The ubiquity of the common cold explains why science goes to a lot of trouble to find a cure. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has stated that scientists know more about the cold-causing rhinovirus than every other virus in existence, for example. They have detailed models of the virus that they can blow up on a computer screen and pore over to examine its intricate network of cliffs and canyons.

They may know a lot about the common cold, but they don't know the most important thing. A cure is not on the horizon, and it will be a waste of money to keep trying to find one.

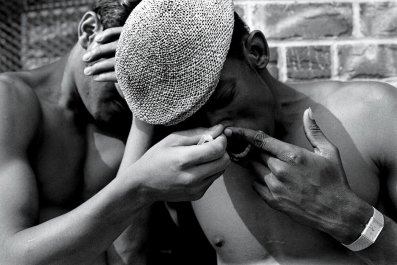

If you're a finicky germaphobe (or just simply lucky), you may avoid the cold altogether. But more likely, that standard-issue runny nose and sore throat will show up roughly two to three times a year. The viruses that cause the cold live in your nasal passages almost constantly; when the body weakens, for one reason or another (the stress of cold weather is a common example), the virus can invade the body's cells, and all of a sudden the only recourse is to rush to the pharmacy two days later for a box of antihistamines.

The number of snot-nosed invalids wandering the streets every winter seems like a good enough reason to just cure the damn thing already! But there is at least one huge impediment: The U.S. health-care system is saving billions with the current system of over-the-counter (OTC) cough, cold and flu treatments.

According to a 2012 analysis of consumer spending, for each dollar spent on OTC medicine, the U.S. health-care system saves seven, with an estimated $102 billion saved annually. Cough, cold and flu medicines make up the largest share of OTC medical expense savings—about 28 percent or $28.6 billion annually.

If it weren't for the innumerable products designed specifically to treat symptoms caused by viruses that have no known cure, an estimated 56,000 additional medical practitioners would need to work full-time in order to keep up with the added burden of writing and filling prescriptions. Not to mention the added costs driven up by uninsured patients or those on Medicaid—pegged at an additional $4 billion per year.

But here's the thing: Even if there were 56,000 full-time doctors waiting on the sidelines, and cough/cold/flu medicines didn't make up the largest share of the OTC medicine pie, and uninsured and poor patients didn't add $4 billion to the health-care burden, pouring money into developing a cure would still be a waste of money. Why? According to Ann C. Palmenberg, biochemistry professor at the University of Madison-Wisconsin and former president of the American Society for Virology, the answer is Evolution—with a capital E.

"These viruses are very clever, obviously," Palmenberg told Newsweek. "They have a hundred million years of evolution adapting in the best possible way to make you uncomfortable and spread the virus."

With 200-plus viruses capable of causing the cold—and also able to mutate in a matter of days—scientists can't pick off the viruses one by one. Their only hope is to kill all the viruses simultaneously. But that would be the equivalent of tossing a hand grenade into a crowded room, just to kill a cockroach. It may accomplish its goal, but a well-placed spritz of Raid does the trick better. Scientists just haven't found their Raid yet.

The other challenge, as Palmenberg points out, is that "with the rhinovirus, you never feel so bad that you don't go to work and sneeze on your co-workers."

In other words, colds don't kill you. Instead, you feel just lousy enough that you need to down shots of crayon-colored syrup to stop feeling undead. In this case, OTC medicines work as the middleman. You benefit from the convenience of quick, though not altogether effective, relief. And the health-care system benefits from you not installing yourself in a hospital bed, allowing physicians to focus their attention on the patient whose thumb is awaiting reattachment.

That's for most cases. But not all colds are created equal. The average infant will contract six to 12 colds a year, and according to Palmenberg, for them, prescription medication isn't only superior; it could be life-saving.

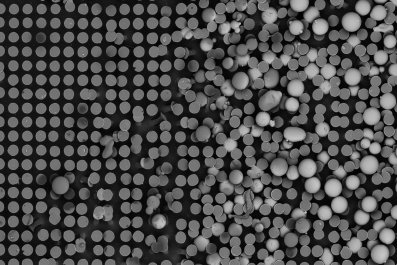

Palmenberg and her colleagues have been studying the so-called rhinovirus-C for years, most recently constructing a 3-D molecular model of the virus that has allowed the team to understand its pathology. What they found is that nearly all infant colds arise from this new, more potent form. Palmenberg believes her team will be able to use the model to develop "drugs that aren't over-the-counter, but by prescription, that will specifically target the [rhinovirus] Cs."

In the meantime, everyone else should get comfortable with the notion that the cold is here to stay. Like mosquitoes in the summertime or allergies in the spring, colds are pesky perennials.

In an age when heart disease is the number one cause of deaths worldwide and when life-threatening illnesses like cancer, stroke, dementia and diabetes still abound, the motivation for curing a virus that gives us the sniffles every now and then with a vaccine that could negate every prescription drug coursing through American bloodstreams, is a dangerously shortsighted one.

This race for a cure is one worth losing.