It was one of the biggest heists in history, fleecing half-a-billion dollars from people around the globe, and almost no one—except a small group of thieves, their confederates and the white-hat computer sleuths chasing them through cyberspace—knew it was taking place.

In January, federal investigators announced that Aleksandr Andreevich Panin, a Russian national who was the mastermind behind the crimes, had pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit fraud. Panin's capture was far more than just another tale of a crook who found illicit riches online. His case reveals many alarming details of a lawless underground flourishing in the darkest corners of the Internet, where hackers peddle off-the-shelf software that, for as little as a few thousand dollars, allows even the most unsophisticated computer novice to start emptying the bank accounts of people they've never met, or even seen.

No longer does someone bent on Internet crime have to dedicate weeks to writing code and testing programs, or even have the basic knowledge required to do so. Anyone can become an expert thief in a matter of minutes by using programs sold through hacker websites. The illegal programs—known as malware toolkits or crimeware—have their own brand names, like ZeuS, SpyEye and the Butterfly Bot.

The evolution of these programs presents a complex challenge for law enforcement as the range of wrongdoers has dramatically expanded, increasing both the number of perpetrators and the ease with which they can commit fraud. Malware toolkits "have created an all-new type of hacker,'' says Timothy Ryan, a former cybercrime specialist at the Federal Bureau of Investigation who is now a managing director of cyber investigations at Kroll, a private security company. "Whenever you have a proliferation of these weapons, it just means that the bar to entering cybercrime is a lot lower."

The amount of money being looted through malware toolkits is eye-popping. For example, a single criminal—known online as Soldier—stole about $17,000 a day with SpyEye, raking in approximately $3.2 million in the first half of 2011, according to one report. Soldier appeared to have targeted three banks—Chase, Wells Fargo and Bank of America—and infected the computers of about 3,500 online customers.

To hide their proceeds, these cyber-criminals often lure others to help—sometimes unknowingly. Soldier, for example, sent checks through an accomplice in West Hollywood, Calif., who went by the name Viatcheslav, investigators say. Those funds were then moved to a second co-conspirator in Los Angeles known as Gabriella. In a move common to malware thieves, the cash was then sent either by wire or courier to a group of people known as money mules or smurfers who think they have been recruited to work as receivables clerks or payment processing agents for a legitimate business. But in truth, the job is a fake one and the company fictitious—instead, the mules are just the last step in a money-laundering chain in which they deposit checks in their own accounts, and then wire the money to another bank under the control of the hacker. For what they believe is the processing of revenue from legitimate transactions, the mules are paid a percentage of the total amount of cash moved.

Soldier's fictitious company for money mules was called L&O Consulting LLC. Millions of dollars ran through these mules, although some potential "employees" figured out it was a scam before taking the job. For example, one prospect called out the fraud to a supposed personnel manager at L&O in a July 11, 2011 email obtained by investigator. "Form [sic] the job description, I can be 99.99% certain it's a money laundering scheme," the prospective employee wrote.

Others, however, fell for L&O's pitch and became unwitting accomplices in the scam, only to find out too late that their new "job" was a lie. "I started to work for you and got a bad check,'' one of the money mules wrote in an email to a supposed manager at L&O. "Now my accounts are locked up." This individual added that if someone didn't send him a good check, he would call the FBI and the Better Business Bureau. He never got that check.

'Legit Job Is Sucks'

There are so many people using this malware that criminal investigators have found that the best way to attack this threat is to treat the wrongdoing as a traditional "hub-and-spoke" conspiracy, and target the software developers and sellers of the programs, rather than just the users. That is why the arrest and guilty plea of Panin, the designer of SpyEye crimeware, is so important—despite the frequent online boasts by many toolkit makers that they can never be caught, this case shows that the government can track down even the most sophisticated of them.

The path that led to Panin's arrest began in 2009 at the offices of a computer security company called Trend Micro. Loucif Kharouni, senior threat researcher, was trolling hacker websites in search of new trends that might pose a danger to computer systems. He had heard from clients that new programs were compromising financial transactions and hoped to find some details in online hacker forums. There, he discovered someone offering to sell the malware toolkit first known as EYEBOT, but later changed to SpyEye.

This was a new one for Kharouni. He knew about ZeuS, crimeware that emerged around 2006 for stealing information such as login IDs and passwords from banking customers' online accounts. But SpyEye was different, with a broad array of attachable features. For example, it had a video plug-in that could be used to take snapshots of any infected computer's screen and code that could hide SpyEye on a flash drive, allowing it to spread every time the data storage device was plugged into a USB port.

Generally, SpyEye functioned the same way as other malware toolkits. The software is known as a backdoor Trojan Horse, or simple Trojan, and is downloaded onto the computers of unsuspecting people when they visit infected websites, open seemingly innocuous emails or click on a deceptive pop-up ad. The infected devices then become part of what is called a "botnet"—computers that can collectively be controlled by an outside hacker. In one method of data-grabbing, the keystrokes of users who are unknowingly part of the botnet are relayed back to what is known as a "command and control server" operated by the hacker.

