Banking as we know it is starting to look more outdated than a dot-matrix printer.

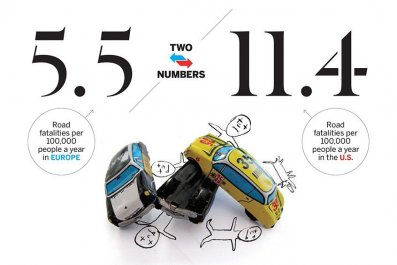

In China, consumers are rushing to give their savings to Internet companies instead of banks. In the Philippines, an emerging middle class is paying for school and health care using money from a new breed of social-network lenders. In the U.S., one-third of surveyed millennials say they expect to rely on tech-based financial services instead of banks, while 71 percent say they "would rather go to the dentist than listen to what banks are saying."

I guess they haven't met my dentist.

Greg McBride, senior analyst at Bankrate.com, was recently quoted as saying, "Call me old-fashioned, but if you're going to build wealth and save and invest for the future, you need to be part of the traditional financial system." These days, that sentiment comes off like your father telling you not to have sex before marriage.

Banks are basically just data—lots of financial data. They've worked hard to depopulate their branches, so banks aren't a physical thing to many of their customers. Money is mostly code flying around networks. The chief competitive advantage for banks today is the regulations that keep interlopers at bay.

But even regulations can't shelter banks much longer. The old concept of banking is getting attacked on all sides by new-generation companies that are smarter about data and use it in more imaginative ways. For years, banks have been considered ripe for disruption, and now we're starting to see how it can happen.

"Disruption" can get flung around by the tech community with all the restraint Louis C.K. applies to four-letter words that rhyme with luck. Usually, the techies apply the disruption label to some catastrophic failure brought on by the Internet, the way digital music blew up CDs. But banks may be in for a different experience. They might get disrupted the way a house gets disrupted by termites slowly eating through several support beams at the same time.

Lenddo looks like one such termite. It's an American venture-backed company operating in Asia, using data for banking in ways banks would never traditionally consider. Lenddo's insight: Data about who you know on social networks and what those people say about you is more accurate than a credit score in determining if you'll repay a loan.

"For hundreds of years, lending was based on reputation," Lenddo CEO Jeff Stewart told me. "Social networks allow us to go back to the basics of lending, but now at a global industrial scale." So far, Lenddo operates only in the Philippines, Mexico and Colombia. Those places have an emerging middle class, and those people often don't have financial histories that would qualify them for a loan from a bank. Lenddo is making loans based on social reputation, snatching an upcoming generation of customers from banks.

Lenddo doesn't lend in the U.S. because of the morass of regulations here. "We were live in the Philippines and issuing loans for less cost than just getting an opinion on how to do that in the state of New York," Stewart said. Still, in our hyper-connected world, finance is global. If Lenddo and companies like it succeed in the developing world, you think it won't wash up on U.S. or European shores? Of course it will.

In China, tech companies are setting another precedent. Less than a year ago, Alibaba, which has hundreds of millions of e-commerce customers, offered to pay consumers higher interest rates than China's banks. By February, 81 million people had signed up, and Alibaba now manages the nation's biggest money market fund. Recently, Baidu, China's top search company, applied for a banking license.

Why would an Internet company get into banking? Data! Power goes to the company that knows more about its users. Banking vacuums in tanker-loads of data about users—the money they have, the ways they use it, the things they buy. And all those times that people open the banking app to check on their money provides more data and more ways to market to customers. Behind the scenes, Google and Facebook executives have to be watching Alibaba and Baidu and dreaming of becoming the next Mr. Drysdale or George Bailey or whatever banker pops into their heads after watching Me-TV.

In the U.S., even with all the regulations, banks are dealing with new entities gnawing at their edges. Six years after the subprime financial crisis, major banks still fear lending to any but the most credit-worthy small businesses, leaving a huge swath of potential customers unable to get traditional loans. That has created an opening for a new kind of lender, such as Dealstruck, which uses the Internet to match wealthy people to small-business owners who need to borrow in order to grow. These tech-based alternative lenders have been springing up faster than weed shops in Colorado.

On top of all this, there's bitcoin. Either bitcoin or some other global digital transaction system will catch fire within the next few years. It will be to credit cards what Skype was to the long-distance telephone industry. By creating a cheaper, better way to pay for stuff, digital transactions will lure in banks' credit card customers—and siphon off vital bank revenue.

As new players offer more innovative ways to handle money, banks certainly won't be rescued by their relationships with consumers. We don't know our bank tellers or branch managers any better than we know the toll collectors on the turnpike. Online, they just offer us non-differentiated products, take our fees and do us the favor of not letting our money get stolen or lost.

No wonder millennials don't give a hoot about banks. The three-year survey by Scratch—which found that tidbit about preferring the dentist to listening to banks—concluded that this young generation born between 1981 and 2000 will drive "seismic" changes in banking.

Even consulting firm Accenture says the future doesn't look pretty for banks. "Thirty-five percent of banks' market share in North America could be up for grabs by 2020," says an Accenture report, which adds that 15 percent of traditional banks' revenue could shift to technology players.

Major banks, with all their operating costs, couldn't take such damage. Big structures only need to lose a beam or two to teeter before crashing to the ground.