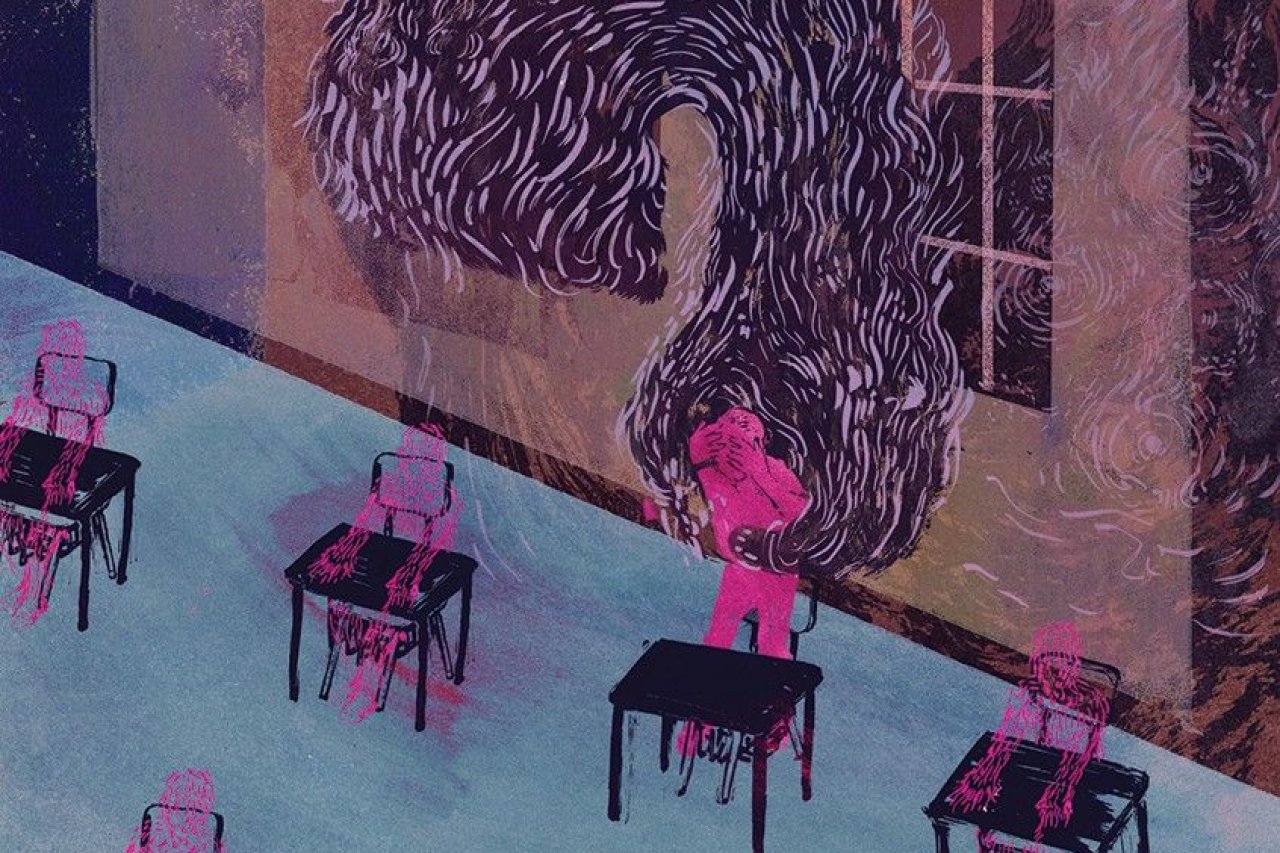

Chuck has had vivid nightmares his whole life. When he was a kid, he dreamed about being attacked on a battlefield, with the dead bodies of family members strewn around him. Once every few months, he would dream that he was drowning. "I'd wake up sweating, with my heart pounding," he says.

Nightmares are common in preschool and elementary-school children. Kids often dream about being chased or falling from great heights and then are startled awake just before being caught or hitting the ground. Most children outgrow their nightmares, however, and the latest research suggests that if nightmares persist, they could be evidence of a deeper problem.

Chuck, now 20, was still having regular nightmares by the time he was a teenager, but instead of facing down monsters, he was confronted by social rejection. In one familiar scenario, he was naked at a party that his academic adviser happened to be attending, and he remembers feeling "very exposed and vulnerable." Now a college student in Memphis, Tenn., Chuck (who asked to remain anonymous) still has nightmares. He was also recently diagnosed with schizophrenia.

It turns out that nightmares and psychosis may be connected. A team of researchers led by Dieter Wolke, a psychology professor at the University of Warwick in the U.K., recently found that children who had frequent nightmares between the ages of 2 and 9 were about one and a half times more likely to have a psychotic experience in early adolescence.

Psychotic experiences, which include delusional thoughts and auditory and visual hallucinations, are usually nothing to worry about in young children, who often have trouble distinguishing between reality and make-believe. During adolescence, however, such experiences are more unusual and may be a sign of burgeoning mental illness.

Chuck's first clinically significant schizophrenia symptoms came out at 18, when he began to suspect that his friends were informing on him to school administrators. He also started thinking he was being watched 24/7 by cameras in his dorm room, and by the time he was 19, he was "hearing voices all the time."

