There's never been a better time to cheat on your taxes. Or a better way.

As millions of Americans rush to file their tax returns on time, trying to be ever-so-careful in hopes of avoiding an audit or, far worse, prosecution, they will find it instructive, and infuriating, to learn about Jerry Curnutt.

Curnutt can show people how to cheat on their taxes and not get caught. His trick won't work if you are a wage earner, but those rich enough to invest in real estate partnerships have escaped paying billions of dollars in the past decade by using this technique.

Curnutt knows this because he is a tax detective. He retired from the Internal Revenue Service in 2000 as one of its top snoops, overseeing all investment partnerships. Using his desktop computer, Curnutt discovered a simple way to cheat that no one at the IRS had noticed. Call it Curnutt cheating.

For his brilliant sleuthing, the IRS gave Curnutt commendations and multiple cash awards, each for about $1,000. It sent him around the country to conduct 64 training sessions so IRS auditors could learn how to efficiently spot these cheats. He also trained state tax auditors from California, Indiana, New Jersey and New York.

But the IRS never put Curnutt's insights into practice and never cracked down on the cheaters, allowing them to escape paying tens of billions of dollars in federal and state taxes.

Now Curnutt's mission in life, at age 76, is to get states and the IRS to go after these cheats.

Little to Fear

Cheating on your taxes carries little risk, despite the myth that legions of aggressive auditors and tax collectors hound taxpayers, a myth the IRS revives each spring when it noisily arrests a few notable people for tax evasion, knowing it will make the news. This strategy is known as general deterrence: Make a very public example of a few people to scare others into complying.

But Congress has cut and cut the IRS staff. Last year the IRS budget worked out to $33.55 per American, a 20 percent reduction compared with 2002, even though the number of taxpayers has grown 11 percent. Those cuts came as Congress enacted myriad laws making the tax code ever more complex and passed all sorts of social welfare legislation via tax code changes.

All that means there are fewer audits of both people and corporations. And most examinations of tax returns are so superficial that a few IRS agents deride them as audit lite. Here's one indication of how little you have to fear: Last year, couples and individuals filed more than 144 million tax returns, and fewer than 1,000 people went to prison, all of them for egregious misconduct. Judges are getting tougher, though. Half of those prison sentences last year were for 15 months or more, compared with just four months in the 1990s.

Another reason to relax: The Justice Department, which handles tax prosecutions, never indicts someone over a single tax return. You have to repeat the same or similar tax offenses to get in front of a grand jury.

Besides, if you are a wage earner, Congress has enacted laws that make cheating almost impossible, in large part because the government takes its taxes out of your paycheck before you get your money. In contrast, it trusts investors and business owners to self-report their income, which creates multiple opportunities to cheat, as I have been documenting for years in my articles and books like Perfectly Legal, and as the United States taxpayer advocate has pointed out in reports to Congress.

Given that background, the tax-cheat ploy Curnutt uncovered is remarkably easy. On Form 1065, the one partnerships file, just leave Line 10 on Schedule K blank, or report a smaller figure than the real one.

Why does that one line go unnoticed when the IRS selects tax returns for audit? IRS software scans only for what it is told to look for. (Think of those Star Trek episodes in which the Enterprise scans a planet for life, detects none and then discovers life forms the scanners were not tuned to notice.)

This week, news broke that the IRS effectively fails to audit massive partnerships, like hedge funds and private equity funds, even though corporations of the same size are under constant IRS audit. A short video, "Tax Analysts Video Examines Audit-Proof Businesses," explains how partnerships escape audits.

Figuring out what number should be on Line 10 can be a complex challenge, one that Curnutt trained all those auditors to figure out. The problem is that the IRS is still not flagging partnership returns with a blank Line 10 or a dubious figure. That means none of them are delivered to auditors. And Curnutt discovered that the IRS needs to check Line 10 only for the year when property with big debts is disposed of, typically 20 years after purchase.

This is not a huge group of returns, but it does represent a big chunk of unpaid taxes. At best, only one in 400 partnerships returns gets audited, because partnerships do not pay taxes—they only pass money on to investors who, in turn, pay any taxes due from partnership profits on their own tax returns. Curnutt's research shows that cheating occurs among a small minority of the million real estate partnership returns filed each year. And they are not those for the big partners with hundreds or thousands of investors, but mostly groups of three to six people who all know each other. Curnutt figured this out by using software to sift through the haystack of complicated tax returns to find the nettlesome few.

