How much does it tell you about a man if he cannot decide whether he wants to have a beard or not? What does it indicate if he appears clean shaven for a few days, then sports a stubble, then is clean shaven again, then appears with a full black beard till it vanishes again?

This is not a youngster hanging out with buddies or backpacking across America but instead a top member of India's leading political dynasty who is nearing his 44th birthday and is photographed and filmed every time he appears in public.

He is Rahul Gandhi, the 43-year-old heir apparent to the prime ministership of India—or so it seemed until it became apparent he did not want the job but then seemed to be working toward it, though he would never confirm his ultimate ambitions or intentions.

Confused? So are the people of India.

Although Gandhi is being promoted by his mother and lauded by supporters, Indian voters do not seem to want him, and he and the dynasty are facing a massive defeat when the results of a general election are announced in May.

The vanishing beard is significant. It illustrates the quandary that this obviously reluctant politician is in, in terms of what he is and what he wants to do, having been born into the dynasty that has headed India's Congress Party for all but nine years since the country's independence in 1947.

The party has been out of power for only about 13 of those years, and the family has provided three prime ministers: Jawaharlal Nehru, who led India into independence; his daughter, Indira Gandhi, who was shot by her Sikh security guards in 1984; and her son Rajiv, who was assassinated by a Sri Lankan Tamil suicide bomber in 1991. Adding to the family's tragedies, Rajiv's younger brother Sanjay, who played a leading role in Indira Gandhi's undemocratic and sometimes brutal 1975-77 state of emergency, died when a light plane he was piloting crashed in 1980.

The Nehru-Gandhi dynasty has remained at the top since Rajiv's death. After a few years in the shadows, his widow, Italian-born Sonia, became the chairperson of Congress in 1998 and led the party to election victories in 2004 and 2009. The daughter of a builder from northern Italy, she met Rajiv at a Cambridge, England, restaurant where she was working while studying at one of the city's language schools and had no interest in politics until after he died.

Now she is recognized as a top politician, although respect is tempered with wariness among Indians because she is a foreigner. In 2011 she was believed to have had a cancer operation at New York's Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, though the nature of her illness has not been confirmed.

For the past 10 years, she has headed India's United Progressive Alliance coalition, having cleverly handed the prime minister's job, at the head of the government, to an aging bureaucrat-economist-turned-politician, Manmohan Singh, now 81, who has failed to wield real power because of her dominance and the Machiavellian maneuverings of her courtiers and sycophants.

The government they headed became increasingly ineffective, plagued by corruption scandals and coalition problems. Economic growth plummeted from around 9 percent to under 5 percent. This has paved the way for Narendra Modi, a controversial and egotistical politician, to win what is becoming a presidential-style election at the head of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

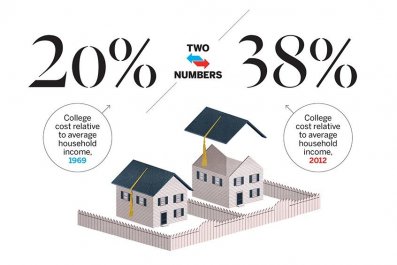

The Indian subcontinent is swamped with dynasties that have rarely contributed much to their country's well-being or development. More than a third of the Congress Party's members of parliament in the 2009 government came into politics through a family link, as did more than two-thirds of the MPs from all parties.

Political parties gain from dynasties because, as with film and sports stars, family candidates are instantly recognizable and so have less difficulty selling themselves in huge political arenas like India. Brand Gandhi generates instant recognition, and there is also the convenient association with Mahatma Gandhi, leader of India's independence campaign of peaceful protest, who was no relation.

Indira Gandhi, born a Nehru, married Feroze Gandhy who changed the spelling of his main name, thus giving the family an association with the stronger Mahatma brand, which still causes helpful confusion today. No one knows how many of the poor, who have instinctively voted for the Congress Party in past general elections, believe the Gandhis are descendants of the nation's founding father, but there must be many. (Foreigners who do not know India well also assume there are direct family links.)

{C}

This is the world in which Rahul Gandhi is trying to find his way. He has been unable to escape his legacy and has been put on a public pedestal that he would rather avoid. He has talked publicly about the trauma of assassination. At a Congress Party convention where he became the party's vice president in January last year, he explained how two of his grandmother's police security guards had taught him how to play badminton. "They were my friends. Then one day they killed my grandmother.... I felt pain like I had never felt before. My father was in Bengal, and he came back. The hospital was dark, green and dirty. There was a huge screaming crowd outside as I entered. It was the first time in my life that I saw my father crying. He was the bravest person I knew." Rahul was then 14.

