Before long, we might see a new twist on those Cialis TV commercials, in which the fit, earnest guy with gray hair will say into the camera: "The algorithm my doctor prescribed tells me the peak time to surprise my wife in the shower."

Pills are about to get smart, and that's going to vastly increase the value and efficacy of medicine. For all of history, pills have been dumb—they don't know anything about you, or whether they're working well, or if they'd be working well if only you weren't such a doofus and took them as instructed.

To get smart, pills don't need some radical transformation, like arming them with an ingestible computer chip and wireless transmitter. Instead, when you fill a prescription in the coming years, you'll get a bottle of pills plus software that analyzes biological data from your phone, wrist monitor, networked bathroom scale and even your digitized dinner fork, to figure out if the drug is working and whether your doctor needs to modify the dosage. It will funnel all that data into an app intended to engage you in your treatment, because if you see progress, you're more likely to keep taking the drug.

Until now, drugs have been the end product of pharmaceutical companies. Going forward, drugs will be more like drugware—just one part of a solution designed to guide you to wellness. A drug without software will come to seem as inadequate as Lady Gaga in street clothes.

"The idea is to sell the outcome," says Glen de Vries, co-founder of Medidata Solutions, which runs the technology part of clinical trials, collecting and sorting data from thousands of patients and doctors as they test a new drug. Some of the ideas on how to do drugware, says de Vries, are growing out of the software increasingly used in such trials and adds "The industry is cautiously testing combinations of drugs and algorithms," he adds.

That's different from existing gadgets, like the automated insulin pumps used by millions of diabetics. Those gadgets take readings and then automatically inject insulin. Some deliver data about glucose levels to apps, but the devices are aimed at automating a physical chore. Coming drugware will have a goal of augmenting intelligence about your health.

It's like the classic insight that when you buy a drill, you don't really want a drill—you want a hole. Sick people don't necessarily want drugs—they just want to feel better. Turning drugs into drugware would mark a major perception shift in health care.

A few things are driving this. One is the sheer volume of health-related devices and apps flying at us from the technology industry, giving us intimate data we previously either couldn't know or didn't want to know.

Withings, for example, makes a $150 scale that does way more than show your weight. When you step on it, it records your heart rate and body mass index. For good measure, the scale measures air quality in the room and, Withings claims, "lets you know when to clear the air." Since these scales are typically placed in bathrooms, this could be an embarrassing feature.

