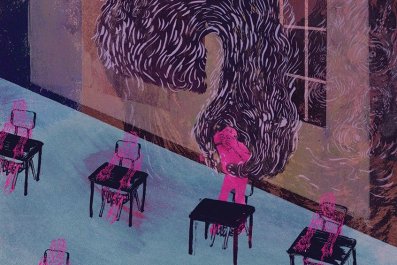

Edina, a Bosnian who lives near Srebrenica, was only 15 when she was captured along with a relative as they were foraging for food. Her family had fled to a forest. She was held for weeks and raped by five men. She says she survived because as it was happening, "I felt like I was someone else watching what was happening to me."

In the two decades since those events, Edina has tried to rebuild her life. Today, she is a mother, but she has the air of a broken woman. She sits on a bench in the Srebrenica Memorial and chats with visitors—including Angelina Jolie—with dulled emotions. Although Edina testified in The Hague in 2005, none of the men who raped her have been brought to justice. She says that her rapists walk free—and are living not far from where she now lives.

"I know who they are," she tells Newsweek. "I found them on the Internet on Facebook."

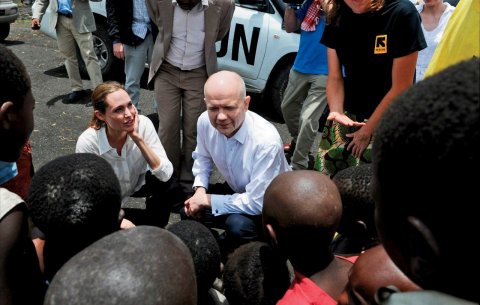

Jolie, the actress and director, has returned to Bosnia with British Foreign Secretary William Hague to promote their partnership directed at preventing sexual violence in conflict. Rape during wartime is often treated as a lesser war crime, and their initiative is an attempt to galvanize political will to uphold international standards of justice.

This means states must also acknowledge the suffering of the victims. Today, in this grim factory in Bosnia, they have come to meet the people who underwent such horror—and survived.

"These women—one of them told me she felt like she was sinking," says Jolie, dressed in black and wearing a head scarf to cover her hair. "They are so broken and yet so dignified.... They are such extraordinary women."

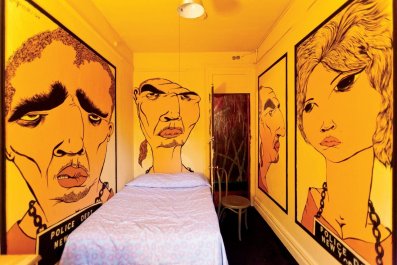

The concrete walls of the memorial, housed in a disused battery factory, are covered in photographs of the hazy days of July 1995, when more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys between the ages of 16 and 60 were ripped away from their families and massacred at the hands of Bosnian Serb forces.

In Bosnia, Jolie is something of a folk hero, and not for playing Lara Croft. In 2012, she made a powerful film about the country's rape camps, In the Land of Blood and Honey.

Jolie, the mother of six children and a special envoy for the United Nations high commissioner for refugees, filmed the movie in Bosnia, using actors from the former Yugoslavia, and immersed herself in the history of the region.

She read books, took notes, interviewed reporters who had covered the war and used authentic uniforms and radio scripts. When it came time for the premiere, she held it in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, in Zetra, the former Olympic skating arena and a place that was used during the siege to store food for the city's population.

She and Hague teamed up on a subject they are both passionately committed to after he watched Blood and Honey at the urging of his senior special adviser, Arminka Helic, a Bosnian who fled to the U.K. in 1992 to earn a Ph.D.

Hague was struck by the power of the film.

"I started this campaign with Angelina Jolie because foreign policy has got to be about more than just dealing with urgent crises—it has to be about improving the condition of humanity," says Hague.

Their campaign, called the Preventing Sexual Violence Initiative (PSVI), aims to end the shame that victims feel as well as the impunity that often follows such crimes, and to raise the awareness of the scale of rape during conflict.

In Rwanda, up to half a million people were raped during the genocide 20 years ago. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, which Jolie and Hague visited a year ago as part of their campaign, there have been an estimated 200,000 victims. In Syria today, there are thought to have been countless rapes, though the figures are hard to track because the taboo surrounding rape for Muslim women is so deep that many do not report it or even tell their husbands or family.

Between 1992 and 1995, an estimated 20,000 to 50,000 men, women and boys were raped in Bosnia, according to PSVI. Some of them were held in rape camps in areas such as Foca, Visegrad and Zenica, where they were abused up to a dozen times a day, by several rapists. The aim in some cases was to impregnate the women, to dilute the Muslim gene pool.

To this day, most of the men who committed such acts are free. Some survivors have talked of their desperation and humiliation when they had to face them in their hometowns. Others can never go home again, because of the stigma.

According to the British foreign office, there are seven ongoing sexual violence cases at the international court in The Hague involving 14 defendants, and, as of the end of 2013, another 35 cases were being handled by courts in Bosnia.

