The three-page letter to Bernice King was a declaration of war. Again.

King—the chief executive of the nonprofit center named for her father, civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr.—had been running the institution for just 19 months, frantically trying to reverse years of deterioration in both its physical plant and reputation. But this bellicose letter threatened to destroy it all with what amounted to lawful extortion: If the center's board didn't force out Bernice King and two other directors, it would no longer be allowed to use the name, likeness or works of the martyred leader for any purpose. The King Center would not even be allowed to call itself the King Center. In essence, the institution founded by Bernice's mother, Coretta Scott King, would cease to exist.

What made the ultimatum last August all the more painful was that it came from two board members of the very nonprofit whose survival they were now threatening: Coretta's sons—Dexter King and Martin Luther King III. Bernice King's brothers.

Squabbles among the adult children of a famous patriarch are common, but the rancorous disputes of the King siblings—most of them over lucrative licensing deals for their father's words and image—are rending family ties and friendships forged during some of the most harrowing battles of the civil rights movement.

The suits, countersuits and accusations of unethical behavior and profiteering at first angered many of those closest to the family, who saw greed as the driving force. But after almost a decade of these internecine battles, some longtime friends are starting to wonder whether they are witnessing the tragic consequences of emotional damage inflicted on the siblings not only from their father's assassination but also from the murder of their grandmother. They also fear that bearing the heavy expectations of a world that hoped they'd pick up the mantle of a man revered as the apostle of nonviolence is crushing his children.

"We gave them pain but no fortune,'' says Andrew Young, the former United Nations ambassador who was with King when he was assassinated in 1968 and has been close to the siblings since they were children. "There have been enormous expectations put upon them, but almost no assistance. They have been living under a very difficult burden all of their lives, and still are."

Friends of the family are not surprised that there have been so many disputes about money, pushed in large part by Dexter, the youngest son. "I'm not a psychiatrist, but they have got to be so angry, they have got to be in so much pain, that when someone wants something from them, they feel someone should pay them for it,'' says Clarence Jones, Martin Luther King Jr.'s former personal lawyer and adviser, who in the past expressed rage at the siblings' behavior but who now believes it reflects deeper troubles.

Still, Jones says, he is not blind to the tragic impact of the siblings' actions. "It is so painful.... They might be fighting for the disposition of the King legacy, but most of it is really driven by money, money, money."

The 'Black Sheep'

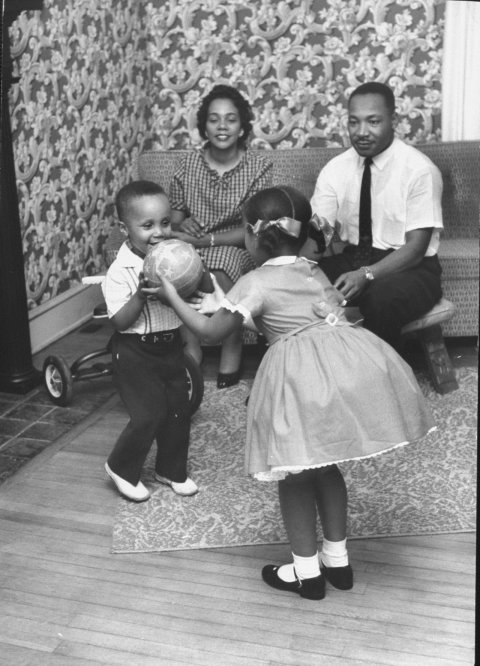

Martin Luther King Jr.'s four children didn't see their father much. While friends say he anguished over not being a stronger presence for his sons and daughters, King also believed that, as the moral leader of the civil rights movement, he had no choice but to make that sacrifice. Still, Yolanda, Martin, Dexter and Bernice loved their father and his exuberance, which they saw in his practical jokes, his willingness to roll around on the floor with them, and the delight he took in playing what they called "the refrigerator game," where he would have the children jump into his arms from the top of the refrigerator.

None of them fully comprehended what was happening around them. Like most families in the Vine City neighborhood of Atlanta, they had little money, and yet their father was always on television. Famous people like Jackie Robinson dropped by the house. When their father won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, Yolanda, the oldest, was just 9 years old, while her siblings were 7, 3 and almost 2; none of the children were quite sure what this award was.

