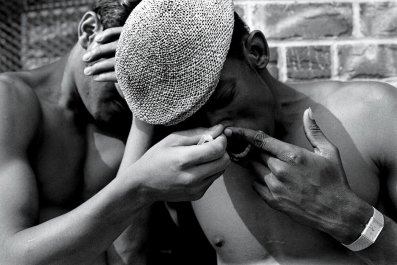

Gone is the familiar canary-yellow blazer, his plumage as chief executive officer of the Fiesta Bowl. In its stead, John Junker sports a royal-blue apron as he moves from table to table at the Society of St. Vincent de Paul charitable dining room in central Phoenix.

It is the breakfast hour, 7 a.m. In his hands, Junker, now the operations manager at the shelter, totes a red broom and dust bucket as he sweeps in and around the room's 23 circular tables. Occasionally, he stops to accept handshakes with volunteers, middle-aged men predominantly, who still regard him as a Valley of the Sun colossus, the community pillar whom Sports Illustrated dubbed "the seventh most powerful person in college football" in 2003.

John Junker, 58, was once the highest-paid college football bowl official in the country, drawing a salary of more than $600,000. He now earns $47,000 annually while helping to feed the homeless. He is still in the hospitality business. "Saint John" is how a few of his former Fiesta Bowl associates disparagingly refer to their defrocked boss.

On March 13, 2012, Junker, who had been the sultan of the Fiesta Bowl since 1990, pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court to a single federal felony conspiracy charge for his role in an illegal campaign-finance scheme. On Thursday, U.S. District Judge David Campbell sentenced him to eight months in federal prison. Legally, Junker is guilty of coercing 11 employees at the Fiesta Bowl to donate money to various political campaigns and then reimbursing them from the Fiesta Bowl coffers. Symbolically, Junker, who used the eight-figure endowment of the Fiesta Bowl, technically a nonprofit, as a means to belong to four private golf clubs in three states and drew a non-salaried allowance of approximately $1,300 per day for approximately 10 years, became the face of hubris and corruption that sports media and the public had long suspected was rampant in the stacked-deck ecosystem of the Bowl Championship Series (BCS).

In November 2009, Craig Harris, a business reporter at The Arizona Republic, exposed Junker's campaign financing subterfuge in a front-page story, and in March 2011, a Special Committee formed by the Fiesta Bowl produced a scathing 276-page report detailing his myriad abuses of power. The list is far too long to enumerate here, but includes $95,000 for a round of golf with Jack Nicklaus (Junker did not play); $33,000 for Junker's 50th birthday gala in Pebble Beach, Calif.; $13,000 for airfare and other considerations for the wedding of his executive assistant, Kelly Keogh; and $1,241 for a visit to Bourbon Street Circus, a high-end Phoenix strip club, in 2008.

There has long been a choirboy/Caligula dichotomy with Junker. The fifth of eight children, Junker, who declined to be interviewed for this story, is a 1973 graduate of Gerard Catholic High School in Phoenix. In his youth, he played the organ during Sunday Mass at a hospital for the mentally impaired. He graduated from Arizona State University in 1977 and went to work for the Fiesta Bowl in 1980.

Over the next three decades, Junker, the Fiesta Bowl and Phoenix would all scale unforeseen heights on the national sports landscape. Once a sleepy Christmas Day afterthought played at a one-tiered stadium in Tempe, Ariz., the Fiesta Bowl hosted its first de facto national championship on January 2, 1987. It has since hosted six more national championship games and is now one of the four bowls in the BCS rotation. No single person was more responsible for this than the charming, self-effacing and extroverted Junker.

In 1960, when Junker was 4, Phoenix was not among the top 20 largest metropolitan areas in the United States and was home to no major sports teams. Today, it ranks sixth in size, with four major professional sports franchises.

In 1980, Junker, then 24, joined the Fiesta Bowl staff and quickly learned the art of socializing with players, coaches and media. Three decades later, he was earning north of $600,000 per year, and the Fiesta Bowl, with dozens of staffers and hundreds of year-round volunteers, was his fiefdom. At some point along the way, Junker stopped working for the Fiesta Bowl and the Fiesta Bowl started working for him.

"John Junker was earning $600,000 a year," says Dan Wetzel, who along with Josh Peter and Jeff Passan wrote a book excoriating the cynicism and corruption in the BCS, "and yet he had a $2,500-a-month automobile allowance. What was he driving—a Manhattan townhouse?"

Junker has paid $62,500 in restitution to the Fiesta Bowl, but his hubris and dishonesty have left a debt that may be impossible to repay in a lifetime. And why Junker has never been indicted for his numerous documented misuses of Fiesta Bowl funds is a stickier question. "That's the million-dollar question," says Harris, who along with others suggests that the state of Arizona may not be prepared to grapple with all the cockroaches that would scurry out once that floorboard was lifted.

In 2011, Junker went to work at the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, where he had been a volunteer the previous decade. In his first year there, according to his attorney, Stephen Dichter, he put in 1,500 to 2,000 hours, exclusively on a volunteer basis. In 2012 Junker was put on the full-time staff. His wife, Susan, was also put on the paid staff, as a development officer. "John has turned down several raises since he started working there," Dichter says. "We felt that it was important to do that, with him serving his...penance."

The John Junker who feeds the homeless and avoids eye contact with people he once called friends seems to be the epitome of the humble servant. He looks like a changed and contrite man as he sweeps up after the shelter's breakfast service, but not everyone is convinced that sufficient penance has been done, nor have all the lessons here been learned. "John Junker?" asks Wetzel, whose book with Peter and Passan is titled Death to the BCS: The Definitive Case Against the Bowl Championship Series. "When we printed our updated edition, we dedicated the second book to Junker for proving the first book correct."