Still Missing

During the Bosnian war, Srebrenica was supposed to be a "safe haven" under the protection of United Nations forces. As General Ratko Mladic and his soldiers overran the town, women, children and unarmed men came to the factory that is now a memorial for protection. The U.N. peacekeepers there turned them out of their compound.

Some of the men were executed with a quick shot to the head—and they were the lucky ones. Others were forced into buildings, factories or fields, or hunted down in the forests like animals, where they were then machine-gunned in groups, their bodies falling into mass graves. Some survived but had to lie under dead bodies for hours until dark, when they could claw their way out, and escape.

"I have not had a day of joy since the day my father and twin brother were killed in the forest," says Hasan Hasanović, a survivor of the massacre who is escorting Jolie and Hague through the memorial. Hasanović was 19 at the time, and is only alive because he walked nearly 100 kilometers with other men to the free zone. Some made it out alive; others did not.

"Our biggest problem is how to recover," says Dubrovko Campara, a Bosnian prosecutor. "Everybody was hurt during that war.

"Once I asked one of the killers from Srebrenica what he remembered after he spent the day killing," Campara says quietly. "He told me, 'I was very tired after that day.'" Campara looks stricken. "They have remorse at the end, when they want their sentences reduced. But I am not sure they still understand how grave these crimes were."

Another source of torment for many women is the fact that the remains of their loved ones have still not been found. In October 1995, the Dayton Peace Accords effectively ended the war in Bosnia. One month before the accords were signed, Bosnian Serb forces, they would be caught and brought to international justice, unearthed some of the Srebrenica mass graves with bulldozers at night. They reburied the corpses elsewhere, believing this would cover their tracks when it came time for a war crimes investigation.

They also wanted "to erase history," says Kathryne Bomberger, the director general of the International Commission on Missing Persons, which was founded in 1998 with the purpose of tracking the remains of the survivors. "It is almost like saying: Their bones disappear, they disappear."

After meeting with victims, Jolie and Hague move to the cemetery, where white markers cover the remains of the more than 6,000 bodies found so far. The graves seem to go on forever. Every year on July 11, the families of the dead gather at the site and mourn. Some who recently found remains come to bury them. Jolie stands near a memorial that lists the names of the 8,000 victims, wiping tears from her eyes.

At the start of their visit, they spoke to a packed room of Bosnian army officers in Sarajevo. "At times, you may be all that stands between a child and violence that scars him or her forever," she told the soldiers. "Your actions may make the difference between a successful prosecution—or aggressors going unpunished."

Later, Jolie and Hague flew by helicopter over the mountains to Zenica, where they met more survivors at a small nongovernmental organization called Medica. Up a hilly street is a "safe house" for abused women, and a workshop for survivors to learn practical skills.

Sitting quietly waiting to talk is Lejla, who spent three years being held captive and raped, from the age of 14. At 17, she gave birth to a son. She says going home after she was released was difficult.

"Not everyone was happy to welcome me back home," she says, explaining how she has been afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder. "I had a small child with me, a child from a Serb. But also, I had been violated. People even made fun of me.

"I can't really tell you how I healed after it happened. I can't really explain the process of healing.... I had to learn everything all over again...how to laugh, how to put on makeup and to know that I am not to be blamed for what happened.

"I had to learn that I won't get anywhere by hating."

Lejla also testified in The Hague but felt frustrated by the process. "I don't think anyone in the court understands the victims," she says.

Not only do many rape victims see their attackers facing no consequences, but they themselves are marginalized by society. Many struggle even to make a living, says Nela Porobic, an academic who works with the women. "They often have no access to psychological counseling. They need financial security. Many can't even get their kids through school," she says.

In another room at the safe house sits Zihnija, 56. A former welder from Kakanj, he joined the Bosnian Army to defend his town at the beginning of the war. He was captured by Bosnian Serb forces shortly after the Dayton Peace Accords and incarcerated for 28 days. Because he was an officer, he says, he was given the worst treatment of all the prisoners, including being violated with a military shovel.

Zihnija believes the men who abused him, who left him bleeding on the floor, will never be brought to justice. But at the same time, he says, if they were sent to jail, "they probably have families and children—despite what they did, I don't want anyone's children to suffer."

Zihnija says he did tell his wife what happened to him, and eventually sought counseling. But the road to his recovery has been arduous. "I am a shell of a man," he says. At one point, describing what he lives with every day—flashbacks of the rape, images of the burning war that ravaged his country—he is on the verge of tears.

"Our faith teaches us to forgive," he says. "We can forgive. But we cannot erase our memories or the pain that we feel."

In June, Hague and Jolie will host a four-day summit in London that will bring together governments from 141 countries. Their goal is to promote practices that will standardize the investigation of large-scale sexual violence in wartime, working to raise awareness and train peacekeepers, police and the justice system.

"As foreign secretary of a powerful country, I feel that my country has to do something—because we can," Hague says. "And as a man, I feel a particular responsibility because these crimes are usually committed by men."