On April 4, 1968, some of the children were watching television when their show was interrupted by a news flash: Their father had been shot in Memphis. More than an hour passed before word reached their home that he had died.

Shortly after her husband's assassination, Coretta decided to create a fitting memorial, an institution designed to perpetuate his legacy by addressing social issues. She called it the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center, and for more than a decade she ran it out of her basement. She raised money from wealthy philanthropists and helped assemble a board of prominent leaders, who soon changed the name of the Atlanta institution to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, better known as simply the King Center.

King left his family almost no money, but he did bequeath them one invaluable asset: his words. He had copyrighted his writings and his speeches—including his most famous, the "I Have a Dream" speech delivered in 1963 from the steps of Washington, D.C.'s Lincoln Memorial to 250,000 people. If anyone ever wanted to publish his writings or broadcast his speeches, they would have to pay the family for the rights.

The children were all able to go to college, thanks to the fund set up by longtime King friend and confidante Harry Belafonte. Yolanda attended Smith College, while Bernice went to Grinnell College before graduating from Spelman, a historically black college in Atlanta. The boys attended the alma mater of their father and grandfather, Morehouse College, a school exclusively for black men.

Dexter, the youngest, didn't really want to go to Morehouse. He says the University of Southern California offered him a football scholarship, and he had hoped to play in the NFL. But he felt duty-bound to continue the family tradition.

He struggled in college, though, and dropped out. By then, Dexter had come to see himself as a failure, and even referred to himself as the "black sheep" of the family. He had no interest in being a civil rights leader—he loved music and had run a successful deejay business while in college. He joined the Atlanta police, but that didn't last. After consulting a doctor, he learned he had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and began to believe that some of his difficulties stemmed from that condition.

As Dexter drifted, his siblings soared. Despite suffering from extreme shyness, his older brother Martin had a growing reputation as a community activist and was elected a county commissioner in Atlanta. Yolanda was a human rights activist, actress and director. Bernice felt called to preach like her father and even took the place of her mother to speak at the United Nations when she was 17.

By 1988, the King Center had a building adjacent to the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. and his father had preached. When the board pushed Coretta to name her successor, she called her children together to discuss the matter. Yolanda, Martin and Bernice couldn't take on the job—between acting, politics and preaching, all three had their hands full. That left only 27-year-old Dexter, who agreed to replace his mother at the King Center.

Board members balked—Dexter, they argued, was completely unqualified for the job—but eventually bowed to Coretta's wishes. Dexter began working as president of the King Center in April 1989, while his mother continued to serve as chief executive. But the directors never felt confident about him, and he was treated like a figurehead. A few months later, he resigned, angered at what he saw as the board's betrayal.

'I Have a Licensing Deal...'

By 1994, the onetime failure was seeing success. Pushed by his mother, Dexter again became president of the King Center. But by then, the institution's influence had waned, and the center was on the brink of bankruptcy. Professional executives wanted nothing to do with the place; instead, it was becoming Dexter's kingdom.

Having studied business at Morehouse, Dexter confidently attacked the financial problems. He declared that the center had never been a civil rights organization and slashed staff and programs. He purged the board that had snubbed him and pushed aside some of his father's longtime allies. And he began to create a new corporate ethos for the center.

But he was not only looking out for the center's interests. Dexter was also the primary force behind King Inc.—known formally as the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr. Inc. It held the rights to Dr. King's speeches, image and every other potentially valuable facet of his life. Dexter worked with a college chum, Philip Madison Jones, each of them controlling a third entity called Intellectual Properties Management Inc., the licensing dealmaker for the estate.

Gone were the days of lofty plans for social activism. Under Dexter's leadership, the King Center focused on economic activism. He leased his father's words and image, and spoke fondly of the commercial possibilities of the land surrounding the center. He planned to build a for-profit, interactive museum with holographic projections of his father delivering some of his most famous speeches.

While King Inc. was always on the lookout for organizations or businesses trying to inappropriately use the civil rights leader's image for commercial gain, it was willing, for a price, to let companies use it in questionable ways. For example, in 2001 the King estate licensed rights to Alcatel, a mobile phone company. The resulting advertisement was lambasted for its tackiness. It showed digitally doctored footage of Dr. King delivering the "I Have a Dream" speech, but without the cheering throngs; King appeared to be speaking to himself. Then a voice-over droned, "Before you can inspire, before you can touch, you must first connect. And the company that connects more of the world is Alcatel."