Once a hacker gains control of a computer through SpyEye, the crimes then perpetrated through it can be almost undetectable. A computer user who logs in to an online bank account, for example, could be followed by SpyEye, which can create a wire transfer from that bank to another account controlled by the hacker. The bonus here for the thief: One feature of SpyEye makes sure that even after the money is moved, the online account does not show any decrease in funds available. A customer can only detect the theft by checking monthly statements or consulting with the bank.

To crack the secrets of SpyEye, Kharouni and his team at Trend Micro began targeting users and developers of the program, trying to discover the real identities behind the screen names and other digital identifiers. Quickly, Trend Micro deduced that there were a handful of large players in the SpyEye business—someone who went by names such as "Gribodemon" or "Harderman," and another called "Bx1." They also discovered a big-time SpyEye customer known as Soldier.

Gribodemon and Harderman were both Panin, the original designer of SpyEye. Hackers who had dealt with Panin said in online interviews with Newsweek that he originally told potential customers to contact him through ICQ, an instant messenger service, on which he had an account identified by the numbers 4571122. However, he quickly became sloppy, opening up an email account and signing up for a different messenger service that were both easily traceable to Russia, where he lived in the city of Tver.

Few if any of the hackers who did business with him knew his name, but Panin engaged in some stilted chitchat with his customers, another careless move for someone trying to keep his identity a secret.

For example, just after 8 a.m. on December 14, 2010, Panin was IMing with a hacker called gzero and revealed details about himself in response to repeated questions. There is no telling whether gzero was a government agent or an outside investigator trying to identify Panin, but gzero does appear to be a cyber-criminal—four months after the conversation, gzero offered 12,000 operating PayPal accounts for sale to the highest bidder on a hacker site, either a real crime or a sting set up to snare others.

According to a transcript of their conversation obtained by an industry researcher, gzero was aware that Panin, who was speaking as Gribodemon, had just returned from vacation. Panin at first sounded annoyed as gzero asked about his time off, grousing in broken English that he had lots of work to do. Gzero pressed ahead with questions.

"May I ask gribo," gzero typed.

Panin responded with a question mark.

"Do you do this AND a legit [job?]" gzero continued. "Or is it just malware development? I cannot imagine where you find the time if you also have a job. "

Panin's response again indicated that English isn't his first language. "Legit job is sucks," he wrote, adding soon after that his work entailed "just malware development."

Bx1—identified by prosecutors as Hamza Bendelladj—left clues about his identity around the Internet. In reviewing online evidence trails connected to hacker postings and texting addresses, Kharouni determined that Bx1 and Gribodemon (Panin) had begun working together on developing SpyEye. While Panin had first written the code for the malware toolkit, he began outsourcing portions of it for further development so he could focus on managing his growing business.

Tracking Bx1 was complicated; Kharouni and his team would have him under observation online for days, only to find that he had disappeared. Then he would emerge again, leaving new clues about his identity every so often. "So many of these guys get arrogant and think they will never make mistakes," Kharouni says. "So they end up being more open than they should and disclosing more information about themselves that can be used to identify them."

Someone using multiple servers to disguise their place of origin can be more easily found once an investigator knows their location, and information about a hacker's background is gravy. With Bx1, a key bit of information emerged because he was mad. On a hacker site, someone was challenging his knowledge about some inconsequential topic, and, in a response, Bx1 mentioned he was from Algeria, spoke French and lived in Morocco. Just crumbs of information, perhaps, but the kind of details that—if established as true—narrow down the scope of potential suspects.

Small Warlock Fools

After several months of work, Kharouni decided that his team had developed enough information about Gribodemon and Bx1 to call in the FBI. But Trend Micro did not stop its investigation; instead, the threat researchers continued tracking the cyber-criminals, feeding whatever details they learned to the government.

On June 29, 2010, Panin—using one of his pseudonyms—posted an advertisement on the hacker forum darkode.com, which he had joined six months earlier. In part, the posting read, "SpyEye - this is a bank Trojan with form grabbing possibility." In other words, Panin was offering malware designed to steal bank information. A few days later, Bx1 commented on the darkode forum, saying he had done business with the hacker advertising SpyEye and could vouch for him. Orders started coming in as investigators watched for months.

For Panin, July 6, 2011 probably seemed like any other day. An online customer approached him, expressing an interest in purchasing SpyEye. The two negotiated for a bit, and the customer agreed to pay $8,500 for the base program and some add-ons. The customer transmitted the money to an account designated by Panin at Liberty Reserve, an online digital currency service shut down last year amid allegations that it was connected to illegal activities. Panin then uploaded the SpyEye program to sendspace.com, a transmission service for large files. But this was far from a typical malware sale—the customer was an undercover law-enforcement agent.

