Gussie Maccracken, a paleontology intern, sits down on the sloping hill to dust off rocks with a small paintbrush, her back turned to the giant container ships making their way quietly down the Panama Canal.

"Oh, I found something!" the 25-year-old Ph.D. candidate squeals, holding up a small rock with a darker hued, fingernail-sized protrusion. A few feet away, Caitlin Colleary, also a paleontology intern and Ph.D. candidate, soon echoes Maccracken's triumphant cry. For four months, the young American scientists have been waking up before sunrise and spending their mornings sifting through a fossil field on the banks of the canal.

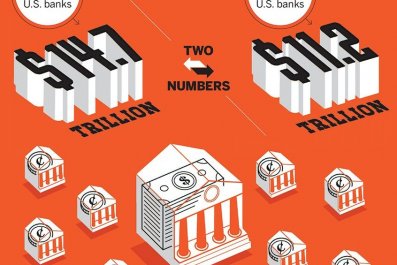

To accommodate increasingly large container vessels, engineers have been expanding the Panama Canal since 2007—the most ambitious project since the waterway's original construction at the turn of the 20th century. One unlikely winner of the $5 billion engineering project? The scientific community. Investigators affiliated with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), a bureau of the Washington, D.C.-based institution, have been trailing behind demolition teams and collecting the freshly exposed fossils.

Already, the group has determined that the isthmus between North America and South America began rising approximately 21 million year ago, not 3.5 million, as had been commonly thought. This means that the Pacific and Atlantic oceans split apart—and the flora and fauna of the two continents coalesced—earlier than assumed. "Geological history is far more complex than what we had been thinking until now," says Carlos Jaramillo, a staff scientist at the STRI.

When the isthmus emerged and halted the exchange of water between the Atlantic and the Pacific, salinity in the former rose, depleting the Caribbean of certain nutrients, making the water more crystalline and giving birth to the coral reefs for which the sea is known. This denser water helped give rise to the global ocean conveyor belt, in which warm, fresh water is transported north and cooler salty water flows south of the equator and on to Antarctica, where it warms the cold bottom waters and helps them rise to the surface. The system distributes heat and moisture around the planet.

The implications of the project are vast for the scientific community, but for the investigators combing through the banks of the canal, the experience carries overwhelming personal weight. "This is 21 million years old, and I'm the first person to see it," said Colleary, 29, clutching a rock that might have a fossil embedded in it. "That's what gets to me."

Maccracken's eyes sparkle as she reminisces about the fossils she has found, including the toe of a giant beardog, an extinct dog-like animal that was as big as a black bear and which migrated to the isthmus from North America. Other investigators have found fossilized remains of miniature camels, horses, monkeys, rhinos, caimans and bats. Fossils of fruits and flowers have also been found, revealing a forest with tropical elements, says Jaramillo. Many of these contain a mixture of elements from North America and South America.

Wearing orange vests and hard hats, the investigators apply sunscreen, wander around until they choose a work area for the day and then lay out their tools: dental picks, brushes, screwdrivers and rock hammers. For the next three hours, they are not distracted by the container-laden ships or the workers nearby or by the geopolitical significance of their surroundings; instead, the scientists are focused intently on the minuscule time capsules from the Miocene Epoch that they dig up, break apart, inspect and dust off.

It is a fight against the clock, as canal workers move in to seal the dredged soil quickly in an effort to prevent landslides. Investigators have anywhere from a week to three months to sift through any given site before they are ushered out. When a contractual dispute halted construction for two weeks in February, a tremor went through the global shipping community, but for Jaramillo, it was welcome news: It bought his team of scientists more time.

Dredging has unearthed not only fossils but also archaeological items such as a 16th century Spanish dagger and pre-Columbian arrowheads, according to the Panama Canal Authority. These have been restored and preserved.

By now, the expansion project is nearly three-quarters completed. The pace of dredging has slowed, and engineers have begun shifting their focus to the design and construction of the locks that will raise and lower ships as they pass through the 48-mile canal. During the first few years of the expansion, as many as 20 scientists would scour the dredge sites daily; that number has shrunk to around five. The expansion is expected to be finished by December 2015.

The $6.5 million dig for fossils was financed with grants from the Panama Canal Authority, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Geographic Society and a private donor.

On a recent morning, Maccracken and Colleary made their way back from the canal to their lab, a large complex at the Cerro Ancon, a 653-foot hill overlooking Panama City, and unpacked their day's finds at a communal table. Maccracken, who suspected the palm-sized rock she brought back contained a fossilized shark tooth, said if the meticulous cleanup did not yield a positive identification, she would send the object to the University of Florida, a partner in the project, for further tests.

The collaboration with Florida extends well beyond the state university. Bruce MacFadden, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, said some of the fossils collected at the expansion site will be put on display at the museum in August in honor of the Panama Canal centennial celebration.

The most impressive fossils recovered by Jaramillo's team will remain in Panama. The Frank Gehry-designed Museum of Biodiversity, slated to open in May in Panama City, will house a 6-million-year-old marlin skeleton embedded in a rock found at the expansion site, which MacFadden calls "spectacular." Original shells and replicas of bone fragments from the canal will also be on display at the museum, an asymmetrical, brightly colored structure which stands out at the mouth of the canal and against the city's growing skyline.

A fine-grained limestone that is 15 million to 16 million years old and slightly bigger than a soccer ball greets visitors near the entrance to the museum. Further along, a room covered almost entirely in projection screens—including under the glass floor and on the high ceiling—runs a larger-than-life montage of frogs, whales, turtles and wild flowers found in Panama while a soundtrack of thunderstorms and waterfalls envelops visitors.

The majority of fossils gathered at the canal—mostly miniature fragments that are impossible for the untrained eye to imagine as being part of an animal bone or plant—end up bagged and numbered in a single-story warehouse near the lab. Housed within the Panama Canal Authority compound, the depository is filled with green, yellow and blue plastic crates stacked chest high. Each crate contains dozens of individually labeled pouches: "Crocodile skull," "turtle fragments" and "bone fragments" are well represented. Shells rest inside smaller, clear storage boxes.

In addition to the items recovered from the Panama Canal, there are fossils from Santander, Colombia. Inspired by the wealth of information he dug up in Panama, Jaramillo helped convince the Smithsonian Institution and the Colombian Geological Service to implement a paleontology rescue project where Isagen, the third largest power generator in the country, was building a dam last year. Where massive engineering projects shuffle the earth, "it is worth investing a little bit on science," says Jaramillo.