Even as financial troubles forced the King Center to lay off workers and mortgage King's birthplace, Dexter was receiving a hefty salary—$180,000 in 2003 alone. By then, he had been living in Los Angeles for three years, managing activities at the King Center mostly by telephone.

And his cash benefits didn't stop there. Under Dexter's leadership, the nonprofit King Center struck a deal that paid millions of dollars to Intellectual Properties Management Inc. Tax records show that in 2003, more than half of every dollar contributed to the King Center went to Intellectual Properties, although it is not clear how much of that was then used to pay the center's employees. Dexter was the chief executive of both entities.

Changing the Locks...Again

In the fall of 2003, visitors to Sotheby's were able to wander through the posh auction house and, after examining the latest art offerings, climb up to the 10th floor to ponder the thoughts and good works of a man who had dedicated his life to the poor and downtrodden. The papers, speeches and notes of Martin Luther King Jr. had been put up for auction by the estate, and Sotheby's was hoping to get at least $20 million for them.

This wasn't the first time someone had tried to put a price tag on these precious artifacts. In 1999, Congress came close to paying $20 million for the King papers in hopes of keeping them from a private buyer; if the arrangement had gone through, the documents would have been placed with the Library of Congress. But the deal fell apart when the estate declared that it would sell the documents but the family would retain all copyrights.

As the Sotheby's sale dragged on, it drew new attention to the King family—most of it negative. Facing the prospect of millions of dollars being pocketed by Dr. King's family while the center bearing his name languished in disrepair, newspapers and television commentators started a wail of condemnation.

Dexter, the primary target of this criticism, waved it off. "It seems the heirs of Martin Luther King Jr. are held to a higher standard—a higher standard of poverty," he wrote that year in his book, Growing Up King. "The truth may be that people don't want us, as the heirs, the estate, to benefit.... There are still forces out there that do not want what's best for our dad's legacy, or for my family to be in any way comfortable."

That rebuttal deftly ignored the fact that some of the people most appalled by the family's cash grab were those who had fought alongside Martin Luther King Jr. for so many years. They were flummoxed by what they called Dexter's obvious anger at his father and his resentment over the daunting expectations he had faced throughout his life. Friends of the family tried to convince Dexter that there was a difference between profiting and profiteering, and that having a million dollars—instead of tens of millions—did not constitute poverty.

Two months after Sotheby's put the papers up for auction, Dexter announced he was stepping down from the King Center to pursue media and entertainment projects. His brother, Martin Luther King III, would take his place as chief executive and president, while Coretta would return as acting board chair.

It quickly became apparent that this was a change in name only: Dexter became chief operating officer for the center and board chair. According to people close to the family, what ensued was backbiting and intrigue on a scale that rivaled any scandalous palace coup.

For almost two years after this, Dexter said he was "transitioning" out of the job, but in truth, he was blocking Martin from exercising any authority. While his older brother tried to run things day to day, Dexter worked the phones from his home in Malibu on almost a daily basis, calling the King Center to deliver instructions and demand information, although he rarely attended events sponsored by the facility. The joke among some employees was that the King Center was actually controlled by a tiny man who lived in a speakerphone.

In August 2005, Martin, Bernice and other directors met secretly with Coretta to put in place a consent decree that would depose Dexter as chairman. But before the plan could be finalized, Coretta suffered a debilitating stroke.

The board pressed on and named Martin the new chair. He then gathered the staff and told them they would be receiving their paychecks from the King Center instead of Intellectual Properties Management, which had received $4.2 million from the center since 2000 for its employee leasing deal and consulting. And then Martin changed all the locks on the King Center.

There was little doubt he faced an enormous challenge in fixing the King Center. The National Park Service said the facility needed more than $11.5 million in repairs. A reflecting pool surrounding the civil rights leader's tomb was leaking, as was the archive building that housed some of King's papers; electrical boxes were rusted and wires exposed; elevators did not meet building codes and drainage pipelines had collapsed.

