There is the Philadelphia you know and the Philadelphia you will never see. The first summons a cornucopia of familiar images: Benjamin Franklin, Rocky Balboa, cheesesteaks whiz wit. The second is safely out of view from the cobblestone streets of Society Hill or the brewpubs of Northern Liberties. But if you wander north on Broad Street, well past the alabaster phallus of City Hall, you may glimpse the first hints of that obscure Philadelphia in the emptied husk of the Divine Lorraine Hotel, a sullied spinster with more than a century of stories but nobody to hear them anymore.

Shortly thereafter start the Badlands, North Philadelphia neighborhoods like Kensington, whose row-house lanes were once home to working-class whites whose modestly prosperous lives were circumscribed by the factory, the church, the union hall, the front stoop and the bar. On a summer Sunday, a trip to Connie Mack Stadium or an outing to the Jersey Shore. Then cue the familiar midcentury forces: minority influx, white flight, factories moving to China, crack, crack babies, the end of welfare as we know it, here at the end of the land, the Philadelphia you will never know.

I drove through the Badlands with Barbara Laker and Wendy Ruderman, two journalists for the Philadelphia Daily News who shared a 2010 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting and are the authors of Busted: A Tale of Corruption and Betrayal in the City of Brotherly Love. The book is based on a newspaper series, "Tainted Justice," that revealed such an astounding degree of corruption among Philadelphia's drug cops that you would not quite believe it in a Martin Scorsese movie. But your belief, or lack thereof, is irrelevant, because this story is true.

