On January 21, 2010, a cold, clear day, Dean Pierson woke up early, as usual. The 59-year-old put on a pair of blue jeans and a hooded coat before the sun was up, then went to his barn, turned on the lights, closed all the doors and windows, powered off the fans and cranked up the volume on the radio. He then shot each of his milking cows with a .22-caliber N1 carbine rifle, about 51 of them, between their horns and eyes, hitting their brains and killing them instantly. Pierson then sat down in a wooden chair with an upholstered seat, pulled a ski mask over his face, picked up a 12-gauge pump-action shotgun and shot himself once in the chest.

Around 9 or 9:30, a truck driver from the Agri-Mark co-op arrived to collect milk from Pierson's tanks. The driver saw a note attached to the barn door warning whoever found it not to enter and to call the police. He called his dispatcher, who called Pierson's milk inspector, who telephoned Bill Kiernan, the farmer next door.

Kiernan sent his grown son, Walter, and an employee to check on their neighbor. On the way to the barn, Walter ran into Dean's mother, Pauline, who lived on the farm and happened to be out walking down the road. The two of them entered through the side door while the employee went through the back. Walter spotted Pierson first. Behind the blood-soaked chair, on a narrow wooden desk attached to the wall, were two notes written on yellow cards used to tag cows. One of them had words and phrases written like bullet points: Lonely. Discouraged. Overwhelmed. No hope. Can't go on. Danger to my family. Worn out. The kids are so talented. Gwynne you are a good person. The other note simply said, So sorry.

The state police arrived shortly after 1 p.m. "It was perfectly quiet, no rattling around of cows in their stalls," recalls investigator Kelly Taylor. George Beneke, a veterinarian, came dressed in coveralls and boots and brought a stethoscope to determine which cows were dead, although he didn't need it. By that time the cows were bloated, and they had all fallen backward in identical positions. "He was pretty efficient," Beneke says of Pierson. "He knew how to kill a cow."

A Suicide Every Two Days in France

For decades, farmers across the country have been dying by suicide at higher rates than the general population. The exact numbers are hard to determine, mainly because suicides by farmers are under-reported (they may get mislabeled as hunting or tractor accidents, advocates for prevention say) and because the exact definition of a farmer is elusive.

People started talking about farmer suicide during the 1980s farm crisis. By the 1960s, technical innovations had made farming easier, and farmers were expanding operations by taking out loans. But the 1980s brought two droughts, a national economy in trouble and a government ban on grain exports to the Soviet Union. Farmers started defaulting on their loans, and by 1985, 250 farms closed every hour. That economic undertow sucked down farms and the people who put their lives into them. Male farmers became four times more likely to kill themselves than male non-farmers, reports showed. "In the West, the guys were jumping off silos," says Leonard Freeborn, a horse farmer and agricultural consultant.

Since that crisis, the suicide rate for male farmers has remained high: just under two times that of the general population. And this isn't just a problem in the U.S.; it's an international crisis. India has had more than 270,000 farmer suicides since 1995. In France, a farmer dies by suicide every two days. In China, farmers are killing themselves to protest the government's seizing of their land for urbanization. In Ireland, the number of suicides jumped following an unusually wet winter in 2012 that resulted in trouble growing hay for animal feed. In the U.K., the farmer suicide rate went up by 10 times during the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in 2001, when the government required farmers to slaughter their animals. And in Australia, the rate is at an all-time high following two years of drought.

Robert Fetsch, a retired professor of human development and family studies at Colorado State University, says there are profound social reasons farmers are reluctant to seek help. "Farmers are extremely self-sufficient and independent," he says, "and tend to work around whatever they have, because they are so determined to keep moving."

One factor disputed among agricultural and mental health professionals is the connection between pesticides and depression. A group of researchers published studies on the neurological effects of pesticide exposure in 2002 and 2008. Lorrann Stallones, one of those researchers and a psychology professor at Colorado State University, says she and her colleagues found that farmers who had significant contact with pesticides developed physical symptoms like fatigue, numbness, headaches and blurred vision, as well as psychological symptoms like anxiety, irritability, difficulty concentrating and depression. Those maladies are known to be caused by pesticides interfering with an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter that affects mood and stress responses.

"A lot of farmers are very familiar with the pesticides, so they sort of take it for granted," Stallones says. "It's an invisible kind of thing, so if you can't actually feel it, taste it, touch it, you might not believe it's an issue."

