Suicide seems a quintessentially personal tragedy: a single person struggles with unique demons until it becomes too much. But it is also, in some cases, a national tragedy.

According to a recently published study, the former Soviet Union leads the world in suicide, with about 27.8 suicides per 100,000 people. By comparison, the most recent data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate about 38,000 Americans take their own life annually, or 12.4 per 100,000 people.

Equally startling is the gender gap in suicide rates in the post-Soviet countries. While men commit suicide at higher rates than women across the globe, the imbalance is staggering in the former Soviet Union. In Lithuania, for example, for every 100,000 people total, 61.3 men commit suicide while just 10.4 women kill themselves.

This is not a new trend; it can be traced back to December of 1991, when the USSR was officially dissolved. The male suicide rate in Eastern Europe surged during the early 1990s, as did drug and alcohol abuse, and has remained high. Life expectancy in post-Soviet states followed similar patterns: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Russian men live, on average, about 63 years, while Russian women have an average life expectancy of 75. In the U.S., the average life expectancy for men is 76, and for women, it's 81.

As a result, the demographic gender gap is stark in this part of the world. Old men are few and far between, while old women—clad in babushkas, carrying groceries, chatting with their friends on park benches—are highly visible. In spite (or perhaps because) of a culture in which women's rights continue to lag behind much of the Western World, it's women who have proven to be the resilient gender. Men in the post-Soviet era, meanwhile, have suffered tremendously during the geopolitical transitions of the past two decades.

"Literally their entire world got turned upside down, socioeconomically and psychologically," says Judy Twigg, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who specializes in health and demography in Russia. "It's not hard to understand how that would have been incredibly, gut-wrenchingly disruptive for this population."

When the Soviet Union dissolved, gender roles there also fell apart. In a 2009 study called "Social Suffering, Post-Soviet Masculinities and Working-Class Men," Arturas Tereskinas, a professor of sociology at the Vytautas Magnus University in Lithuania, explained that the concept of masculinity and "working-class heroes" that was so prominent a part of the Soviet ethos became "increasingly marginalized." High rates of unemployment and a new, emerging service economy that demanded communication skills—imagine an Apple store manned by surly drunks with no social graces—left many Russian men without jobs or prospects.

In part, this was because many Soviet men never developed the skills necessary to succeed in a postindustrial economy. Under Kremlin rule, trust was hard to come by, and men spent the majority of their time at work, with co-workers who were often guarded and suspicious. Women, on the other hand, were more able to cultivate a close network of friends they could rely on—what Twigg refers to as "kitchen table friends." As a result, their communication skills—and social coping strategies—were much more developed than those of men.

A 2003 study titled "The Gender Gap in Suicide and Premature Death or: Why Are Men So Vulnerable?" identified these "maladaptive coping strategies" as the reason Eastern European males became more prone to suicide. The study found that when faced with social change, these post-Soviet men were unwilling and unable to seek help or express emotion. Meanwhile, "women are able to express their pain publicly through the rhetoric of equal rights and gender justice," Tereskinas writes. "[The] 'inexpressive' male suffering is left unacknowledged and unaddressed."

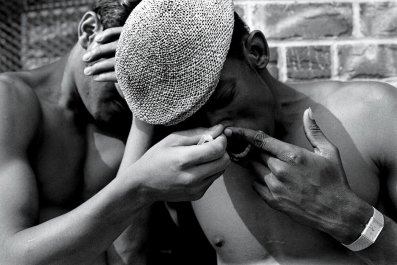

Many men, suffering silently, turned to booze; a 2012 study titled "The Intersection of Life Expectancy and Gender in a Transitional State: the Case of Russia" found that men in countries of the former Soviet Union dealt with the shame associated with the fall of the USSR through drinking and violence, rather than exposing their vulnerabilities.

In popular Russian culture it's commonplace to poke fun at the idea that Russian men are "useless," often too drunk to do anything. And media often portray "the woman [as] the stronger one, and the man is the one who's an appendage, and essentially useless," Twigg tells Newsweek. But the crude stereotype is all too real—Eastern European men are some of the heaviest drinkers in the world: the WHO states that Eastern Europeans consume 14.5 liters of pure alcohol per person, per year. By comparison, the average U.S. resident drinks only 9.6 liters per year.

And the drinking isn't just personal; it's political. Vodka was and continues to be a huge source of income for the region, Russia in particular. For years, the Kremlin even encouraged alcohol consumption in order to bring in more revenue for the government. "Those who drink, those who smoke," Aleksei L. Kudrin, Russia's finance minister said in 2010, "are doing more to help the state" by buying these products.

Monika Bonckute, a Lithuanian journalist at the newspaper Lietuvos Rytas, tells Newsweek that "drinking was a way to protest against dictatorship and express your despair of not having the freedom to build your own life. Binge-drinking was glorified in Soviet culture, and it still is in post-Soviet culture."

Consuming so much alcohol has serious public health consequences. In addition to the known long-term health impacts, a meta-analysis of almost 30 years of medical literature on the subject concluded that alcoholism increases the risk of suicide. Another recent study, "Distal Risk Factors for Suicidal Behavior in Alcoholics: Replications and New Findings," found that 40 percent of all patients seeking treatment for alcohol dependence reported at least one suicide attempt.

And because mental health treatment in Eastern Europe—including addiction therapy for alcohol abuse—is so far below global standards, even those who want help often can't get it. Under Soviet rule, and during the dissolution of the USSR, people struggling with depression or substance abuse did not have real options in mental health care. "The whole discipline of psychiatry and mental health care was an abomination in the Soviet period," says Twigg. Under Soviet rule, political dissidents were often thrown into psychiatric institutions, where they were drugged and tortured. "The whole discipline was perverted to the point where none of the Soviet institutions of psychiatry were even admitted to international scientific societies," says Twigg. "They're still years and years behind [the West]."

Of course, a poor mental health care system is going to affect both men and women. But when the men are already primed to take their problems to the local bar, the limited opportunities for help available to them will shrink further.

Bonckute, who grew up knowing many male alcoholics and almost no female alcoholics, is resigned to the notion that men in her home country and neighboring post-Soviet blocs will remain unable to ask for the help they need, and instead turn to the bottle, or worse. "Old habits die hard," she says, "and it's not so hard to find an excuse to despair in post-Soviet Lithuania."