Is Big Tobacco color blind?

Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, former secretary of health and human services under President George H.W. Bush, for one, doesn't think so.

Sullivan says it's no accident so many black smokers are hooked.

"You go into convenience stores in the black community, and you see these ads plastered all over the windows and doors about Kools and Camel menthol cigarettes," says Sullivan, who is leading a recently launched campaign to get U.S. health authorities to ban menthol cigarettes. "When you go into a similar convenience store in a white community, you don't see ads like that."

Each year, smoking-related illnesses kill more black Americans than AIDS, car crashes, murders and drug and alcohol abuse combined, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). More than four in five black smokers choose menthol cigarettes, a far higher proportion than for other groups.

Menthol, found naturally in mint plants, brings a fresh, cooling sensation to smoking. By mitigating the harshness of cigarettes and numbing the throat, menthol makes smoking more palatable, easier to start—and harder to quit. These mellow effects have propagated the misconception that menthol cigarettes are less harmful than other cigarettes.

About a quarter of all cigarettes sold in the U.S. are menthol. As non-menthol cigarette use sharply declined between 2002 and 2010, menthol cigarette use among African-American smokers has soared from an already lofty 69 percent to 85 percent, according to a new white paper from CASAColumbia, a science-based organization affiliated with Columbia University that develops solutions for addiction.

Today, the proportion of black smokers who smoke menthol cigarettes is nearly three times that of white smokers. Many experts say the main reason for that is marketing.

"We are specifically targeted by the tobacco industry to smoke them," says Delmonte Jefferson, executive director of the National African American Tobacco Prevention Network.

The campaign to ban the product has gathered steam. Earlier this year, every living former U.S. health secretary and surgeon general and every CDC director—a bipartisan group of 20 from every administration since President Lyndon B. Johnson—called on tobacco giants Philip Morris, Lorillard and R.J. Reynolds to stop selling and marketing menthol cigarettes. The group, the Citizens' Commission to Protect the Truth, also urged the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ban menthol as a characterizing flavor in cigarettes.

"When we met with members of Congress, we said that this really gives an impression that the lives and health of black youngsters and the black community are less important than those of white youngsters," says Sullivan, the commission's vice chair. "Congress didn't like that. It got very angry reactions. Well, then, why don't you ban it?" he asks rhetorically. "If this was something in the white community, our impression is you wouldn't take 10 seconds to pass legislation banning that."

Robert Bannon, a spokesman for Lorillard, which makes Newport, Kent and True brands, says the company believes the recommendations of the group are "not supported by science."

"We acknowledge that smoking is injurious to health, but menthol cigarettes are no more harmful than non-menthol cigarettes," he says.

In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act banned all flavored cigarettes—except menthol. Though the act fell short of banning menthol, it authorized the FDA to regulate tobacco products. The FDA has not yet acted, despite overwhelming evidence that banning menthol cigarettes from sale would greatly benefit public health and save lives.

Asked for comment, the FDA said it is "currently considering all comments, data, research and other information" before making a decision on whether to take action on menthol.

Jefferson says menthol is a huge share of the market. "If you give up menthol, you give up significant revenue, from an industry standpoint," he says. "It's obviously racially motivated."

The industry denies that.

"Lorillard responsibly markets its products to adult smokers, age 21 and older, including those smokers who prefer menthol cigarettes," says Bannon. "Lorillard's marketing activities are not disproportionately directed to African-Americans or other minority groups."

R.J. Reynolds, which sells Camels and Kools, does not plan to stop marketing and selling menthol cigarettes as long as the FDA allows it.

"Our array of marketing efforts is designed to include elements of interest for all adult menthol smokers—regardless of their ethnicity or gender," says Richard Smith, a company spokesman. "Our goal is to try to increase our U.S. market share by offering adults who choose to smoke a wide variety of brand choices and styles."

Sullivan has spent his career advocating for greater health care access, education and opportunities for minorities. He grew up in the Jim Crow South, in the small town of Blakely, Ga., and earned his medical degree at Boston University School of Medicine in 1958, where he was the only African-American in his class. He says the only time he smoked a cigarette was on a dare, at the age of 12.

"I look at the tobacco industry as a predatory industry," he says. "They're willing to kill people in order to earn a profit."