Not everyone is sold on the link between pesticides and depression. "I don't think there's firm data on that yet," says Jill Harkavy-Friedman, senior director of research at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. A greater contributor to suicide in rural areas, she says, is the easy access to guns. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most suicides in America involve firearms, and more than half of all firearm deaths every year involve suicide. Harkavy-Friedman points to a 1998 study published in The British Journal of Psychiatry that showed the most common means of farmer suicide in England and Wales from 1981 to 1988 was guns. Following firearm legislation in 1989 that reduced access to guns, the total number of farmer suicides went down.

That's good news in Britain, but not much help in America, says agricultural consultant Leonard Freeborn. "I don't think you're ever gonna find a farm without a gun [here]."

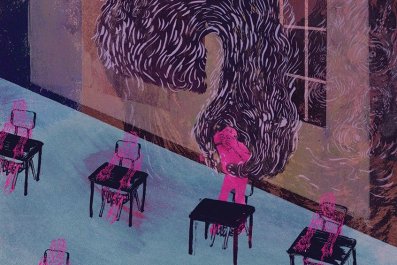

{C}

Running on Milk Money

Copake is about 110 miles north of New York City, near where New York, Massachusetts and Connecticut meet. This part of upstate New York boomed in the 1940s and 1950s, when men like Dean Pierson's father started farms there because of the rich soil and close proximity to major cities. For years, Copake ran on milk money. When bulk milk tanks were introduced, farmers there and in nearby Ancram were the first in the country to get them. New technology made farming easier, and farms across the country expanded until the 1980s. Then the farm crisis hit. By 1988, the number of cows in the area was half of what it had been two decades earlier. In 2003, only 15 dairy farms were left. Roeliff Jansen High School, which trained farmers like Pierson, closed in 1999 and remains vacant, and buildings with for-sale signs surround the Copake Memorial Clock at the center of town.

Dean Pierson's father, Helmer, immigrated to the United States from Sweden with his family when he was 3. The family lived near Copake, and Helmer's father, Dean's grandfather, worked as a dairy farmer. Helmer got married in 1942, and the following year, he enlisted in the Army and fought for his adopted country in World War II as an airborne engineer.

In 1951, Helmer and his wife bought a farm, which they renamed High Low. Dean, their only child, was just 1 at the time, and he grew up helping his parents run the farm. He played high school football and participated in 4-H, as his father had. He studied agriculture at the State University of New York at Cobleskill and graduated in 1970. He then returned to High Low, helped expand it, purchasing more land and building new barns. In 1980, he took it over from his aging parents. In 1988, he married Gwynneth Oberly, 12 years his junior.

Just a few years into their marriage, things started sliding away from Dean and Gwynneth. "I could see he was getting very discouraged because it wasn't working out," says Beneke, their veterinarian. "He became a very unhappy man." In 1996, the Piersons auctioned off their cows, tractors and even their immaculate antique Ford Model T, and Dean did other work, including construction and carpentry. People in town found him hard to deal with. "I think that was really when he was starting his spiral down," says Kiernan, the neighbor.

Two years later, Pierson did something that stunned his neighbors: He reopened High Low, purchased new cattle and built a new barn full of technical innovations. A computerized feeding mechanism circulated hay bales around a track, and the "ventilating system with its four-foot fans is the first in the area," said a local paper.

A decade later, however, the 2008 recession crushed dairy farms. The government lowered its fixed price on milk, while the cost of fuel, feed and fertilizer went up. In July 2007, American farmers were getting $21.60 for every hundred pounds of milk. By July 2009, that was down to $11.30. "It was just a horrible, horrible year," says Ruth McCuin, Pierson's milk inspector at the time.

"I could see there was a change in Dean," says Jim Miller, who had known him since childhood. Pierson lost interest in hobbies like deer hunting and snowmobiling, and fell out of touch with friends. "He withdrew within himself."

"I feel lousy, exhausted, and frustrated nonstop, which leaves me with insomnia and general crabbiness," Gwynneth wrote to a college friend in January 2008. "My marriage is in name only. Dean acts depressed and seems to have a kind of dementia. He is really tough to be around as his thoughts are his only reality."

Most farms the size of Pierson's had employees or family members helping, but Dean worked alone. His grandfather had come from Sweden to be a dairy farmer. His father, who died in 2005, had achieved the American dream with High Low Farm. The burden now fell on Dean to save it, and he was in free fall. Susan Johnson, a cousin, remembers something Dean asked his wife around that time: "If I got rid of all the cows, would you love me?"