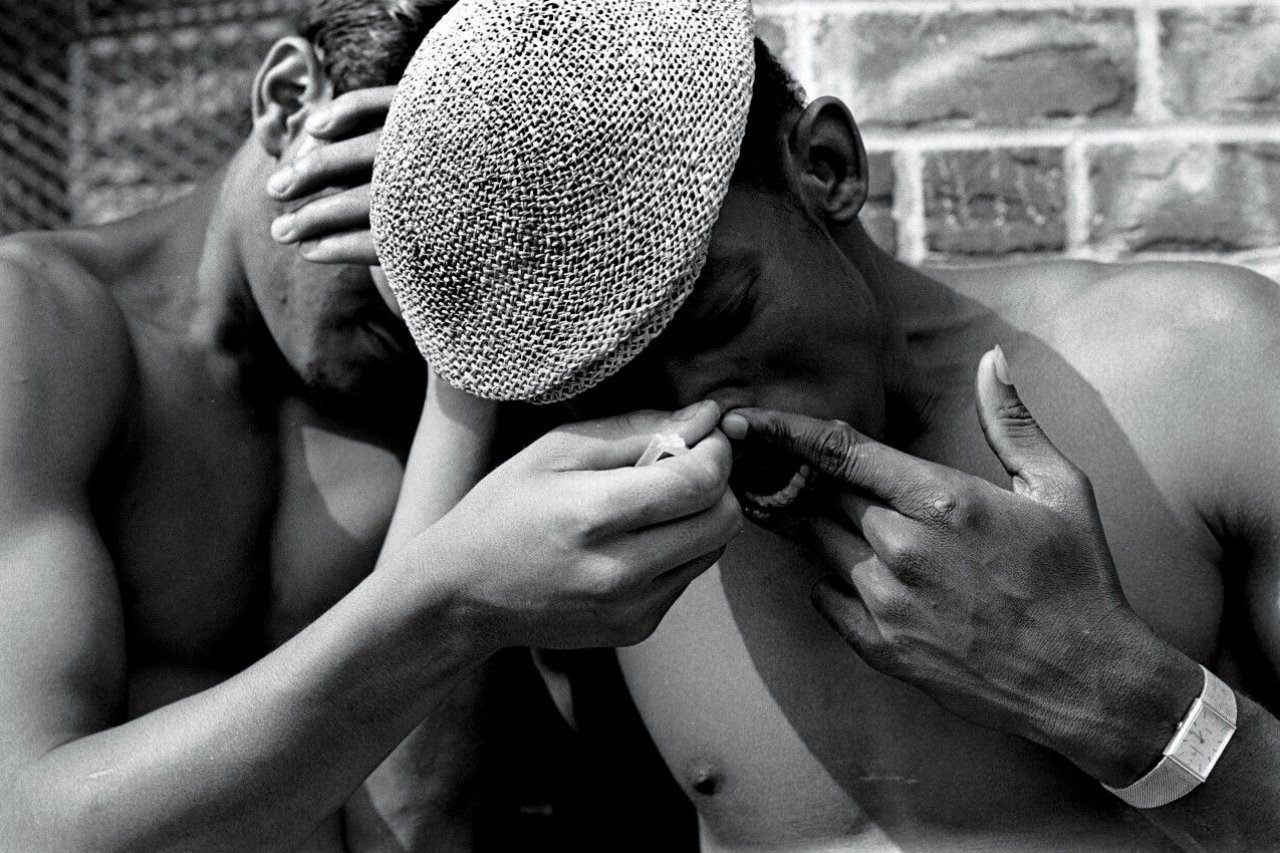

It was the depths of February when Laker and Ruderman took me into the Badlands. No amount of snow could turn this into a Currier and Ives scene, but winter hid what could be hidden, driving all manner of urban ills indoors. National Geographic Channel recently called these streets "one of the largest open-air drug markets in the eastern United States." Legions of young men lingered on street corners, doing nothing while obviously doing something. A car pulled into a narrow street and someone dashed toward an opened window with heroin or crack. The drug trade was the only living thing here amidst the dead factories and empty lots where waste peeked through snow like the buds of early spring.

Busted is a very good book about very bad people, a great read about great injustice. I would love to say that it is a story of redemption, but honesty interdicts. The crooked narcotic cops whom Laker and Ruderman exposed have not been stripped of their badges (yet), though several have been assigned to desk duty. The owners of the convenience stores these cops raided have received no restitution. The women whom one of these cops routinely sexually assaulted during house raids remain victims unavenged, though at least no longer cowering in helpless silence. And the Badlands are as bad as they've ever been.

The hero here is journalism, and those of us insane or stubborn enough to remain on the deck of a ship we are routinely told is about to plummet to the depths. By journalism, I do not mean cat listicles, "think pieces" about Instagrammed sunsets, or whatever else may pass for meretricious click-bait, but the near-forgotten practice of walking the streets, paper and pad in hand, talking to people, and then writing about it, not because you want a Gawker link (and let me be forthright: I'd love a Gawker link) but because there are stories that demand to be told. Ruderman and Laker told such a story, lifting out of obscurity the lives of others while imperiling their own.

Philadelphia has a proud history of civic corruption, which Ruderman surmises is because "the unions control everything. They make it difficult to get things done. And they were very protective of these cops." Whatever the source of Philly's culture of malfeasance, it had certainly touched the men and women in blue. The Philadelphia Police Department had so long courted dysfunction that a city district attorney lamented in the 1990s, "When the police are indistinguishable from the bad guys, then society has a serious problem."

But when narcotics unit informant Benny Martinez showed up the offices of the Philadelphia Daily News in the late fall of 2008, Philadelphia had experienced several murders of police officers, and goodwill for cops was consequently running high. Moreover, Benny had brought his story to "The People Paper" (note the populist exile of the possessive), the tabloid universally preferred by cops and their families in northeast Philadelphia over the stodgier Philadelphia Inquirer. Soon enough, that very same newspaper would be vilified, Laker and Ruderman branded "Slime Sistas" with no supposed purpose but to shame the very people who kept the city safe. As one reader informed them during the steady drip of "Tainted Justice," "It is people like you who are to blame for the unprecedented violence against the Philadelphia Police."

What Laker and Ruderman uncovered would not prove flattering to the department, plagued as it was by a "recurring cancer" of a police force that too often acted like a rapacious cartel. At first, what they had on their hands seemed to involve little more than a too-tangled relationship between Benny ("Confidential Informant 103") and narcotics cop Jeffrey Cujdik, one that started fruitfully in about 2003, but had more recently devolved into the two men working in concert to fake warrants, which would lead to raids based on nonexistent evidence. A successful raid netted the drug-addled Benny as much as $250, so he didn't care much for evidentiary propriety. In 2008, the two had a falling-out after Cujdik decided to boot Benny from a house he had rented to him. Playing the role of landlord to your drug-case informant is well outside the rules. But even then, Cujdik's transgressions would not have merited much more than a few column inches in the Metro section and, perhaps, an outraged editorial if it was a slow day.

Yet the cancer was deeper. As Laker and Ruderman continued to publish their "Tainted Justice" stories, a lawyer contacted the two reporters with a far more disconcerting revelation: Cujdik's squad was raiding convenience stores around Philadelphia under the pretense that bodegas run by hardworking immigrants were facilitating the drug trade by selling plastic baggies that would subsequently be used for packaging narcotics. The raids, though, served as shameless pretense to steal money and goods. Bursting into a store like a SWAT team, the cops proceeded to disable security cameras. And then the fun began, as the two women write in Busted:

When the cameras went dark, the cops stole thousands of dollars in cash and pillaged the stores, guzzling energy drinks and scarfing down Cheez-Its and Little Debbie fudge brownies. They inhaled bags of sunflower seeds, spitting the salty shells on the floor, and helped themselves to fresh turkey hoagies, not bothering to close the refrigerated deli case, leaving the meat and cheese to spoil. They left deep fryers filled with hot vegetable oil simmering on high, not caring if the store burned to the ground. Hopped up on power, the cops swiped the shelves bare, carting off brown boxes filled with cigarettes, batteries, and canned goods. A Hispanic woman who worked at a Dominican-owned store put it simply: "It was like they was shopping."

