You can see the air in Tehran—a faintly acrid orange haze that obscures the towering mountains that ring the sprawling metropolis. The white marble facades of the city's soaring cement buildings are covered with a thick layer of gray soot. Walking around the city center, women, children and the elderly can often be seen wearing facemasks, or clutching veils across their faces. In this smog, blinking stings the eyes; breathing burns the throat. And in the mornings, when the air is particularly bad, the sidewalks are empty.

But the traffic—a mass of 3 million cars gridlocked and spitting out toxic exhaust—grinds on.

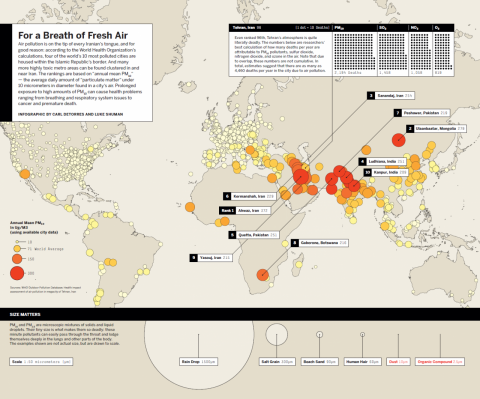

According to the latest World Health Organization numbers, four of the 10 worst-polluted cities in the world are in Iran. The number one slot was awarded to the small Iranian industrial city of Ahvaz, which has three times the concentration of pollutants as Beijing. Tehran, though not in the top 10 polluted cities overall, checks in at number 82 (of 1099), with roughly four times the concentration of polluting particles as smog-blighted Los Angeles. It's also the country's capital and the largest city in western Asia, a metropolis of over 8 million people with an outsized political influence in the region and a growing global presence.

When asked how the pollution in the country came to be this bad, many Iranian citizens and government officials point to U.S.-led trade sanctions that cut off access to the country's much-needed motor gasoline imports, and the technology needed to effectively produce home-grown gas. The sanctions, they say, have forced Iran to use outdated equipment and produce toxic formulations of cheap petroleum just to keep the country's 21 million cars from running on empty.

But some experts say the problem is more complicated, and the blame should be shared. They argue that the sanctions, though problematic, merely took the lid off of festering issues that had been building for many decades: a drastic population increase, mismanagement and—in some cases—corruption.

The air pollution crisis is now pervasive. "It's the single worst problem people in the city have to deal with, day in and day out," says a Tehran cab driver who had been complaining about the high pollution levels that day. "We can't not talk about it."

During bad periods, school is cancelled for a week at a time; the sick and elderly are told not to leave their homes; and people are banned from driving their cars on designated days of the week.

And people are dying from what they inhale. In 2013, the Health Ministry announced that up to 4,460 Tehran residents died due to air pollution, equivalent to roughly 25 percent of the total number of deaths in the city each year.

Debates over the city's growing air pollution woes have intensified—and there has even been talk of relocating the capital, in part to get away from the lethal pollution. In 2013, a parliamentary proposal to choose another capital city received 110 yeas from the 214 Chamber-members present for the vote; supporters of the change cited the pollution, debilitating traffic jams and high earthquake risks. Such a move would be incredibly costly, so it's unlikely to happen, but the fact that it is being seriously considered shows that many Iranians finally realize they are in the midst of an environmental disaster.

Lethal Gasoline

It's easy to blame the United States for that orange haze. On July 1, 2010, President Obama signed an amendment to the 1996 Iran Sanctions Act that imposed penalties on foreign entities for selling refined gasoline to the country. The sanctions were a response to the country's growing nuclear program; the White House hoped they would force then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to halt the country's nuclear programs.

At the time, restricting gasoline was seen as the best way to put pressure on Iran. Despite its thriving exports of crude oil, in 2010 Iran was dependent on imports for roughly 40 percent of its gasoline. It was the sixth biggest importer of fuel in the world, just behind the U.S. The new sanctions restricted the sale of gasoline to Iran, as well as any equipment or services that would aid the country in developing its own refining processes.

Initially, Ahmadinejad dismissed the sanctions as "futile," claiming that, "within a week we will reach the phase of self-sufficiency in producing petrol." But immediately after the new sanctions were signed, gasoline deliveries to Iran dropped from roughly 120,000 barrels a day to 30,000 barrels a day. Iran was suddenly gasping for gas.