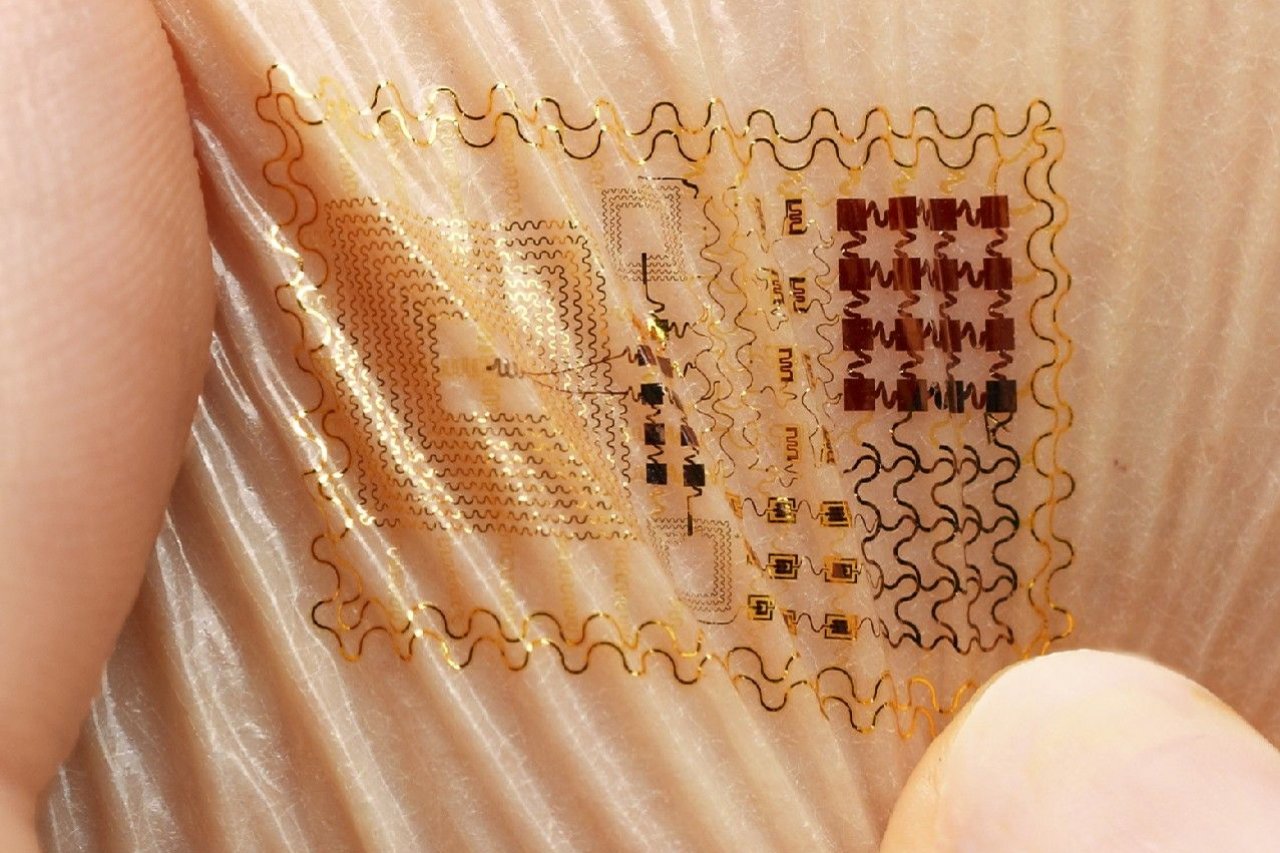

The scale delivers all its data to a smartphone app, which sorts and charts the information. All kinds of other gadgets take health and activity readings—Fitbit and apps that track sleep patterns—but new gadgets are getting even more sophisticated. In March, Vital Connect unveiled a Band-Aid size patch you can stick to your chest. It can track heart and respiratory rate, skin temperature, body posture, steps and even stress levels. In the same month, researchers working in South Korea and Texas, along with manufacturer MC10, unveiled a patch called Biostamp that can gather data about the user's skin and muscles as a way to track the onset of Parkinson's disease.

For now, bio-devices typically send data to their own, closed apps. Companies such as Medidata are looking at ways to move that data—with permission from the device wearer—from personal devices into software that could work in tandem with a drug.

Technology isn't the only force driving interest in drugware. Obamacare plays a role. Doctors will now make more money when patients get well and stay well. If a drug app can help, you can bet doctors will prescribe those apps.

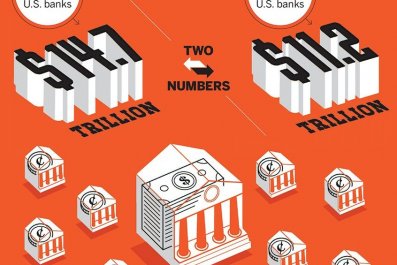

Drugware might trim the cost of health care for all of us. Only about half of people on chronic medication take their pills, according to a 2013 study. When people don't take their meds, they wind up getting sicker. Medication nonadherence, to use industry parlance, adds around $100 billion in annual health care costs in the U.S.

One promise of drugware is that it will understand context and influence behavior beyond just coaxing you to take your pills. If part of getting better requires you to lose weight or cut back on alcohol, an app could track that too. In fact, physical therapy will likely come with an app to help patients follow through and track progress.

Another drugware driver will be the economics for drugmakers. They'd like to sell apps and ongoing digital services along with their drugs. It's also possible that combining an app with a drug could renew the patent on a drug that's about to expire. One way or another, says de Vries, "if you add an app to a drug, it raises the value of the drug."

Major pharmaceutical companies are just beginning to think about digitizing drugs. Merck founded a unit called Vree Health a couple of years ago to explore "technology-enabled services." So far, Vree has developed technology that helps doctors track their patients' care—not apps for patients. None of the big drugmakers have yet announced major drugware efforts.

The ideas here are still so new that regulators don't quite know where to step in. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued what it called Mobile Medical Applications Guidance last fall, but the document basically says the FDA is keeping an eye on apps and will "focus only on the apps that present a greater risk to patients if they don't work," and on apps that connect to medical devices like pacemakers. You really don't want a software bug to crash your pacemaker.

If the agency decides it must regulate the algorithms and software that work with drugs, we'll end up with something new: prescription apps.