{C}

But while his diagnosis didn't come until college, he remembers having delusional beliefs early on. When Chuck was 11, he thought he had caused his aunt to have a miscarriage with his mind. "I would sometimes get very strange ideas," he says. "Like, I would spend days reading and watching shows about life on other planets." Between the ages of 15 and 17, his strongest hope was to be contacted by aliens. His friends found his obsession with extraterrestrial life a little weird, he says, but most dismissed it as a mild eccentricity.

At the same time, he was having nightmares about once every two to three months—a high frequency for a teenager. They mostly involved themes of "losing control, being in chaotic situations," he says. The dreams were distressing, but his parents generally shrugged them off.

The potential link between nightmares and psychosis has intrigued researchers for decades. It's easy to see why: One of the most noticeable characteristics of schizophrenia—hallucinations, or seeing or hearing things that aren't there—could be interpreted as "dreaming while awake," says Nirit Soffer-Dudek, a psychologist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel. One early hypothesis was that people who develop schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are higher in a personality measure known as "transliminality," meaning that their border between sleeping and waking states is more fluid than that of other people.

Indeed, a significant body of research has indicated that people with schizophrenia tend to have more nightmares than the general population. In a 2009 study, for example, young adults with schizophrenia reported more frequent nightmares than control subjects.

Building off of this work, Wolke and his team sought to find out if it is possible to trace schizophrenia back to childhood nightmares. They followed almost 6,800 children born in the U.K. between 1991 and 1992 until they reached the age of 12. About 75 percent of them had at least one bout of regular nightmares at some point during their first nine years, according to their parents. But by the time the children turned 12, only about 25 percent reported having recent nightmares.

The children in that last group were three and a half times more likely to have had a recent psychotic experience. "It's pretty well established that these things overlap. I think the big question now is why," says Erin Koffel, a clinical psychologist at the U.S Department of Veterans Affairs. The study, she says, helps "get at kind of the chicken-and-egg problem. Which came first: the sleep problem or these daytime symptoms?"

The answer may be neither. Recent research suggests that, rather than one causing the other, nightmares and psychotic experiences in adolescents may be linked by a third factor: stress.

"Nightmares occur more frequently when you have been exposed to trauma. They also occur more frequently if you are anxious or have had something highly stimulating happen during the day," says Wolke. And chronic nightmares are directly connected to stress: Studies show that they commonly follow experiences with war and violence, and frequently with childhood sexual abuse. Recurring nightmares also are among the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Likewise, psychotic experiences may originate in anxiety and stress. For example, people (even those without a mental health disorder) are more likely to hear voices after suffering a loss or a trauma, such as the death of a loved one. And psychosis-inducing stressors can also often be traced back to childhood. In a study from 2012, individuals who had auditory and visual hallucinations were more likely to have experienced emotional and sexual abuse in childhood, compared with a control group with no hallucinations. Other research, including an upcoming study by Wolke, indicates that many children who have psychotic experiences in adolescence were bullied in school.

Some psychologists hypothesize that trauma causes people to experience a loss of agency and disassociate, stepping outside of oneself into a fantasy world. "One of the main symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder is this kind of reliving of the event and seeing it play out in front of you, as well as having quite severe nightmares," says Helen Fisher, an anthropologist at Rutgers University who co-authored the paper. "That often happens when someone has experienced a stressor and doesn't process it properly."

Chuck's female swim instructor molested him when he was 5, he says, and he was constantly bullied until around his freshman year of high school. As an open atheist in an all-boys Catholic school, he felt ostracized and was targeted for being different. "I just lost my will to fight back," he says.

The combination of being bullied at school and maltreated at home leaves children with 24-hour days filled with fear and uncertainty, says Wolke. "How can you deal with a world that is so stressful?" he asks. "So you perhaps create your own world, or you become hypersensitive—you see problems everywhere, and you feel persecuted even though these experiences are not real."

Chuck is doing well now. He made the dean's list last semester, has many good friends, and stays active—he recently started power lifting and will compete in a tournament later this year. But he was relatively lucky—he got therapy and found an antipsychotic medication that worked for him soon after his diagnosis.

Wolke and others hope that understanding the factors that contribute to psychosis can help clinicians steer children at risk of mental health disorders into early interventions sooner. "We are realizing that once people have developed a mental disorder, then it's pretty tough to do something about it," Fisher says. But providing them with treatment early on can dramatically improve their prognosis, she adds.

It's easy for parents or family members to miss a child's struggles with mental problems like depression or psychotic experiences. After all, children don't know what's "normal" and are unlikely to be able to share experiences that adults might interpret as warning signs. And if troubling signs do come up, doctors must closely monitor them, says Ian Kelleher, a psychiatrist at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Nightmares, on the other hand, are easy to spot.

Of course, "having nightmares doesn't mean that your child is mentally unwell, and it doesn't mean they are having psychotic experiences," says Kelleher. "But it does highlight the fact that when they are having persistent nightmares, you need to ask what's going on in their life." In addition, while the link between nightmares and psychotic experiences is clear, the vast majority of adolescents who experience psychotic symptoms won't develop schizophrenia. Most will go on to have another, non-psychotic disorder, however, such as depression, ADHD or anxiety.

And it's too early in the game to think about diagnosis-specific interventions, Fisher says. But fairly noninvasive treatments—such as bolstering coping strategies and self-esteem, and making sure people have strong support networks (things that are probably generally useful for teenagers anyway)—could help adolescents deal with underlying stress.

The terror of nightmares is usually fleeting, but in some cases it's better to investigate than sit back and hope for the best.