Nor was this the worst of the cops' transgressions. That ignominious distinction belongs to an officer named Tom Tolstoy, better known by his revealing nickname: The Boob Man. Infamous for fondling women during drug raids, he preyed on buxom Latinas, who, he figured, had neither the clout nor wherewithal to make the kind of complaint that might stick. Laker and Ruderman managed to track down several victims, including one woman who was digitally penetrated by Tolstoy during one of these raids, which never quite led to the Scarface-sized stashes such shows of force might have suggested. Incredibly, Tolstoy not only remains in the employ of the Philadelphia Police Department, but hopes to open a criminal-justice themed charter school.

Laker and Ruderman did not do all this at their desks: They don't give Pulitzers for aggregation, at least not yet. "I love crack houses," Laker told me. She knew that the reason Cujdik's squad could raid houses, harass women and steal from stores with impunity is because while the arrival of a wine bar near Rittenhouse Square may elicit gallons of ink, the depredations of the Badlands are so endemic, they no longer pass for news. Still, Laker would rather be in Kensington, talking to the downtrodden, than writing about how Philadelphia is the new Brooklyn. "It's a privilege that I get to go into these neighborhoods," she says, "and talk to people who aren't of my world."

Blonde and slim, Laker does not look like the sort of woman who passes easily through North Philadelphia without notice. "Man, I'm in, like, f***ing bimboland," the profanity-prone Ruderman recalls thinking when she first came to work with Laker from the Inquirer. For that matter, the petite Ruderman does not exactly look like an extra from The Wire, either, her incessant f-bombs notwithstanding. Maybe that was why the junkies, dealers, prostitutes and pimps of the Badlands talked to them - many times. "I don't think we come across as intimidating," Laker says, while Ruderman flatly told me that a reporter who looked like I do (white, male) would have had a much harder time getting access.

Not that these two had it easy. The backdrop of Busted is the protracted decline of print journalism, which in Philadelphia seemed to spell imminent doom for both the Inquirer and the Daily News (which are owned by the same entity). "A confidential informant in the city of Philadelphia is one step above a Daily News reporter," croaked police union chief John McNesby, who continues to this day to defend the disgraced cops.

When Ruderman and Laker won their improbable Pulitzer, they did so for a newspaper that was in bankruptcy. Today, the Daily News and Inquirer share a bright newsroom in the cast-iron Strawbridge & Clothier building. With its model race cars, sleek steel furniture and lime walls, the space looks like something out of Silicon Valley, not the lovably cluttered newsroom in The Paper. And one floor is enough, for severe Inquirer layoffs have taken their toll. Meanwhile, the Art Deco tower that once housed both papers sits empty. The newspaper industry's declining fortunes stem, the women surmise in Busted, from our having "trained a whole generation of readers to get their news for free on the Internet while drinking $4 lattes."

Nevertheless, it's hard to imagine two reporters more committed to the ink-stained art, which they insist on perfecting at the workaday tabloid that is the Daily News. (Ruderman briefly worked for The New York Times in 2012, but returned to Philadelphia after a year.) They persist even as the profession takes an obvious toll on their personal lives. The woman known around the newsroom as "Mama Laker" was already divorced by the late aughts; in the course of Busted, she goes on a series of dreary dates that hardly seem more pleasant than an afternoon in a drug den. Ruderman, meanwhile, had two young kids to raise: This is surely the only true-crime book in which the words "I want boob" are uttered outside a strip club. That her marriage eventually dissolved is a disheartening but not surprising revelation. It comes along with a warning from Laker: "Women really can have it all - just not at the same time."

A cynic might say that the Pulitzer is little more than self-congratulation for a dying industry. And that may be the case. I don't really know, and neither do the doomsayers. But the notion of reporting the news thrills me today as much as it did back in high school, when I would phone home to beg for permission to stay in the office past midnight, for the latest issue of Hall Highlights had yet to be put to bed, and what was a European history quiz compared to the truth we were preparing to unleash? Ruderman and Laker know better than anyone this ink-stained anguish that sustains us. Busted is proof that journalism still lives, still matters.