At the time the sanctions went into place, Reza (a retired engineer who asked that Newsweek not use his real name out of concern for his privacy) was working in the petrochemical industry—which makes plastics, industrial chemicals and other goods out of crude oil. He says that the sanctions led directly to the production of a dangerous new form of gasoline. Throughout the country, the list of possible alternatives to imported gasoline was short, and time was running out. Iran's limited number of oil refineries tried to figure out how to produce more gasoline, but without outside help, they couldn't do much. Instead, they decided to bump up their gasoline's octane number by mixing in benzene, a byproduct from the petrochemical refining process that is known for being great at burning for fuel—but is also a highly toxic carcinogen.

"When you don't have what you need, you do what you have to do," says Reza. "But no one should be mixing benzene with gasoline."

While no one knows for certain how much benzene made it into Iran's gas, research has made it clear that much of it is highly toxic. The head of the Iranian parliamentary committee for health care claimed that Iranian petroleum at one point contained 10 times the level of contaminants of imported fuel, and environmental investigators found that diesel gas sold in Tehran showed roughly 800 times the international standard for sulfur.

The Grim Harvest

These days, Hamid Kashani lives in Virginia, but he spent most of his life in Tehran. Last summer, he returned to the Iranian capital after a three-year absence to manage his telecommunications business. "The air pollution had gotten much worse," Kashani tells Newsweek. "After just a few days, my hands and feet began swelling unbearably, and I began having problems breathing."

Kashani's doctor also found that his blood pressure was elevated, and started prescribing him higher and higher doses of medications. But nothing would alleviate the swelling or bring his blood pressure down. His doctor told him his problems were caused by Tehran's air and eventually warned him not to leave the house when pollution reached dangerous levels; Kashani says that for most of his time Tehran, this turned out to be four to five days each week. As his breathing began to get worse and staying in Tehran increasingly seemed a lethal choice, Kashani left his business half-finished and returned to Virginia, where his blood pressure has since stabilized.

Kaveh Madani, a lecturer in environmental management at Imperial College London, says his uncle's friend recently died of an asthma attack one particularly polluted day in Tehran when he made the fatal mistake of leaving the house without his inhaler. "By the time he came home to get it, he passed while his wife was bringing it to him," Madani tells Newsweek.

And last December, prominent Iranian film director Dariush Mehrjui criticized the government after his sister, award-winning film art director Jila Mehrjui, died prematurely of heart disease. "One thing that makes me furious is the cause of her death," Mehrjui said at her funeral. "This air pollution is killing everybody; all of my friends are suffering from cancer. Where is the head of our Department of Environment?"

Taken individually, the long list of health issues—from less serious afflictions like headaches and nosebleeds all the way up to life-threatening issues like heart attacks and lung disease—can't be definitively traced back to a single environmental cause. But in large-scale epidemiological studies of Tehran, the ties between increased health problems and the growing air pollution are becoming painfully clear.

Pollution has been directly linked to 11.6 percent more hospital emergency room visits every year, and to the rising rates of acute asthma, heart disease, lung cancer, and more. It's estimated that roughly 35 percent of children in Tehran have developed asthma or allergies as a result of man-made air pollutants.

In 2012, Masud Yunesian, a professor of epidemiology at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, conducted a study on mortality rates in Tehran. Yunesian took information gathered at the city's 25 air pollution monitoring stations, and—using a mathematical model designed by the World Health Organization—made his best estimate of how many lives could have been saved if the air in Tehran met internationally accepted standards of "healthy."

His study showed that roughly 2,200 deaths occurred as a result of exposure to PM10, a class of particles smaller than 10 microns in diameter produced as a byproduct of car emissions. PM10 particles are dangerous precisely because their small size allows them to travel deeper into the lungs than particles found in nature. The World Health Organizationsays these particles are a prime contributor to the high cancer rates found in the world's most-polluted cities, like Tehran.

There is no escaping the bad air. In Tehran, the number of "healthy" days—when levels of pollution measured at all of the city's 25 monitoring stations fall under the maximum concentrations—are exceedingly rare. By late February, according to the governor of the province of Tehran, the city has had only four "healthy" days in the year to that date.

And the worst days can be deadly. According to Yunesian, when there is a rise in air pollution, one or two days later there is a rise in the number of deaths city-wide. "Usually the elderly and those that already have chronic conditions are the most sensitive," he says. This is the so-called "harvesting effect," a phenomenon also seen in heat waves and cold spells, where the elderly, the young, and the ill are pushed to the brink by extreme environmental circumstances.

The High Cost of Clean Air

Protecting the environment is written into Iran's constitution: "The preservation of the environment, in which the present as well as the future generations have a right to flourishing social existence, is regarded as a public duty in the Islamic republic. Economic and other activities that inevitably involve pollution of the environment or cause irreparable damage to it are therefore forbidden." That remains the government's official line.