But before any of those problems could be addressed, Dexter struck back. Hard. When he had assumed the chairmanship again in 2004, he pushed through a board resolution that granted him the power to appoint more than half a dozen new directors without seeking approval. In September, he flew from California to Atlanta. According to people with ties to the center, Dexter named six additional directors—all people close to him—and then used this new majority to reclaim the chairmanship. As a stunned employee looked on, Dexter arrived at the King Center, accompanied by police, and changed the locks yet again.

30 Pieces of Silver

At this point, the King Center was virtually nonfunctioning. A new board was in place, sort of. Dexter's siblings remained as directors, but none of them recognized the authority of the members who'd just been packed onto the board by their brother. Neither did Andrew Young, who had been with the center from the beginning. In response, Dexter established an executive committee of the board—made up of his allies—to run the center. He named his cousin, Isaac Farris, its new president.

In late December, the profiteering resumed. Ferris announced that the board was exploring a multimillion-dollar sale of King's birth home and several buildings in the center complex to the National Park Service.

This was too much for Martin III and Bernice, but they knew their voices on the board had been squelched by Dexter. Their only option, they decided, was to let the government know they hated this plan. On December 30, they held a press conference on the steps of the institution their mother had founded 36 years before.

"Bernice and I stand to differ with those who would sell our father's legacy and barter our mother's vision, whether it is for 30 pieces of silver or $30 million,'' Martin told reporters. No one who had read the New Testament could have missed that he was comparing Dexter and his allies to Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus.

Dexter was not moved, nor was he chastened. That same day, word circulated that he was looking to sell his father's papers and his mother's Vine City home.

Four weeks later, Coretta Scott King died.

The plans to sell the center buildings collapsed; without the support of the entire King family, officials at the National Park Service were unwilling to engage in any serious discussions. The attempt to auction off the King papers frightened prominent Atlanta citizens—Mayor Shirley Franklin pulled together a bid by the community. SunTrust Bank agreed to loan $32 million to the Community Foundation of Greater Atlanta, which would then purchase the documents from the King Center. Wealthy residents and corporations would then contribute money to the Community Foundation so it could repay the loan within two years. The title to the collection passed to Morehouse College, King's alma mater.

While the King Estate now had enormous cash reserves, only Dexter knew how the money was being handled. When his brother and sisters asked him to call a board meeting for King Inc., he ignored them. His siblings received no audited financials—they were simply being told to trust Dexter.

'Things Dr. King Preached Against'

Coretta had kept love letters beneath her bed, stored away in a blue Samsonite suitcase. In May 2008, Dexter struck a deal with a New York publisher that would allow the world to read his mother's private romantic writings to his father. The payday: $1.4 million.

The letters had been an important bit of leverage in an agreement with Penguin Group to publish what Dexter was calling his mother's autobiography. Years before, Coretta had met with a writer and had many hours of tape-recorded conversations, but in the end she decided she did not like the manuscript. But the recordings still existed, and the writer agreed to Dexter's request that she use them to revive the book project, while also incorporating details from the love letters.

But Bernice was the executor of their mother's estate, and she had the suitcase. Dexter called her, demanding that she turn over the documents, saying they were part of King Inc. and thus had to be given to him. Bernice put him off.

Then, on June 20, according to court records, Dexter or someone acting on his behalf at King Inc. accessed the accounts at Bank of America, where the money from Coretta's estate was held. A lot of the cash was taken.

Less than a month later, Bernice and Martin III sued Dexter and King Inc. in Superior Court of Fulton County, Ga. The lawsuit alleged that Dexter had removed money from his mother's estate account for his personal use. The brother and sister also went after Dexter's refusal to provide them with information about King Inc., in which they were shareholders. Without details, they accused him of having "wrongfully appropriated assets" of their father's estate for his own benefit.

Dexter countersued, claiming that his siblings had improperly used King Center office space and company cars. He also accused Bernice of corrupting their father's legacy by hosting a rally at the center against gay marriage.

A few months later, Dexter sued his siblings again, demanding that Bernice turn over the love letters so the "autobiography" of their mother could be published; without them, he said, the book deal with Penguin would be canceled. The letters were not part of a separate Coretta estate, Dexter maintained. These were documents written by Martin Luther King Jr.; they belonged to King Inc. and thus had to be turned over to Dexter for him to use as he would decide was best. Dexter claimed Coretta had indicated to him before she died that she wanted the letters published.

His siblings didn't believe that story.