His mother, Sonia, has seen herself as a dynastic bridge between her late husband and their son, just as Manmohan Singh has always said he would step aside as soon as Rahul decided to become prime minister. When he was first elected an MP in 2004, Rahul seemed to have some of the promise of his father, who was dragged into politics by his mother from a career as an airline pilot after Sanjay died. Though an inexperienced politician, Rajiv launched India on a path of long-term economic reforms in the 1980s.

Rahul Gandhi is good at mixing informally when he is on tour. "I come as a son and as a brother, and as a friend. Elections come and go, but I'll stay," he said while I was with him on the 2004 election trail in the family's traditional constituency of Amethi, a scruffy, underdeveloped town in the vast north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

He relaxed with crowds of desperately poor villagers, listening attentively, and they seemed to believe he cared and would help them. This was not just because he looked young and honest and sounded sincere, but because he looked and sounded like his father, who had been Amethi's MP.

For them, Rajiv had returned, 13 years after he was assassinated, and life might be good again. Like the villagers, I was struck by the similarities with his father. It wasn't just his looks—tallish, open-faced, good-looking, with short cropped hair and dressed in a traditional white kurta pajama that got crumpled as the day's heat wore on. It wasn't just that he spoke in the same quiet way, making brief remarks at election meetings because he had yet to master the rabble-rousing speeches that he now delivers. Like his father, he seemed to have the same passion to be of service to the country (a rare trait among modern politicians) and the same simple wish to try to help India change for the better.

{C}

Confirming that he was in politics for life, he told me, "What drives me in a big way is the need to tackle bigotry in India, bigotry that divides one caste and class from another.... I would like one day for everyone to perceive themselves as equal, not just upper castes seeing lower castes as equal but lower castes feeling that too.... I don't understand how we can talk about democracy when people don't see each other as equal."

That was 10 years ago, and he has not really progressed, though he has tried to reform some of the Congress Party's organization. The villagers in Amethi do not feel that he has stayed to help them. He is still their member of parliament, but he did little in the years after 2004, and his more astute and approachable sister, Priyanka, is now managing the constituency. He has spoken in similar terms in villages he has visited across the country, but he rarely if ever returns to check progress.

Rahul dropped in on the remote tribal people in the hills of Orissa, in eastern India; they were threatened by a bauxite mining project, and he promised to support their case. The project was stopped, but not because of his visit. A year later, he jumped on a motorbike at 3:30 one morning and rode to Delhi's satellite city of Greater Noida to join villagers in a "sit-in" protest against real estate land acquisition. There, he got some of his facts wrong and was briefly arrested, but achieved nothing.

He has never married, though there have been girlfriends, and for years he has frequently disappeared from public view—sometimes, it is believed, with friends in India, often abroad and always shrouded in secrecy. He has failed to lead his party to victory in state election campaigns and shirked taking a top job until last year, when he became the party vice president.

Since then, he has applied himself more consistently to politics, but he continues to refuse to acknowledge that he will be prime minister if the Congress Party were to confound the forecasters and opinion polls and win the election. His face is the most prominent on the party's election manifesto, though, significantly, Sonia stepped in to lead at the manifesto launch's press conference to add more strength to the party's message than Rahul would have been able to do, even though he has been leading the election campaign.

In the past year, Rahul has been airing all the right ideas about the changes that India needs, but he does not add nuts and bolts of policy to give his words credibility. His aim, he said in a recent TV interview (his first since 2004), was to change the way the political system was structured, end rule by dynasties, introduce real democracy in the Congress Party, empower women and the young, punish the corrupt and build an internationally significant manufacturing industry.

No one could write a better shopping list. But Rahul failed to add substance. When pushed by the TV interviewer, he merely repeated the list.

He has indicated before that he wants to end dynastic rule. This logically means he could be the last in the Nehru Gandhi dynasty's line, though he has never spelled that out. He has, however, woken up too late to save his party from what looks like a crushing defeat.

John Elliott's book Implosion: India's Tryst With Reality has just been published by HarperCollins India.