"During wartime, people still dream, fall in love, aspire—they are human, they are not freaks."

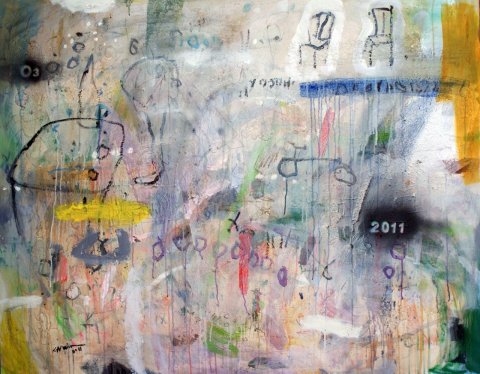

These are the words of Tamara Chalabi, scion of a well-known Iraqi family, who shepherded nearly a dozen Iraqi artists to Italy last year to show their work at the Venice Biennale art fair. The Iraqi pavilion was a hit, and the work is now on show in London.

Every conflict seems to produce a pivotal artist or work of art fueled by pain and suffering—from the poetry of Col John McCrae's "In Flanders Fields" to Anne Frank's Diary of a Young Girl and Pablo Picasso's Guernica.

More recently, there was Zlata Filipovic, who as a besieged Sarajevo schoolgirl kept a diary of her perceptions of war that was later published. And Ishmael Beah, a child soldier from Sierra Leone, wrote his harrowing memoir, A Long Way Gone, to draw attention to the plight of the more than 300,000 children forced into combat.

In Afghanistan, that artist was Khaled Hosseini. As a child, the author fled the Communist coup of Afghanistan in 1978 and the Soviet invasion of 1979. The Kite Runner and his two subsequent books put a human face on the turmoil in Afghanistan. Published over a period when the United States and its allies went to war in Hosseini's homeland, the books sold in more than 70 countries, and The Kite Runner was on the New York Times best-seller list for more than 100 weeks.

"In Afghanistan, so much of the music or poetry is about upheaval, losing homeland, suffering," Hosseini says. "Even the carpet makers will weave in image of refugees, orphans, camps."

Drawing on his experience as a refugee, he recently visited some of the 226,000 Syrian refugees in Arbil, Iraq, as part of his mandate as a good-will ambassador for the United Nations high commissioner for refugees (UNHCR).

Syria is in its fourth year of war and has more than 2.5 million refugees scattered over several countries. They will soon overtake Afghans as the world's largest refugee population.

Hosseini says the challenge is not so much to create art during wartime but rather to draw the public's attention to what inspired the work: the conflicts themselves and the civilian costs.

"The biggest challenge is getting people who are so far removed from this situation to understand what it is really like," Hosseini says. "I don't want my kids to think their world ends with their ZIP code."

Forced to flee his country as a child, he recalls, he felt helpless confronting the rebuilding of a life. "Being a refugee is a recalibration of who you are. You have to reposition yourself and realize that everything in your life that you had before is gone," he says.

"Whatever status you achieved is snatched from you," Hosseini adds, recalling "the moment when you realize you will never again return to your old life."

The former doctor, who rose at dawn to write The Kite Runner before his shifts at the hospital, and never thought it would be published, has come back to his hotel shaken from a day spent with a family who fled Aleppo.

"He's a 36-year-old father with four kids," he says. "He was a shoe salesman in his old life. Of course, he can't sell shoes now. They endured starvation and bombing and finally left when a bomb dropped on the fifth floor of their building—and they were trapped on the bottom floor."

Hosseini, who is now 49, points out that his experience as a refugee was vastly different. He did not live in a camp or a settlement or a tent when his parents fled Afghanistan. They went first to Paris, and later, "when we realized we could never go back," they flew to California.

Life in Silicon Valley was painfully isolating, and what the family suffered most from was a loss of identity. Hosseini's father, a former diplomat, became a driving instructor. "It was painful for him. He was an intellectual. He was 41 and had to go on welfare," says Hosseini. His mother, who had been the vice principal of a high school in Kabul, worked as a waitress at Denny's.

Hosseini spoke no English, and his new California high school was baffling. He later said he was not bullied but "worse: I was ignored."

In his case, that teenage angst was channeled into something vital. He went to medical school, became an internist and later, with his wife reading his early drafts, worked on his book.