No Authority to Audit

Curnutt has been unable to get the IRS to follow up on the insights for which it honored him, for reasons neither spokespeople nor IRS commissioners have explained, despite my repeated queries. So Curnutt began offering his services to every state with an income tax. The response has been underwhelming.

Years ago, a Kentucky tax official told me Curnutt was rebuffed because his audits would have exposed some of the then-governor's major campaign donors. New York state officials under four governors have repeatedly claimed, in writing and interviews, that they already do "Curnutt audits," but that is not true.

California's Franchise Tax Board told Curnutt in 2009 that it could not afford to hire him. His fee? Travel expenses, plus $140 an hour. That is a fraction of the hourly rate states routinely pay lawyers, accountants and other experts for advice that does not raise a penny of revenue. And Curnutt could put many millions into state coffers for minimal expense and effort.

Only one state hired Curnutt: Pennsylvania. From 2002 to 2009, he put in seven months of work there and found hundreds of real estate partnerships that had failed to report more than $1.6 billion in income. That works out to close to $50 million in unpaid state taxes, and $400 million in federal taxes. Curnutt's fee came to less than $200,000.

Pennsylvania hired Curnutt when Ed Rendell, a progressive Democrat, was governor. Tom Corbett, an anti-tax Republican, took office in 2011, and the state told Curnutt his services were no longer required.

Several tax authorities have told me over the years to be wary of Curnutt, saying he is just trying to make money because he doesn't have enough to get by. Curnutt lives in a modest home in Arlington, Texas, halfway between Dallas and Fort Worth, with his wife and a grown son paralyzed from the neck down because a madman shot him (and killed his boyhood friend) because they were being too noisy while playing.

Making money is not what drives Curnutt. He inherited vast farmland that others manage for him. What motivates him is what drives all good detectives: a burning desire to catch the bad guys. It infuriates Curnutt that he knows how to nail the cheats and nothing is being done.

If New York state hired him, Curnutt says, "there is only one possible outcome—all hell will break loose. But there is no way, short of a directive from Governor Andrew Cuomo, that the state Department of Taxation and Finance will allow me to" identify the tax cheats.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman's office wants to employ the Curnutt investigative techniques but lacks the authority to audit. The state comptroller, Thomas DiNapoli, has authority to look into tax filings, but emails from that office make it clear that, as Curnutt puts it, "they want to stay a mile away from this."

The New York tax agency has told Curnutt, state lawmakers and me that it already looks for the kind of cheating he describes, but a careful reading of its statements shows that it is describing a different and unrelated form of cheating, one likely to snare only non-New Yorkers.

Both the chief of the New York state tax tribunal and the chief clerk told me they had not heard of a case concerning the relevant federal tax code, Section 1231, in decades. State records show the last case was more than 30 years ago. Both also said they could not recall any cases about misreported gains by real estate partnerships, and none show up in a search of filings.

None show up because New York state is not looking for this kind of cheating. If it did, Curnutt calculates that it would bring in $200 million in tax money in bad years like 2009, and $700 million in the good years, like 2000 and 2007.

But New York clearly doesn't need the money to undo massive budget cuts to child care, fix potholes on state highways or ease the burdens of many millions of people who file honest tax returns.

Go Ahead! Cheat!

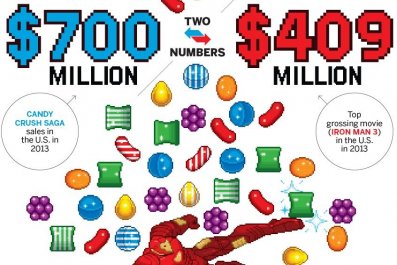

The odds for taxpayers overall, according to IRS data analyzed by Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse for 2013 and 1993, per million taxpayers:

2013 1993

13 20 Recommended for prosecution as a tax cheat

6.4 11 Indicted

4.2 8 Convicted

2.9 4 Sentenced to prison

0 0 Caught for "Curnutt cheating" in real estate partnerships.