Seeds of Hope

For over three decades, despairing farmers have been able to turn to Michael Rosmann. Now 67, Rosmann grew up on a grain and livestock farm near Harlan, Iowa. He attended a Catholic seminary, intending to become a priest, but switched to psychology. He eventually took a job teaching psychology at the University of Virginia, but after four years he again started having doubts. "I felt restless the whole time there," he says. In 1979, he decided to return to farming, but planned to use his psychology skills to help farmers. When he told his UVA colleagues his reason for leaving, they snickered. "Why take care of farmers?" they asked, to which Rosmann replied, "Because somebody has to."

The basis of Rosmann's work is what he calls the agrarian imperative, the idea that humans have an innate drive to work the land and produce food for their families and communities. He says farmers take significant risks to satisfy that drive, and if they are unsuccessful, they develop a deep sense of failure. "Farmers are motivated to hang on to land at almost all cost," he says.

Rosmann helped guide farmers through the bleak 1980s. Then, in 1999, he used funding from the federal Office of Rural Health Policy to establish Sowing the Seeds of Hope, a network of agricultural phone hotlines. It connected farmers in Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin with counseling specialists. Between 2003 and 2006, around 700 callers said they were suicidal. During its entire time in operation, the hotline received 75,000 calls and trained over 4,400 professionals.

In 2010, Sowing the Seeds of Hope had to shut down due to lack of financing. "There has been a great cutback in funds with anything that has to do with agricultural safety and health. It's on the chopping block just like the food stamps program," Rosmann says. "Everything's a mess."

"I'm a Good Listener"

In 1985, when an Iowa farmer named Dale Burr killed his wife, neighbor and bank president before turning the gun on himself, a dean at Cornell University took notice. Then, after a New York farmer's suicide hit closer to home, the dean said, "This is tragic. We have to do something." That was the genesis of NY FarmNet, a free and confidential agricultural resource hotline that is similar to Sowing the Seeds of Hope but which has been operating for 28 years and continues to grow. Its headquarters are two small offices at Cornell, in Ithaca, N.Y. The goal, its four full-time employees say, is to help farmers resolve personal and financial difficulties long before there's a call about a loaded gun.

"We're not really a last-resort suicide hotline type of thing," says outreach director Hal McCabe. "We're able to identify a case and start to turn things around before it gets to the point that it is a suicide call."

When farmers call the 800 number, they talk to Racheal Bothwell. The 15-year FarmNet veteran asks open-ended questions to learn about the farmer's situation and then assigns the case to one of 47 personal and financial consultants throughout New York state, who reach out to farmers within 24 hours.

"FarmNet is essentially putting their arms around the person who is struggling," says Judy Flint, one of its consultants. "I'm a good listener." She estimates that over the years she's handled 10 to 15 cases in which farmers expressed thoughts about harming themselves. "We understand the way of existing in a farm. That puts us ahead of regular mental health providers, and I think farmers are comforted by that."

Leonard Freeborn, 82, is the oldest FarmNet consultant. "Farming is not the beautiful thing you people in the city think it is, with beautiful cows running around and you're making lots of money," he says. "Farming is a tough damn business."

Although FarmNet is not a suicide prevention hotline, its staff knows how to handle those calls. The winter before last, a dairy farmer from western New York called at 2 in the morning, saying he had a loaded shotgun at his side. "He needed me to explain to him how we understood farming before he would trust us with the situation. Calling a normal hotline was not for him," Bothwell says. She kept him on the phone for two hours until he promised to unload the gun. Instead of calling the police, she had a consultant at his farm by 8 a.m.

Last year, the hotline received over 6,000 requests for assistance. The organization's funding comes mainly from the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets and the New York State Office of Mental Health. Most of that money goes to the consultants, and the average case costs the organization only $400. "FarmNet is an investment in the state's economy," says Ed Staehr, the executive director. "It's not a cost."

"We're in a period of traumatic change," says Freeborn. "We're going to continue to see people who are depressed on these farms, and we have to have people who can spot it and get them the kinds of services they need."

"More Bags Than You Think"

Spreadsheets and calculators cover Russ and Laurie Bedford's kitchen table. Dewey Hakes, a FarmNet consultant, is there to help them do their annual operating budget. The list of costs is growing: land rent, fertilizer, equipment and facilities maintenance, computer upgrades, livestock fees, labor, fuel. Every time Russ punches a number into the calculator, he scrunches his face and then sighs at the result. The current expense up for discussion is the barn floor, which needs repairs so the cows won't injure themselves. "That will just take a few bags of cement and some work," Russ says, emphasizing the first syllable in cement.

"It takes a lot more bags than you think," Laurie says. Russ reaches for the phone to call someone for a price quote, but he accidentally grabs the television remote and dials the number on it.