"I do understand what it is like to be displaced," he says, "and at the risk of sounding highfalutin, it is always experiences like this that can kindle inspiration."

The conditions of the Syrian refugees in camps that Hosseini visited—Kawergosk and Darashakran—disturbed him. "I will never watch the news on Syria again and just see statistics," he says.

Neighboring countries that have taken in Syrian refugees, such as Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Egypt, have been generous, but the influx has inevitably put a strain on fragile economies and political infrastructures.

Iraq, which received a flood of refugees during last summer's tentative moment when intervention might have happened, is especially vulnerable, because the country is also in the midst of bloodshed.

Two years after U.S. troops left Iraq, violence has climbed back to its highest levels since the Sunni-Shi'ite bloodshed of 2006 and 2007, when tens of thousands of people were killed. In March 2014 alone, more than 1,000 people were killed, according the Iraq Body Count website, which tracks reported attacks.

Upcoming legislative elections in April are a major concern as an opportunity for more violence, and there have been weeks of fighting in Anbar province. The attacks are mainly by militias and armed groups, both Sunni and Shia. Baghdad is often the scene of the attacks, but the south and also the north, including Arbil, have witnessed bombings.

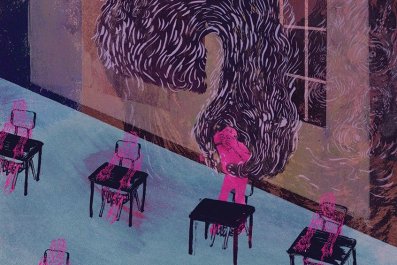

There is not much space for art or intellectual life when people fear going out, because getting caught in traffic might mean being blown up by a car bomb.

"It's all very rudimentary," says Chalabi, chairman of the Ruya Foundation for Contemporary Culture in Iraq who was behind the Venice Biennale exhibit Welcome to Iraq, which recently opened at SLG Gallery in London.

"There's hardly any materials for artists, very few art colleges," Chalabi says. "Those that exist are run by antiquated government curriculum. There's not much exchange between the artistic communities."

Despite all that, and despite logistical complications in getting visas, Chalabi says the artists were determined to make it to Venice.

"The drive to express yourself during times of war is huge," says Chalabi, whose father, Ahmad Chalabi, is a former deputy prime minister of Iraq. "They wanted and needed to do this work. These guys did not even go to art college. One of them works at the Ministry of Agriculture."

She explains how one team of artists—a duo called Wami—was overwhelmed by the "dirtiness of Basra."

"In their fantasy, Basra is the Venice of the East, so they created an entire house out of cardboard because the streets of Basra are full of trash," Chalabi says.

"We wanted to create an energy for them, so when they went back to Basra, to their homes, to their quiet lives, they feel they are part of a global art conversation. We want to keep it going. They don't have receptive audiences inside Iraq."

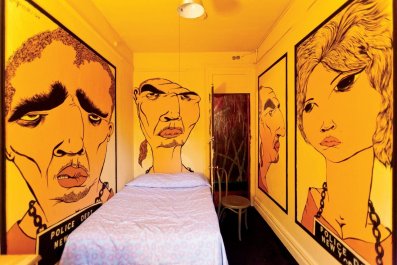

Another Iraqi artist, photographer Jamal Penjweny, decided to capture portraits of contemporary Iraqis holding up a photograph of Saddam Hussein covering their faces. In the Hussein years, the average Iraqi was subjected to a constant cult of Hussein—posters, statues, walls, TV. His image brought fear to a population, and even now, 11 years after his fall, people still remember that terror.

"His presence was so pervasive. We would hear his name several times a day," Penjweny remembers. "In our imagination, Saddam appeared profoundly evil, the reason for all our suffering."

The series, titled "Saddam Is Here," depicts the life that is still, in many ways, repressed and oppressive—this time not from a dictator but from violence. "Individual lives," he says, "are marked by seemingly never-ending conflict."

International curiosity about the reality of life inside Iraq led to the exhibit becoming one of the top five pavilions among the 88 in the Venice Biennale.

"It reflects the hunger the people have," Chalabi explains, "to connect with something that is not a bomb, not violent—that is really powerful. It's not like we changed the world, but we got a chance to tell a story."

Janine di Giovanni is the Middle East editor of Newsweek, as well as a consultant on the Syria crisis for UNHCR.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly named the author of the poem "In Flanders Fields."