Around this time, Panin's business was also under attack from the hacker world. Months before, a French hacker known to the online community as Xylitol rained havoc on Panin's SpyEye business. The young man, unemployed and living with his parents, had emerged as an important player in the piracy business by "cracking" copy protection technology built into most commercial software products. At some point, Xylitol decided to apply his skills to malware toolkits and cracked SpyEye, meaning that anyone could take a purchased version of the crimeware and copy it again and again. The French hacker was robbing the robbers.

When free versions of SpyEye appeared on hacker sites, Panin moved quickly, trying to update his product so that he could stay in business. He had every reason to think his plan could easily work. After all, Web browser companies were rapidly plugging up vulnerabilities in their code to block SpyEye, so each updated version of the crimeware included new ways to get around those advances in security. But soon after each updated version was introduced, Xylitol cracked it and put the latest SpyEye program on the Internet for anyone to take for free.

By the fall of 2011, Panin was tired of playing catch-up with Xylitol. He promised his customers that he was developing an all-new SpyEye, vowing it would have features that had never been available. Then, proclaiming he was heading off to write code, Panin disappeared from online. But December came and no new version of SpyEye appeared. Some customers tried to contact him, to no avail. He had shut down his IM account, and emails to anyone working with him on SpyEye went unanswered.

Rumors flew through the hacker world. Perhaps Panin—still known to his criminal compatriots as Gribodemon or Harderman—had died. Perhaps he had been arrested. No matter—hackers can be a skittish lot. When words like arrested are bandied about, they run. According to research conducted by Damballa, a computer network security firm based in Atlanta, Panin's large customers began dropping the toolkit and using others. Almost overnight that December, four of the leading SpyEye criminal operator groups—called Three Foot Convicts, Small Warlock Fools, East Sun Outfit and Jumbo Bunny Force—swapped out of Panin's program and began using a variant of ZeuS instead, according to Damballa.

A few months later, more bad news for Panin. On March 12, 2012, Microsoft emailed a summons to all of Panin's email addresses and suspected addresses notifying him that the company was suing. SpyEye had been designed to attack computers running Microsoft Windows operating systems, and the company was fighting back. The suit was filed against "John Does 1-39 et. al." Panin was John Doe number 3.

Panin's world was collapsing. A global network of law-enforcement agencies—including Britain's National Crime Agency, the National Police of the Netherlands, the Australian Federal Police, Interpol and an array of other public and private investigative groups—were working to determine his name, find him and then arrest him.

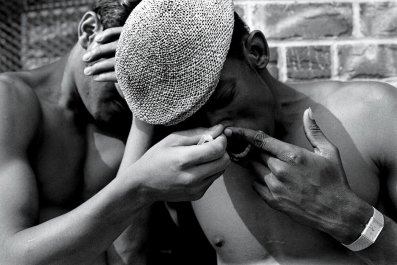

In January 2013, law enforcement learned that Bendelladj—the man identified by the FBI as Bx1—was planning to travel with his family from Malaysia to Egypt, with a stopover in Bangkok. Officials notified the Royal Thai Police Immigration Bureau that Bendelladj was a wanted man and was about to arrive at Suvarnabhumi Airport. Thai police officers boarded the plane as it sat on the tarmac and informed Bendelladj that he was under arrest. He was led off the plane, smiling broadly. During a subsequent press conference held by the police, Bendelladj grinned incessantly, leading some of the offices to nickname him "the happy hacker."

Thai law enforcement quickly arranged for Bendelladj to be transported to Atlanta, where federal charges were awaiting him. At the time of Bendelladj's arrest, prosecutors also obtained an indictment against Panin, although he was identified only as "John Doe a/k/a Gribodemon."

News of Bendelladj's arrest—as well as his identification as Bx1 by prosecutors—shot through hacker forums and was greeted with outrage. Some of his compatriots set up a "Free Hamza" Facebook site; about 2,400 people have signaled their support for him there. Support for him among hackers intensified in May after he pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Despite the widespread notice of the arrest—and the fact that Bendelladj had been picked up while traveling on vacation—Panin still seemed to believe he was invincible. He, too, decided to leave his home last summer for a trip, flying from Russia to the Dominican Republic. But unknown to Panin, Interpol had already circulated a "red notice" to its member nations about him - the closest thing to an international arrest warrant. So when Panin showed up in the Dominican Republic, which is part of Interpol, officials there knew he was a wanted man. After conferring with Interpol and the United States, officials with the Departamento Nacional de Investigaciones picked up Panin; at first, he was told there was an issue with his immigration papers. But a short time later, he was also on a plane to Atlanta, where he was jailed.

"They'll Never Stop"

By the time Panin pleaded guilty in January, the market for SpyEye had evaporated. But the cyber-criminals were far from finished looting bank accounts and stealing online identities. Instead of SpyEye, they had moved on malware with names like Ice IX, Citadel and Andromeda—less powerful programs, but ones that experts say are growing increasingly more sophisticated.

Panin may be gone, but the business he pushed to new heights with the most threatening malware ever developed won't likely go away. "They'll never stop," Kharouni says about the cyber-criminals and their malware toolkits. "It's a good market. And bad guys want to monetize a good market."