The Bedfords have 95 cows on their 350-acre farm near Oneonta, N.Y., which they run with two full-time and three part-time employees. It's been a decade since they have taken more than a few days off. Russ's grandmother started the farm over a century ago, and his father transferred it to him (with Hakes's help) in 2012, when Russ was 61 and his father was 89. During the transfer, they established the farm as a limited liability company, or LLC, which separated their personal and business assets, something most farmers with smaller operations don't think to do. It took four hours to sign a stack of documents as thick as a ream of copy paper.

Russ is wearing a red long-sleeve shirt and navy blue suspenders. He sounds like an auctioneer when he speaks, lacing together unfinished sentences and ending the jumble with "I says." Laurie, wearing a blue pullover and jeans, is the frugal one. "He spends it, and I have to figure out how to pay for it," she says. Their mini poodle, Alice, is asleep at their feet. Cows smile from all over the living room and kitchen, appearing on cookie jars, napkin holders, tablecloths, curtains, wallpaper and magnets. The collection started years ago with salt and pepper shakers. "They make us happy," Laurie says of their cows, both real and otherwise.

The Bedfords are still recovering from the 2008 recession, but they know things could be worse. "I was on a farm a month ago where on the whiteboard it said, 'Welcome to death farm,' " Hakes tells them. That farmer lost three cows overnight because of cold weather. "Death is something that we deal with all the time," Laurie says about farmers.

"I've seen the days when I've been stressed enough, pissed off enough, that I think I'd be better dead," Russ says, thumbing his suspenders. "You gotta grab hold of yourself."

Death on farms is something Hakes has encountered in his seven years with FarmNet. Although he is a financial consultant, FarmNet sometimes assigns him cases involving premature deaths, since he lost his 29-year-old son to leukemia. Around 2006, Hakes visited a three-generation dairy farm after the middle-generation farmer killed himself. That farmer's father and son both blamed themselves. "I've had farmers hugging me, crying, saying, 'I'm so glad you came. I needed to talk, and I didn't realize it,' " Hakes says. The fact that he too is a farmer who lost a loved one helps him connect with people. It takes only 15 minutes of talking, he says, before "the farmer is spilling his guts" to him.

"Making Too Much Money"

A week before the four-year anniversary of Dean Pierson's death, Bill Kiernan's teenage grandsons, Wally and Timmy, are plowing snow and tending to equipment. Across the road, stick-on letters spelling out "D. PIERSON" peel from a rusted mailbox. The chopped remains of lifeless cornstalks poke through the fresh snow. Gwynneth Pierson has been renting High Low Farm to Kiernan since her husband's death. "It gives you a funny feeling," he says as he stands near Pierson's barn. "How did we end up here?"

Inside the green aluminum-sided barn are two rows, each with about 25 cows in tie-stall formation. At the front is a pen for calves, and a side room contains the large milk tanks. The patriarch of the Kiernan clan is a short, earnest, 71-year-old with hairy hands who has been working on farms since age 12. He purchased his father-in-law's dairy farm in 1972 and moved it to Copake in 1985. Walt's Dairy, as it's been called since 1927, has been expanding ever since and now totals 768 acres and has 400 Holsteins.

Kiernan attributes his success to Hudson Valley Fresh, a local dairy program that started in 2003; he joined in 2006. To participate, farmers must be located in the Hudson Valley and produce milk free of bovine growth hormone and with a somatic cell count less than 200,000 per milliliter. (Regular commercial milk usually has around 420,000 cells. The smaller the count, the more omega-3s, which can increase brain function and lower the risk of disease.) Hudson Valley Fresh has been so successful that in 2013, its dairy component had to switch from a nonprofit to an LLC. "We were making too much money," Kiernan says. His milk is more expensive than regular milk, but cheaper than organic milk, and attracts customers like upscale Manhattan markets because of its local appeal and health benefits.

Not all of Copake's farmers have been as successful, and the town recently formed a committee to address its agricultural needs. According to the results of a survey the committee sent out, five Copake farmers have operated their farms for over 50 years; eight farms have been around for over 100 years; one has even been in the same family for 300 years. The biggest challenge for local farmers, they said in the survey, is property taxes. Three Copake farmers expect to downsize operations within 10 years, and when asked what opportunities he had to make money, one farmer responded, "To sell the land and go out of business."

Soon, Pierson's land will thaw and the Kiernans will clear the fields and plant hay, not far from where they buried all his cows years ago. Elsewhere in town and across the country, farmers are preparing for the new season. With spring comes possibility and an uncertain future.

"They do what they do because they love it," says McCuin. "There seem to be too many years lately when they can't do that, and it's not right."