Somebody ought to tell Mark Zuckerberg the one about the crooked physicist, the transgender lawyer and the ex-secretary of state who tried to build a blimp-based Internet service...when Zuck was 11 years old.

Over the past 20 years, the idea of serving up broadband Internet from flying machines—blimps, drones, low-flying satellites—has made some really smart, successful people temporarily lose their minds. Today it's Facebook's Zuckerberg and Google co-founder Larry Page. They were preceded by an impressive list that includes Bill Gates, cell-phone pioneer Craig McCaw, Motorola family scion Chris Galvin and the late Alexander Haig, Ronald Reagan's zealous secretary of state.

It would be great if some super-smart people can make a sky-based Internet happen. But so far, they've only proved it can't be done.

At the end of March, Zuckerberg unveiled a new Facebook lab he will fill with aeronautics experts and space scientists. Their goal is to develop what Zuckerberg calls "connectivity aircraft" that can soar overhead and deliver Internet to people who live in remote places and have yet to discover the joy of cat videos.

To give the lab a jump start, Facebook bought a company called Ascenta, which is working on solar-powered drones that could be able to stay aloft for months. Pack the drones with broadband Internet gear, Facebook's thinking goes, and they could use radio waves to connect to devices on the ground with special antennae. If a user in, say, one of the poorest regions of India were to take a break from struggling to survive to "like" a Facebook post, the signal would go up to a drone, which would relay the data to other circling drones via laser beam, until the system could find a drone near a land tower that can receive the "like" and send it on to Facebook's data center in Prineville, Ore.

No part of this system works right now, but that's why Facebook is calling it a lab. Labs are where tech companies put things that don't work.

Google is also in this stratospheric race. Its version is called Project Loon, a name that suggests Google should at least get points for a sense of humor. Instead of Facebook's winged drone, Loon will rely on high-tech balloons—perhaps thousands of them floating in the stratosphere. They, too, would be able to get radio signals from the ground, and shoot the signals to each other until one balloon can beam the data packets down to a land tower.

Loon is part of Google X, which is Google's lab. That means Loon doesn't work yet either.

Google is running a Loon pilot program in New Zealand, which has 20 times more sheep than people. (Maybe Google Analytics picked up that sheep search to buy stuff from China on Ali-baaa-baaa.)

Given enough time, the brilliant people hired by Facebook and Google for these projects could probably develop a viable airborne Internet. But this circles back to why such efforts by other brilliant people failed at this game: Time killed them.

Any flying Internet system works on radio waves. Radio spectrum is fantastically difficult to get—a grinding, political, bureaucratic process made exponentially worse by trying to offer a sky-based international system.

Spectrum globally is governed by the International Telecommunication Union. "It takes several years to get through the ITU process," says Alex Haig, who worked alongside his father, Alexander, in the late 1990s as president of their Internet blimp company, called Sky Station. "The ITU requires massive studies. Then once approved, you have to get approvals on a national basis, in every country you're going to touch. If you get denied anywhere, you're screwed."

Add to that the problem of flyover rights. You can put a satellite anywhere you want, but operate a drone at 60,000 feet and you may have to deal with the military and civilian flight authorities in every nation you fly over.

No one can say how long it might take to get all the approvals just to turn on a sky-based Internet—because no one has ever gotten them.

And while the years tick by, as the technology gets developed and as approvals are sought, land-based wireless Internet technology, most of it using spectrum already approved for such things, keeps racing ahead, moving into unserved areas and offering ever-faster wireless Internet: 2G, 3G, 4G, public Wi-Fi.

So if past is any prologue, before a sky-based system can get deployed, it gets rendered obsolete and too expensive, and networks on terra firma expand enough to take a chunk of the customers the sky system had been counting on serving. At some point, the sky project faces reality and tells its rocket scientists to pack it in.

Microsoft's Gates fell into that quicksand. In 1994, McCaw, Gates's fellow Seattle-based billionaire, convinced Gates to join him in a project called Teledesic. The idea was to build a constellation of hundreds of low-orbit satellites to offer global broadband at a time when most people were connecting to the Internet on phone modems. Boeing invested $100 million. Saudi Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal put in $200 million. After years of delays because of technology and regulatory issues, Teledesic shriveled and disappeared.

Motorola, Qualcomm, and other international companies made plans in the late 1990s for global, sky-based networks. None offer Internet to the public today.

And then there was Haig's Sky Station, a concept that was closest to what Facebook and Google are now chasing. It drew in a group of personalities made for a Wes Anderson movie. Haig was the former general who declared he was in charge after Reagan got shot. Alfred Wong, a UCLA physicist who developed a "corona ion engine" to drive the blimps, wound up pleading guilty last year to defrauding the government. The regulatory lawyer who joined them was Martine Rothblatt, who previously went by Martin and fathered four kids. The company was driven by Alex Haig.

The system they developed had promise: One blimp at 65,000 feet above a city could have served all of the 1990s-level Internet traffic from the citizens below. A blimp could stay up for five years. But, as with the other schemes, time killed Sky Station. "We ended up licensing the technology to someone else and walked away," Alex Haig says. "Nothing's come of it."

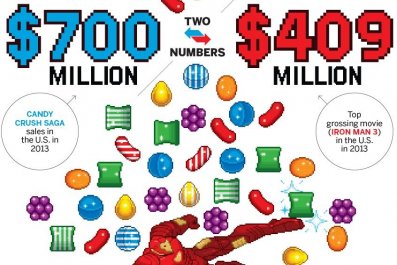

Why do smart people chase this dream? Well, "connecting the world" is an idea that makes a techie's heart race. Two thirds of the planet can't connect to broadband, though more than 80 percent of the world can now at least connect via cell phone. On paper, a sky-based system seems like an ideal way to bring all of humanity onto the network.

Then, too, it would mean new customers for Google and Facebook, though I'm sure thoughts of getting Outer Mongolians to use Google Plus don't impinge in any way on the altruism behind Loon.