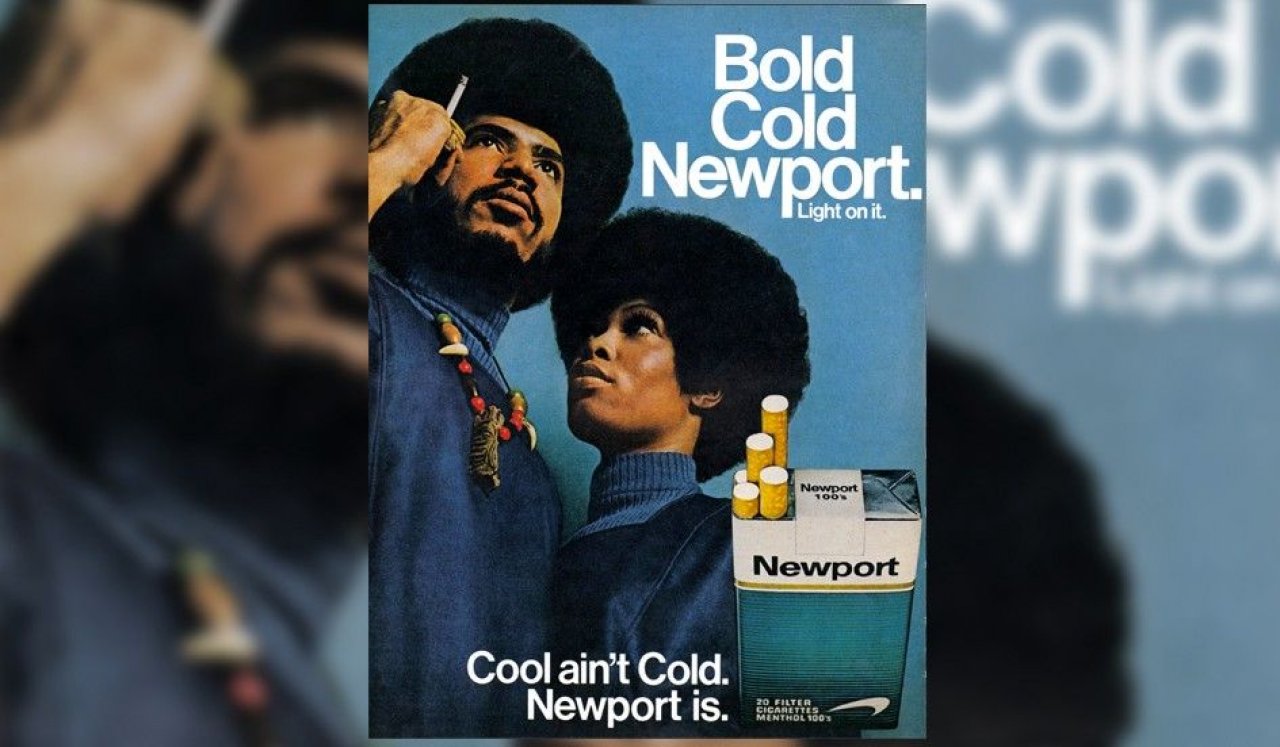

Cigarettes and African-Americans have been intertwined since slaves first worked in tobacco fields. In the early 20th century, tobacco companies used caricatures of African-Americans as savages, mammies and servants to push their products.

Spud was the first brand to add menthol to cigarettes, in the 1920s. One ad read, "Sore throat? Time to give it a rest!" Menthol ads played up the minty, fresh taste, encouraging the myth that menthol cigarettes were safer than straight cigarettes.

By the early 1950s, menthol cigarette rates were only marginally higher among African-Americans versus whites (5 percent of black smokers smoked menthol compared with 2 percent of white smokers, according to CASAColumbia). It was this slim margin that drove the tobacco industry to target the black community.

As black athletes, musicians and celebrities gained national popularity, Big Tobacco acquired new bankable pitchmen. Boxer Joe Louis and baseball player Jackie Robinson advertised Chesterfields. Willie Mays lent his image to Dual Filter Tareyton. One Kool print ad from the early 1970s evoked Al Green's album I'm Still in Love With You.

In the late 1980s, R.J. Reynolds developed a new cigarette brand, Uptown, aimed at the black community. Before Uptown came to market, Sullivan, by then surgeon general, condemned the company for deliberately exploiting African-Americans. It was the first time a Cabinet member had ever denounced a brand, and it worked: Uptown never launched.

The tobacco industry also positioned itself as an ally of the very community it was seducing, saluting Black History Month as well as the work of Martin Luther King Jr. "Our events, our colleges, our schools—anything in the African-American community, you could find the tobacco industry with a handout," says Jefferson.

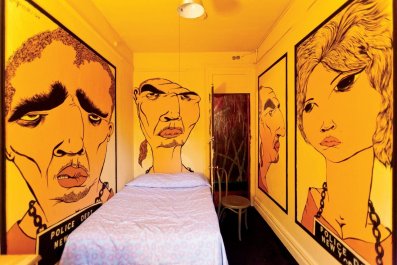

Ebony, the monthly magazine that bills itself as the "No. 1 source for an authoritative perspective on the Black-American community," has a long history of running tobacco ads aimed at blacks. In an October 1995 letter obtained by Newsweek, an Ebony executive wrote, "With a readership of over 11 million per month, Ebony serves as [tobacco company] Newport's main gateway to the African-American consumer market."

Dr. Robert Jackler, professor and chair of otolaryngology at the Stanford School of Medicine and founder of Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, has analyzed Ebony magazines since the 1940s and discovered it ran 59 cigarette ads in 1990, 10 in 2011 and 19 last year.

Ebony published 21 articles about breast cancer and 11 about prostate cancer between 1999 and 2013 but did not publish a single full-length story on lung cancer in that 15-year period. "Tobacco advertising is a huge revenue stream," says Jackler. "Ebony professes itself to be the so-called 'heart and soul and voice of the African-American community,' and it completely neglects smoking."

A spokeswoman for the magazine wrote in an email, "Ebony has covered a variety of health articles from 2000 to 2013 that have a negative impact on the African-American community." Asked about the lack of lung cancer coverage, the spokeswoman said the magazine plans to cover the disease in the future.

"The black press in general, almost without exception, takes a lot of these ads," Sullivan says. "People who know better are not being responsible."