The reality, many environmental policy experts believe, is that years of poor governmental oversight have created a ruined—and increasingly dangerous—cityscape. "The [2010] sanctions basically took the veil off the catastrophic mismanagement that had already been going on," says Sam Khosravi, a former journalist and environmental consultant, who lived in Tehran for 30 years and is currently working toward a Ph.D. in natural resources management in the Netherlands. The real problem, says Khosravi, goes back to issues of regulation that stretch back decades further than the sanctions.

"Why were we relying so heavily on gasoline imports in the first place?" he says. "Why is there a monopoly of domestic cars, with not enough monitoring of quality? Why have annual smog checks been changed to happen every five years?"

According to Madani, Iran has purposely ignored long-term measures—such as protection of the environment—in favor of short-term development and political stability. In a city like Tehran with booming overpopulation, that means "build bigger, put more infrastructure in place—without really caring about the environmental side of it," he says. "The Iranian government is a crisis manager by necessity. You see a problem, you try to fix it. But it's reactive versus proactive."

Tehran's biggest problem goes back to cars. The city can safely accommodate 700,000 vehicles, according to researchers—but currently has more 3 million congesting its streets, producing nearly 75 percent of Tehran's air pollution. Of these, more than a million are over 20 years old and don't meet fuel-emission standards. Particularly when run on gas like the benzene-contaminated fuel produced after the sanctions, these cars are a prime source of those toxic particulates.

Many argue that the government needs to be doing more to get old cars off the road. And policies like exorbitantly high importation taxes on nondomestic vehicles only serve to create monopolies back at home, with no incentives to raise the industry standards for vehicle emissions.

"This is not an issue of today. We're really happy to sell our oil and get easy revenue, but we didn't build any infrastructure," a researcher in Iranian environmental policy who asked not to be named told Newsweek. "I'm not saying the sanctions have no impact, but they function as catalyzers. Add corruption to that, and add an extremely ineffective and mismanaged Environmental Protection Organization (EPO) with very little jurisdictional power, and you will get the result Iran has."

From an environmental planning perspective, the current crisis also has everything to do with Iran's international status, which suffered huge losses in the last eight years. "The political relations of Iran have an effect on this situation. You plan differently when you're friends with the rest of the world," Madani says.

But under its new administration, Iran is beginning to open up to the global community—which also means tackling its regulatory issues back home. New President Hassan Rouhani has already appointed scientist, journalist and environmental activist Massoumeh Ebtekar as the head of the state's EPO. Ebtekar previously held the position before Ahmadinejad's presidency, and she has been vocal about her belief that the government under Ahmadinejad blatantly ignored the country's escalating environmental issues. "The problem of pollution would have been resolvable with proper planning," she said in an interview at the beginning of March. "All of these efforts were disrupted eight years ago."

Ahmadinejad's government didn't just create poor top-down management of environmental policies; the lack of transparency during his presidency had a trickle-down effect that created a culture of distrust and, as a result, little progress at the grassroots level. "There used to be a lot of environmental groups working on these issues," says Khosravi. "In the last eight years these were totally discredited because Ahmadinejad characterized them as outsiders, and therefore untrustworthy."

Change may be long coming in Iran; in 2013, the country was ranked 144 out of 177 in perceived corruption by Transparency International. But at the very least, the new leadership, including Ebtekar, continues to say all the right things, and seems committed to repositioning the country as a responsible global citizen.

The Air Quality Control Company of Tehran has come up with a new slogan for the city—"Tehran: a City With Healthy Air at 2020"—and a recent announcement by the head of the National Iranian Oil Products Distribution Company claimed that only "clean" petroleum would be sold at the pump starting in mid-February.

In addition, Ebtekar, perhaps drawing on her strong activist ties, has made it clear that educating citizens via nongovernmental organizations is going to be a necessary part of Iran's new era of environmental responsibility.

In January, the U.S. and the E.U. enacted modest sanctions relief in exchange for Iran's suspension of its most sensitive nuclear program activities. Soon after, Ebtekar announced that the country could reinstate the importation of standard equipment like catalytic converters for car manufacturing, necessary for reducing emissions of harmful gases into the air.

After years of running unchecked, the auto industry has, in Ebtekar's words, "been warned" that the government is "geared up to take serious action." By this coming spring, the EPO will implement the—albeit still modest—2005 Euro 4 standards for vehicle emissions. (Euro 6 will be rolled out this year across the European continent.)

Lethal air pollution has already been dumped on Iran over decades of neglect and lack of governmental transparency. But it appears a cultural shift may finally be taking place: There are even plans under way for a national hybrid car project.