sapped the armies of both Hitler and Napoleon (the summers aren't exactly clement, either).

In the winter of 2013, a portion of the turbine hall collapsed. With brazen nonchalance straight from the Brezhnev years, a spokeswoman for the plant deemed the event "unpleasant."

James Mahaffey, a nuclear engineer and the author of the recent book Atomic Accidents, told me that while the sarcophagus was necessary, it was "all wrong. You don't just drop concrete on a burning reactor." Not that there were many options (or any aesthetic considerations) in the wake of the catastrophe, but the concrete sarcophagus erected under hellish conditions in seven months essentially serves as a thermal blanket, keeping warm the radioactive elements inside (some of these have melted into a nuclear lava called corium, the most notorious deposit of which is called the Elephant's Foot). It has been upgraded, but you can only do so much with an '81 Lada. Everyone knows the sarcophagus has to go.

Mahaffey is not circumspect about what worries him most: "Russian concrete. Russian this and Russian that." He lists a variety of dangers: wind blowing through gaps in the reactor, dispersing radionuclides; rain leaching off same. He later wrote, "I left out birds, insects, migrating animals, tourists, changing of the guard, and sporing bacteria."

"It wouldn't take much of a seismic event to knock it down," a civil engineer recently explained to Scientific American. The Federation of American Scientists says, "If the sarcophagus were to collapse due to decay or geologic disturbance, the resulting radioactive dust storm would cause an international catastrophe on par with or worse than the 1986 accident." Eater of flesh indeed.

Nor is the land surrounding the reactor quite the pristine preserve that some have celebrated in nature-has-triumphed-over-our-thoughtlessness-and-incompetence fashion. Earlier this year, a study by University of South Carolina biologist Timothy Mousseau and others indicated that fallen trees weren't decomposing because, in Mousseau's words, "the radiation inhibited microbial decomposition of the leaf litter on the top layer of the soil," turning the ground into a vast firetrap at whose center sits the aged sarcophagus.

So, at best, Chernobyl is merely dormant. To extend that dormancy for a lot longer, Novarka was contracted in 2007 to build the New Safe Confinement. Though sometimes described as a gigantic hangar, having seen the NSC, I see it as something more elegant, its hopeful parabolic curves recalling the smooth grace of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. In cross section, it is two layers of steel with a 39-foot layer of latticework in between. Its combined shapes and angles are so fluid and simple, you want to put them on a ninth grade geometry quiz.

Currently being built in two pieces, it will rise 30 stories and weigh 30,000 tons-and cost perhaps as much as $2 billion. When completed, the steel contraption will slide along Teflon rails on top of Reactor No. 4 (a process that will take several days). It is believed to be the largest movable structure on Earth. The NSC will be so enormous that, according to the British technology journal The Engineer, it "is one of a handful of buildings that will enclose a volume of air large enough to create its own weather."

Chernobyl is on the border with Belarus, far from both Crimea and the eastern borderlands where Russian forces have belligerently gathered. And yet the conflict between Kiev and Moscow could have repercussions here. A report on FoxNews.com, for example, surmised that Western nations funding the NSC "may be leery of investing amid political instability." The article has an economist wondering if Russia will "use completion as yet another bullying point to continue their moves on Ukraine."

This may be a pure linguistic accident, but Novarka sounds like a Slavicized contraction of Noah's ark. Yes, I am acutely aware that ark and arch might for some seem to be homophones, and not even good ones at that. Yet the more I think about the association, the more sense it makes: This arch, like that ark, is supposed to save us from our own sins and folly. Though, admittedly, the metaphor only goes so far. It would not be water, this time, prevailing upon the earth, but a pestilence invisible and unlikely to ever recede.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF PROMETHEUS

Katya, my Virgil through the Exclusion Zone, estimated that 90 percent of the tourists who come to Chernobyl are just "checking a box." I was checking a box, too, one that had remained empty ever since my father made his strange warnings 28 years ago about the Leningrad sky, which was as overcast that spring as it was every spring for which my memory was available. What was up there, all of a sudden, that I needed to avoid?

"This is a lesson for humanity," Katya told me as we walked through town. But what lessons, exactly, Ukraine has learned from Chernobyl are not clear. Some people put the death toll in the mere dozens, these being mostly of the first responders who entered the reactor without the benefit of proper protection. Others think that, when all the cancers have run their course, the fatalities will be in the six figures. The World Health Organization says that Chernobyl claimed 4,000 souls. But nobody truly knows.

Nor did Chernobyl put an end to nuclear energy in Ukraine. According to the World Nuclear Association, Ukraine "is heavily dependent on nuclear energy-it has 15 reactors generating about half of its electricity." And the hostilities with Russia have renewed calls for Ukraine to regain its status as a nuclear superpower. As one Ukrainian politician explained, in what seems to be textbook realpolitik, "If you have nuclear weapons, people don't invade you." Yeah, maybe. But yikes.

"Humanity learns mostly by disasters," Hans Blix told me when I reached him by phone at his home in Stockholm. As head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, he was the first Westerner to see the ruined reactor, flying over it in a helicopter about a week after the disaster. "It was a sad sight," he recalls. The graphite moderator was still aflame; he jokingly likens it, today, to "burning pencils."

Pliny the Younger, writing of the destruction of Pompeii in A.D. 79 by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, described how "a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood.... We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room."

Yet the most curious aspect of Pliny's letter to Tacitus is the following: "There were people, too, who added to the real perils by inventing fictitious dangers: some reported that part of Misenum had collapsed or another part was on fire, and though their tales were false they found others to believe them. A gleam of light returned, but we took this to be a warning of the approaching flames rather than daylight." It is almost as if Pliny is offering a rebuke against excessive despair at the moment that Pompeii was facing certain doom. It's hope against hope.

Chernobyl is a similar amalgam of fears real and imagined, of Chernobyl Diaries alarmism combined with sobering tales about the limits of human power. You are reminded of the latter by a statue of Prometheus that today stands at the power station. Originally, that statue stood in front of the movie theater in Pripyat, which was also called Prometheus, the metallic lettering (Прометей) still affixed to the facade, a three-syllable battalion weary and weathered by battle.

Prometheus! It's like they knew.