Even the proposed writer, who would have been paid $200,000, grew queasy about the deal. She wanted to write something that the King children would approve of, not just add more grist to the litigation mill. "This fight is about control and money and materialism," she said of the dispute among the siblings. "These are the things that Dr. King preached against."

Friends of the King family grew increasingly frustrated as attempts to resolve the disputes went nowhere. Dexter would not listen, and many of his old allies began to describe him as "a bully." At one point, Andrew Young called Dexter for a discussion and found himself on the phone with both Dexter and Jones, his friend and business partner. For about an hour, Young says, he felt as if he was being tag-teamed by the two men as they relentlessly tried to wear him down.

"I just finally had to tell them to kiss my ass, and I hung up,'' Young says. "I called back later, apologized, but told them, 'I am not going to let you browbeat me.' ''

As the lawsuits dragged on, new financial dealings by King Inc. emerged, renewing criticism of the family. In 2009, media reports revealed that the estate had demanded and received $800,000 from the foundation spearheading the government's planned memorial to Dr. King on the Mall in Washington, D.C. The reason? Because the memorial would use Dr. King's image and words, and the estate owned the rights to those.

In October 2009, the litigation was finally resolved. No autobiography was published; as an outgrowth of the settlement, Stephen Rubino, a New Jersey lawyer who made his name pursuing sexual abuse cases on behalf of victims, was selected to replace Dexter as president and chief executive of King Inc. He assumed the job in March 2010. At the same time, Martin III took over the chairmanship of the estate and became the chief executive at the King Center. Dexter remained as chair of the King Center, but the directors he had packed onto the board were removed.

The King family squabbles died down for two years.

Bible for Sale

The first sign that trouble was returning came in January 2012, when Martin III announced he was resigning as chief executive. His reasons varied—he opposed what he said were plans to more closely ally the King Center with King Inc., and claimed he had been made into a figurehead with no authority. That same month, Bernice was named to take over the job. She received no salary.

At the end of 2012, Dexter's severance agreement with the King Center—which was paying him in excess of $150,000 annually—came to an end. A few months later, he approached Bernice, arguing that the center should name three co-chief executives: him, her and Martin. Bernice dismissed the idea as unworkable.

The King Center was busy in August 2013. The end of that month—August 28—would be the 50th anniversary of King's "I Have a Dream" speech and the March on Washington, and many events had been planned across the country in memory of the historic day.

The emailed letter from a lawyer for Dexter and Martin III went out on August 10. In it, Dexter revealed for the first time that, while serving as chairman of the King Center in 2007, he had signed a purported licensing deal with his sister Yolanda that turned over the rights to virtually every image and every word connected to their father at the King Center to King Inc. He claimed that even the name "King Center" belonged to King Inc. under the agreement. While the document says it served to only memorialize what was already understood, no one on the board had ever heard of such an arrangement.

Under the purported licensing deal, King Inc. could on its own accord terminate the King Center's right to use the words and images referenced in the arrangement—and the letter to the center's board proclaimed that King Inc. was doing just that. The reason? An "audit" had been conducted—when and how, no one at the King Center was sure—which showed that the facilities were in dilapidated condition, thereby putting the papers and memorabilia it held at risk.

The irony and chutzpah were staggering. Dexter had presided over the deterioration of the center. In his role as center chairman, he had purportedly signed away valuable rights held by the charitable group in exchange for nothing. And now, Dexter—who was still chairman of the center—was brandishing the document he had signed on its behalf as proof that the institution owed something to the for-profit group he ran. The conflicts of interest and potential violations of fiduciary duty were almost too numerous to detail.

But Dexter and Martin III—who now was allied with the brother he had so long opposed—offered the center a way out of annihilation. If it turned over all decision-making on the King intellectual property, placed Bernice on leave pending an investigation, and forced both Andrew Young and Alveda King-the siblings' cousin-off the board, King Inc. would not revoke the purported license secretly signed by Dexter so many years before.

Before the first lawsuit could be resolved, Dexter and Martin came in with another one in January: This time, they wanted Bernice to turn over the Nobel Peace Prize that had been won by their father, as well as his Bible, which had been used in the swearing in of President Barack Obama for his second term.

These were valuable assets of King Inc., the brothers argued, and could fetch a good price at sale.